The realities of social assistance recipients are often misunderstood in Canada. As is the case for many social issues, this is primarily because access to data has long been limited. Yet without strong evidence, it is impossible to make evidence-informed policy decisions. With new data released by Maytree, we’re hoping this changes. Among the findings, we now know who is the most likely to receive social assistance, and how access to social assistance may have been impacted by the pandemic.

Maytree’s “Social Assistance Summaries” is an annual report that publishes data on the number of social assistance recipients. This year, for the first time, disaggregated data on household types and gender/sex from 11 jurisdictions has been collected and provided through the report. Disaggregated data, or data broken down into more detailed components, provides information on who is being affected by policy problems. It is an important and necessary tool that allows governments to implement more equitable, informed and thoughtful policy solutions.

We explore two of the most striking findings in the report. First, as it has been suspected for a long time, unattached singles are significantly overrepresented among social assistance recipients. Second, 2021 saw a decrease in the number of recipients in over three-quarters of social assistance programs across Canada. However, this is not because they were lifted out of poverty, but because they lost eligibility through pandemic supports.

Unattached singles are significantly overrepresented

Unattached working-age singles – adults without children or significant others – have consistently been the group most likely to live in poverty in Canada. In 2020, slightly more than 27 per cent of unattached singles lived below the official poverty line (market basket measure or MBM), compared to more than six per cent of the general population. This overrepresentation can also be seen in the number of people receiving social assistance.

As can be seen in Figure 1, unattached singles made up the majority (at over half) of social assistance recipients in 10 of the 20 social assistance programs across 11 jurisdictions. Furthermore, they were the largest group (but not the majority) in four programs, and they were the second largest group after single parents in six programs.

It is clear that working-age unattached singles comprise a significant proportion of social assistance recipients. It is also clear their income support levels continue to be highly inadequate relative to the government’s poverty measures.

