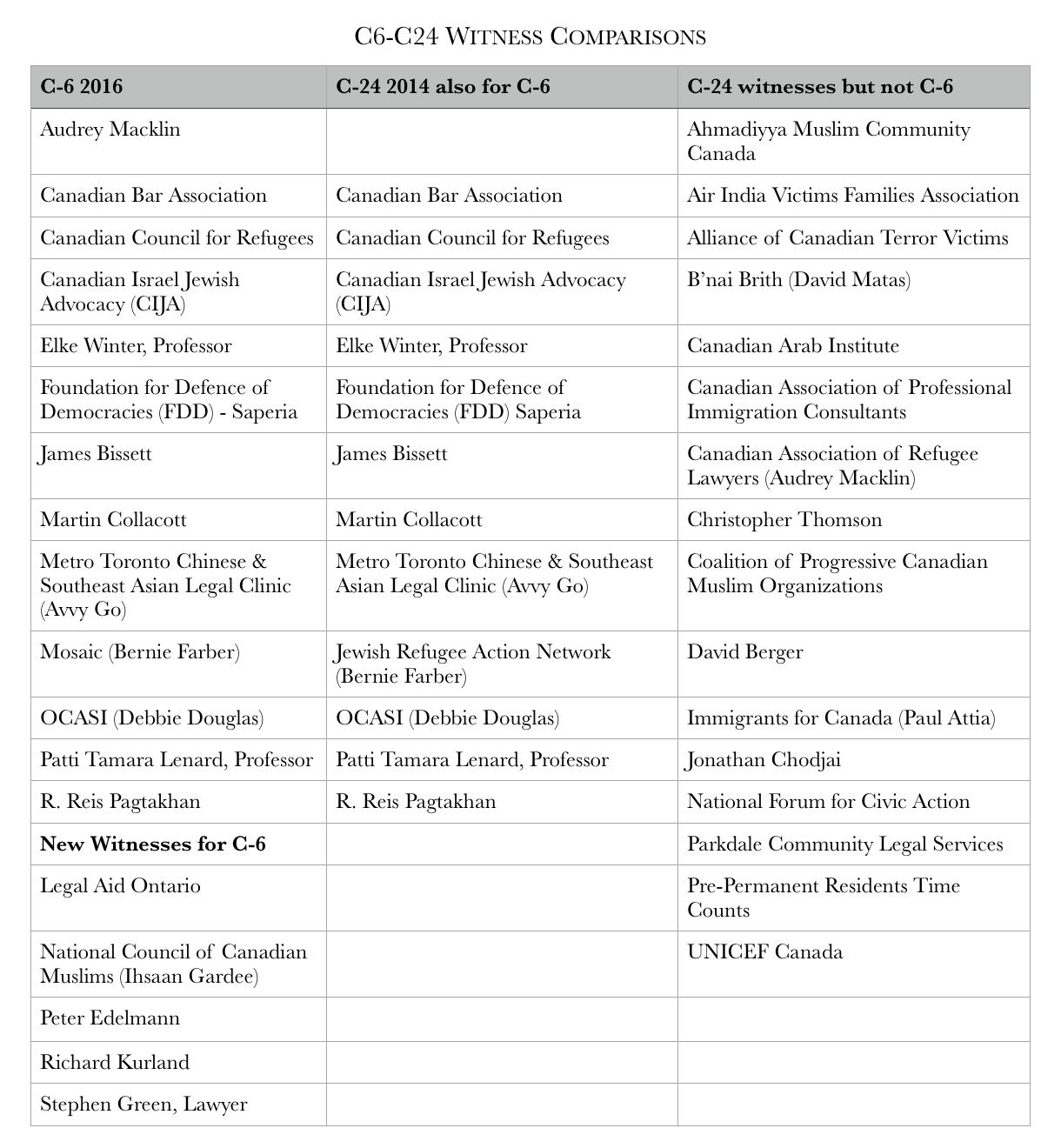

A Commons committee has finished hearing witnesses on the proposed changes to the Citizenship Act in Bill C-6, and is proceeding to clause-by-clause examination of the legislation. Contrasting the nature of the committee testimony with that of Bill C-24, the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act, some two-years ago reveals similarities and differences. A number of suggestions were broadly in line with the government’s overall agenda of diversity and inclusion, and it will be interesting if the government responds to these in amendments to the bill.

