In 2020, the federal government spent over $160 billion on COVID-19 pandemic response measures. These expenses were critical in supporting recently unemployed workers and affected businesses in a time of uncertainty. However, supports through programs like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) were not extended to those who had less attachment to the labour market, such as a large proportion of social assistance recipients.

This pattern of exclusion has continued with the more recent Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit, which was created to support workers affected by new pandemic-related shutdowns, and not people who were already living in deep poverty before the pandemic.

The pandemic benefits are intended to support people during a specific time of crisis — but what about those who have been living with low and insecure incomes for decades?

Maytree’s latest edition of the Welfare in Canada report, which looks at the welfare incomes of people receiving social assistance in each province and territory over the 2020 calendar year, focuses particularly on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic supports on welfare incomes. The results are worrying. After years of developing this report, we see the same pattern: across Canada, people who receive social assistance have very low incomes and face deep levels of poverty.

How adequate are welfare incomes?

In the report, we analyze the welfare incomes of 53 example households, divided into four types. Here, we will focus on unattached singles considered employable (figure 1), as they are the most likely to be living in poverty.

Figure 1 shows how inadequate welfare incomes are. Every unattached single household receiving social assistance in all 10 provinces was not only living in poverty but living in deep poverty. In most provinces, the gap between total income and the deep income poverty threshold is significant, even with some additional pandemic supports. Most notably, the welfare incomes in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick would have to be more than doubled to reach the deep income poverty threshold and tripled to reach the official poverty line, which corresponds to the market basket measure (see Figure 1).

How much additional support was provided?

Every household examined in the report received at least some additional COVID-19 pandemic-related support from the federal government (figure 2).

Several households also received pandemic-related supports from their provincial or territorial governments. Four provinces (British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan) and one territory (the Northwest Territories) provided these supports. Similar supports were also available in Ontario, but only for those who knew to apply, and most social assistance recipients didn’t receive them. No additional supports were available in the other five provinces and two territories.

The federal pandemic-related supports came exclusively from a one-time increase to the GST/HST tax credit, which amounted to $290 (except for the Northwest Territories and Yukon, where it was slightly higher). This resulted in increases to welfare incomes of between one and four per cent. It is worth highlighting that this top-up was not specific to social assistance recipients but was generally available to everyone receiving the credit. For households with children, the federal government also provided a one-time increase to the Canada Child Benefit.

The five sub-national jurisdictions that provided COVID-19 supports did so in a more targeted way, almost exclusively distributing them through their social assistance programs. British Columbia is by far the standout, offering unattached singles $2,875 in 2020. The Northwest Territories provided $675. Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan offered more modest top-ups between $50 and $100.

What was the impact of these supports?

While pandemic-related supports were meager, they undoubtedly provided a much-needed boost to otherwise stagnating and inadequate welfare incomes. In fact, a surprising finding from our analysis was that between 2019 and 2020, all households in all provinces and territories received income increases amounting to more than the rate of inflation. In most cases, the majority of those increases came from these short-term pandemic-related supports.

Figure 3 shows the percentage increases in total welfare income for unattached singles in each province and territory between 2019 and 2020, highlighting the proportion that came from pandemic-related supports.

In eight of the 13 jurisdictions, the majority of the increases in welfare incomes came from pandemic-related supports. In British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nunavut, over 95 per cent of the increases in welfare income came from pandemic related supports.

In Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan, notable increases were made to non-pandemic related social assistance benefits, which contributed more toward year-over-year welfare income growth than pandemic related supports for unattached singles in 2020.

How does it compare to CERB?