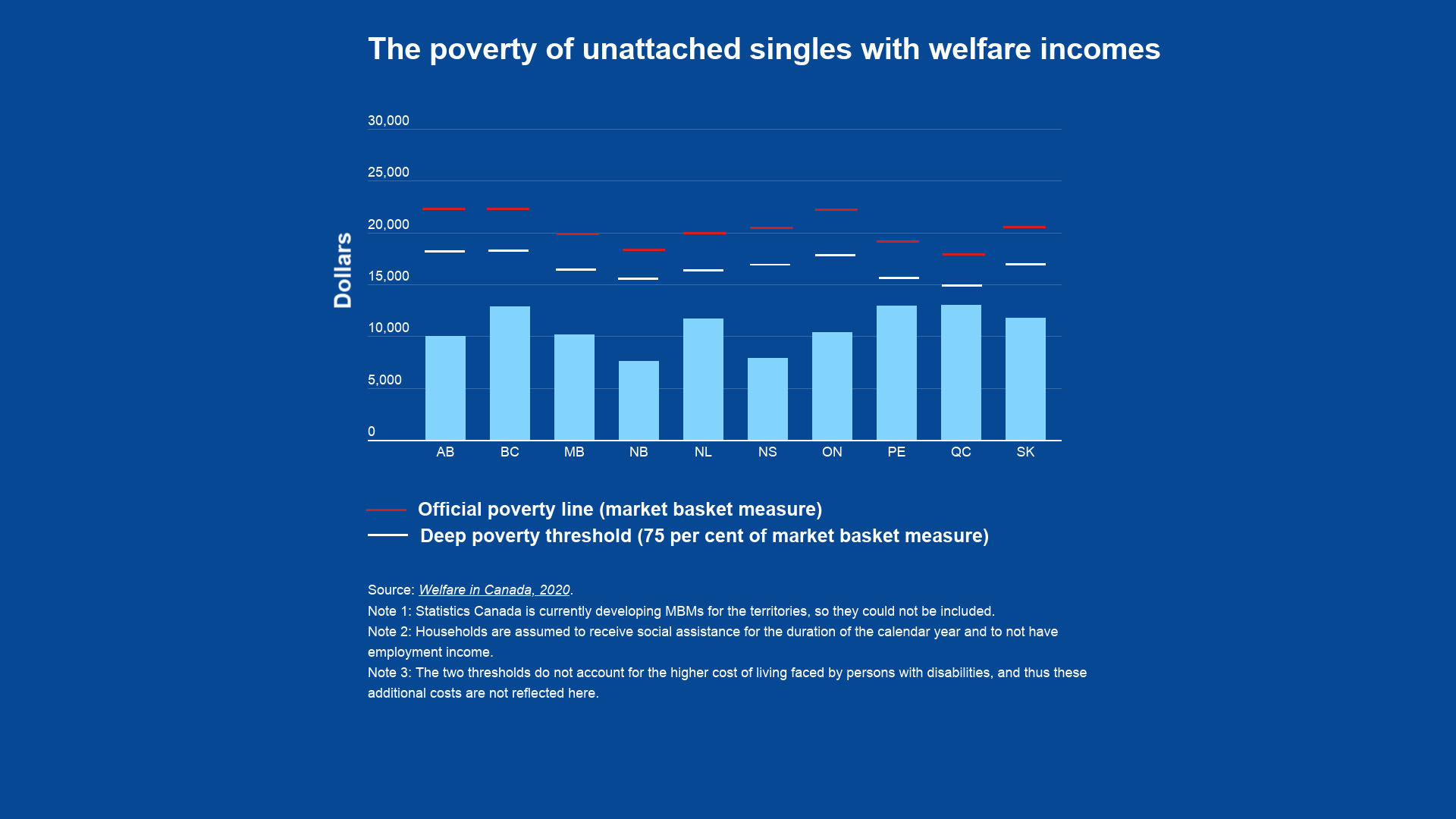

Figure 2 shows the adequacy of unattached singles’ welfare incomes relative to two thresholds: Canada’s official poverty line and the deep poverty threshold. Welfare incomes are a combination of social assistance benefits with federal, provincial and territorial refundable tax credits and benefits. In the figure, unattached singles are divided into two groups – “considered employable” and “with disabilities” – because each group receives different income supports.

As Figure 2 demonstrates, every unattached single household receiving social assistance lives below, if not far below, the deep poverty threshold, with two exceptions. In Newfoundland and Labrador, unattached singles with disabilities and in Alberta those receiving AISH (Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped) live above the deep poverty threshold. However, their welfare incomes are still below the official poverty line.

Unattached singles are the most likely household to receive social assistance, yet they also receive highly inadequate support. There is a clear disconnect here. Governments across Canada need to make good on their poverty reduction strategies by addressing the depth of poverty people experience and not only the rate of poverty. To achieve this, they will need to markedly increase their income supports for unattached singles in every jurisdiction.

Pandemic supports affected the number of people receiving social assistance

There are currently 21 social assistance programs in Canada. In 2021, 16 saw their number of recipients decrease. Only five programs in four jurisdictions saw their number of recipients increase in 2021.

At first glance, the decreases in the number of people receiving social assistance may be seen as a success story. Unfortunately, this is likely not the case. Instead, the drop reflects the unintended impact of emergency pandemic supports.

In particular, the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) was introduced at the beginning of the pandemic as an alternative to Employment Insurance (EI). EI did not have the capacity to provide the supports people needed at that time. One key difference between the two programs was that CERB had a lower employment hour threshold than EI and allowed many social assistance recipients who lost their employment to qualify for CERB, where they would not have qualified for EI.

The consequence was that CERB payments raised earned income of social assistance recipients above the earning thresholds of almost all social assistance programs, thus making them ineligible. For many, this meant accessing CERB resulted in losing access to social assistance benefits. The decisions on how much CERB benefits affected social assistance eligibility was in the purview of provincial and territorial governments.

Singles in deep poverty neglected by pandemic supports

A reform of taxes would make a Guaranteed Livable Income feasible

We need to start tracking the billions that go to social services

Podcast: Why isn’t social assistance improving health outcomes?

Some jurisdictions chose to reduce the impact of CERB. British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and Yukon fully exempted CERB payments, meaning people did not lose their social assistance benefits. Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec partially exempted the CERB benefits, meaning benefits from CERB were taken into account when calculating benefit levels for social assistance. However, even partial CERB payments were still above the earning thresholds for all programs except AISH in Alberta and the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP).

As can be seen in Figure 3, the interaction between CERB payments and social assistance eligibility clearly had an impact. Exemptions in British Columbia and partial exemptions for Alberta’s AISH and Ontario’s ODSP limited the impact of CERB on their number of social assistance recipients.

The loss of a key benefit was also experienced by seniors who lost access to the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) after receiving CERB payments. Nevertheless, the federal government was proactive. Seniors were given a one-time payment as compensation demonstrating the federal government’s capabilities to correct some of the unintended consequences of CERB. This can and should be done for social assistance recipients, with the collaboration of provincial and territorial governments.

Takeaways

The newly released Social Assistance Summaries data is incontrovertible. Unattached singles are the most likely recipients of social assistance across Canada. Yet, the income support they receive is inadequate, forcing many to live in precarity and deep poverty. Governments must take steps to reduce the depth of poverty that they face by increasing their income supports.

Furthermore, the report shows that the decrease in the number of social assistance recipients masks a loss of support for some of the most vulnerable people in Canada. Governments must also recognize the inadvertent impact of CERB on social assistance recipients and, as they have done in the case of seniors, address any loss in benefits.

The data in Social Assistance Summaries helps develop the resources required to make good, evidence-based policy decisions. It is time that governments use this data to take policy action and begin to guarantee that people living in deep poverty can live a life with dignity.