Ontario’s late-May labour law announcements, which include an increase in the minimum wage to $15 per hour, longer vacation time, and expanded leave policy, are a huge win for the province’s unions. At least, that’s the conventional wisdom. The president of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB), Dan Kelly, has said, “It is abundantly clear that from day one of this process, the government has focused their attention on furthering the interests of big unions.” And Jerry Dias, head of the largest private sector union, Unifor, called the moves “a bold first step to modernize Ontario’s employment laws.”

But, as economists often point out, there’s the short run and then there’s the long run. And in this case, a short-term win for the unions is likely to lead to losses for them in the long run. Those who consider independent labour unions a vital part of our economy and society (as I do) believe there is a good case to be made that these changes will have a deleterious effect on the long-term health of the labour movement.

Many, including the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, the CFIB and other business groups, point to the economic effect of increased labour regulation on labour markets and business vitality. These moves, they note, are only the latest of a series of changes that increase the costs to employers of hiring and maintaining a workforce. Whether it is increased certification requirements and costs associated with skilled trades or the financial cost of a mandated wage minimum wage increase or the shifting of more labour-related issues over to costly adjudication organizations like the Ontario Labour Relations Boardthe impact is likely to be a dampening of hiring and employment in some sectors and a slowdown of the economy as a whole. Others, such as John Manley, president of the Business Council of Canada, have noted that these changes will make Ontario firms less competitive in the global marketplace. A slower economy, these groups note, is bad for unions, because it will mean fewer workers that unions can bring into their folds.

Even if you are agnostic on this point or think the evidence points in another direction, the changes will ultimately be bad for unions. This is because the unions’ political influence increases the distance between unions and workers at the shop level, causing workers to see the state, not unions, as the primary advocate for the protection of their rights. And this is a disease, maybe even the death knell, for the labour movement.

Day by day, a union’s strength comes from the fact that individual workers see a union member, who they either elect or hire, representing them before their employer. That relationship — even in unions that don’t do a particularly good job of day-to-day representation — is a close one. Setting workplace rights and mitigating wrongs in workplaces through the collective agreement process is accomplished by a real person, who is associated with the union. You know your rep, and she wears the union colours. It’s low-level, shop-level justice; a voice for you in your workplace. And unions rightfully point to this voice as their advantage. Any union organizer will tell you — and the vast preponderance of data on why people join unions backs this up — it’s not just financial justice workers want. They also want a decent working relationship. The best way to achieve that is through a union representative you know and trust.

It is clear that what is happening here is a massive, union-supported, outsourcing of the unions’ workplace functions to the province.

With even a cursory glance at the announced changes in labour law and regulations, it is clear that what is happening here is a massive, union-supported, outsourcing of the unions’ workplace functions to the province. Take wages, for instance. The Ontario Federation of Labour boasts that unionized workers make, on average, $6.42 more than their nonunion counterparts. Now, some of that difference is because wages in certain industries (i.e., public sector, health care, and construction) skew that number a bit. Even allowing for that skewed number and applying it unevenly to lowest paid workers, the increase in Ontario’s minimum wage from $11.40 to $15.00 will eat up more than half of that union advantage.

The same principle applies to the mandating of paid leave for sick days, or equal pay for equal work. These are things that unions can rightfully take to nonunionized workers to induce them to join their union. The fact that these are mandated across the board through labour law diminishes that union advantage.

All of this is considered a feature, not a bug, by the unions who advocated for these changes. Why pour expense and effort into getting justice for the 114 workers at Fenelon Falls Long-Term Care Centre, when you can get justice for millions of workers in Ontario?

But utilitarian thinking is as bad for unions when it comes to labour law as it is for employers when it comes to human resources. There are two reasons for this.

When the union’s face is increasingly turned toward the state, which almost everyone experiences as a faceless thing, the worker is less likely to face in the same direction as the union.

First, while a lot of people point to unions’ strength in financial terms (they have piles of money from union dues), their real strength is the solidarity that comes from small groups of workers banding together to achieve justice. It is primarily sociological, not financial or political. It is easier to experience union strength as a worker when you see it in practice — first the union faces you, and then it turns around to face the employer. But when the union’s face is increasingly turned toward the state, which almost everyone experiences as a faceless thing, the worker is less likely to face in the same direction as the union. (Here’s a thought experiment: who is more likely to know what you take in your coffee: the labour ministry officer assigned to deal with your Employment Standards Act complaint or your union representative?)