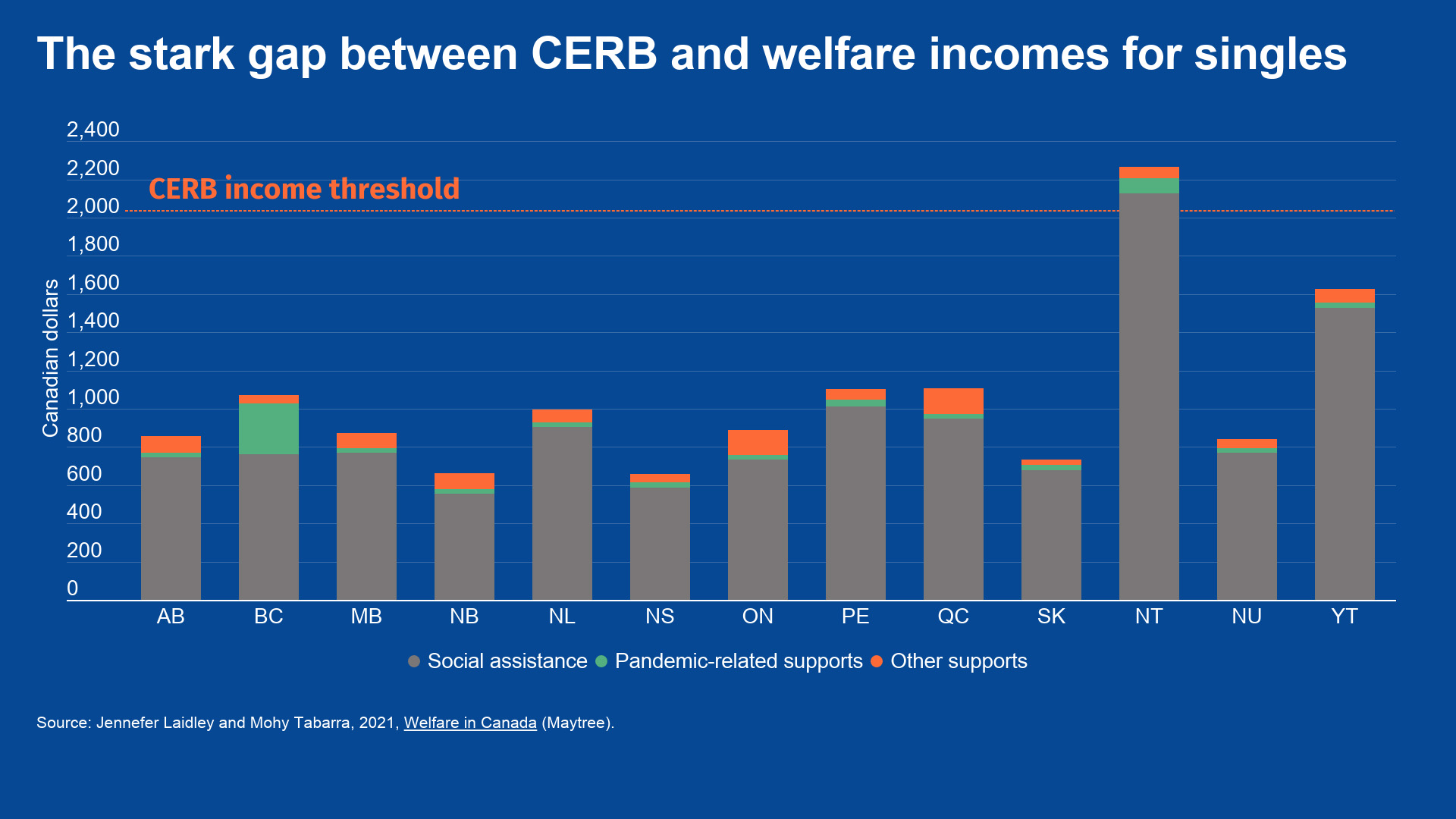

CERB was a federal program that provided $2,000 per month from March to September 2020 to any adult who had recently lost their job due to shutdowns related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and who earned an income of at least $5,000 in the last 12 months or in 2019. CERB was a short-term substitute for an EI system that was overwhelmed by the large number of recently unemployed people. The majority of people receiving social assistance did not qualify for CERB, however, because they did not earn a sufficient income or were too removed from the labour market. Nonetheless, it is helpful to compare welfare incomes to CERB because it shaped what we — the general public and governments — might think is adequate in a time of crisis (figure 4).

As figure 4 shows, the monthly welfare income of unattached singles was below, if not well-below, the CERB in 12 of the 13 jurisdictions. What’s more, pandemic-related benefits provided to unattached singles receiving social assistance were just a sliver compared to the much more generous amounts received by those who were more recently employed. Even in British Columbia, which had by far the most generous COVID-19 benefits, the $2,850 in additional support is less than a month and a half of CERB. The Northwest Territories is the exception as total welfare income was higher than CERB, but it’s important to highlight the significantly higher cost of living in the territories.

Even if we compare these welfare incomes to the more modest $300 a week of the more recent Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit (about $1,200 a month for those who qualify), all 10 provinces and Nunavut would fall below that amount.

What happens when pandemic supports end?

While nowhere near sufficient, pandemic supports reduced the depth of poverty of those most vulnerable in Canada at a critical time. These supports were mostly one-time additions to income, however, which means that by now the households have already lost these gains. Combined with high inflation in 2021 (3.4 per cent), the loss of these additional supports means that their level of poverty will deepen going forward.

Governments have shown that they can rise to the occasion and provide people with adequate income support during an emergency. For those receiving social assistance and living in deep poverty, the emergency is relentless and every day. Given how the pandemic has underscored inequities that exist in our society, governments must step up and ensure a life with dignity for those in greatest need.

As a reference report, Welfare in Canada doesn’t propose specific policy solutions. But the data and analysis suggest that governments across Canada should:

- consider the creation of a stackable benefit that meaningfully reduces the depth of poverty of unattached, single, working-age adults;

- ensure the federal government’s proposed Canada Disability Benefit is implemented;

- boost social assistance rates;

- and increase federal spending in achieving poverty reduction targets through enhancement of the Canada Social Transfer.

We shouldn’t be okay with the status quo. After years of underinvestment, even during a pandemic, it’s time that we permanently increase social assistance levels so that they are much more adequate, and ensure that people in deep poverty can live with dignity. In the meantime, governments should provide targeted additional supports to people in deep poverty at a time of crisis just as they have for the recently unemployed.