Second, governments change. Groups that lobby for a given policy think that the government that gives them the laws will always be there. But the reality is that, even though it might take one, even two decades (okay, maybe three if you’re in Alberta), democratic governments eventually change. It is both necessary and important that unions be involved in politics for them to be able to properly represent their workers. But, through this involvement, unions spend more of the social capital they derive from solidarity than they generate. And when that capital is spent on laws that make the social-capital-generating toil in workplaces redundant, the union movement becomes brittle, more susceptible to the vagaries of politics in a democracy, and less resilient.

While certainly Ontario’s flirtation with right-to-work legislation proposed by Tim Hudak in 2012 was short lived, the province’s past experience, as well as the examples of right-to-work legislation in the US — in Wisconsin, under Scott Walker, and in Michigan — suggests that often the backlash has a way of sweeping away the political “wins” when unions focus their efforts on the legislature instead of on the worker at the lathe. When that happens, unions look back to the source of their power and find – just like the farmer who forgoes care for the soil in favour of a bag of fertilizer – that there’s nothing left.

When workers look to the state and not the union as the agent of justice, in the long run the very life-blood that provided the strength to achieve those laws will be eroded. A glance at union density numbers, and how unions are perceived (especially among youth) across the developed world, suggests that we are already well along this road. The latest changes in Ontario are likely to speed up these trends, not reverse them. Immediately after the Ontario government announced its labour law changes, the consensus was that the unions had won. My fear is that 10 years from now, the consensus might be that they actually lost.

This article is part of the The Changing Nature of Work special feature.

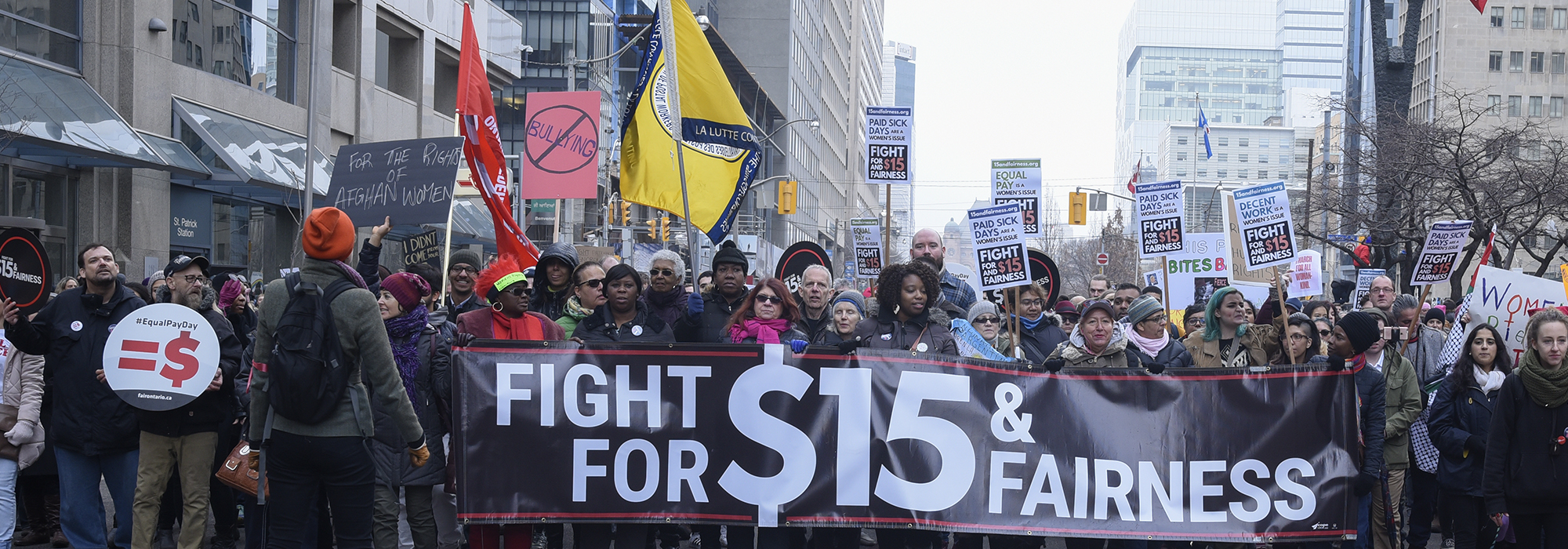

Photo: : TORONTO – JANUARY 21: A message to fight for $15 minimum wage being carried during the “Women’s March on Washington,” January 21, 2017. Shutterstock: arindambanerjee

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.