Starting with the common elements between the two sets of hearings:

- An almost complete absence of Quebec-based witnesses and French-speaking witnesses, and thus any Quebec-specific citizenship issues that may reflect its different mix of source countries, particularly from the Maghreb, where revocation, or removal of citizenship, would likely be a particular concern;

- An almost complete lack of statistical data with witnesses talking either in conceptual terms, anecdotal examples, or principles, without any reference to the numbers of people potentially affected by the changes. Assertions by those impacted, for better or worse, by the previous or current Bill, would benefit from the hard numbers;

- Both sets of hearings ensured different perspectives.

However, a number of significant differences between the study of the two bills, reflecting the change in government, are also notable:

- 18 witnesses for C-6 compared to 28 for C-24, reflecting the broader scope of C-24 and a likely tighter timeline under the current government;

- About 40 percent of witnesses broadly supported the revocation of citizenship provision during the study of the Conservative government’s C-24, in contrast to about 25 percent during the study of C-6, reflecting the previous administration having ensured a majority of witnesses in support of the most controversial change;

- A generally more open tone in discussion and the questioning of witnesses by all parties. The witnesses for the most part recognized that a change in government meant a needed change in tone and approach. Shimon Fogal of the Canadian Israel Jewish Advocacy exemplified this approach, going out of his way to recognize the arguments against revocation while maintaining his position in favour of it. James Bissett and Martin Collacott, both former public servants with immigration experience, did not, thus undermining their arguments as they largely repeated their arguments and their tone from previous testimony.

- Predictably, witnesses that favour an easier pathway to citizenship, while welcoming the proposed changes of C-6, focused on what they perceived as remaining gaps: procedural protections for revocation of citizenship in cases of fraud or misrepresentation; barriers to refugees and some immigrants with respect to more difficult knowledge test and language assessments; the need for exceptions to the requirement of physical presence in Canada and not merely the possession of a legal address; and the high cost of citizenship fees ($630) and language assessments (about $200) for all applicants.

Minister McCallum did express some openness to amendments and the nature of the questions from Liberal MPs suggested the same flexibility. While the extent of this willingness is unclear, the following is my take on possible amendments, based on their broad consistency with the government’s “diversity and inclusion agenda” and the principles and philosophy behind Bill C-6:

- Revocation for fraud or misrepresentation: C-24 removed the rights or «procedural protections » that those facing revocation faced, including recourse to the Federal Court, leaving revocation at the discretion of the Minister and delegated officials. There was broad support to ensure those protections were made comparable to those in place for revocation of permanent residency, which provides for an oral hearing. Some argued for reverting back to the former process requiring a Federal Court ruling, which was lengthy. Others argued for the Immigration Review Board (IRB) to expand its mandate to include citizenship hearings, which would require additional resources.

- Language and knowledge testing: The government responded to public pressure by reverting to the previous age range of 18 to 54 for the testing, but did not (wisely in my opinion), allow the knowledge test to be taken with an interpreter. The revision of the study guide, Discover Canada, and the related citizenship test questions, will presumably (and should) include a complete rewrite into plain language. This would address many but not all of the issues raised by witnesses, without a further weakening of the language requirements, with language skills so important to integration.

- Physical presence requirement: This provides a clear and common sense definition of residency. However, given the nature of a more mobile and global world, particularly for many economic immigrants, there is a strong case for some forms of defined exemptions. These exemptions could include those who work for a Canadian company abroad, or leave the country for health and compassionate grounds. Or the exemptions could revert to the previous, broader guidance provided to citizenship judges.

- Citizenship fees: While not part of legislation, the quintupling of fees in 2014-15 and the additional cost of up-front language testing will reduce the number applying, and thus reduce the naturalization rate, a trend we are already seeing. Fees are a significant barrier for lower income immigrants and refugees. Given that a large part of Canada’s relative success as a diverse society reflects a clear pathway to citizenship, addressing the cost, through a general reduction to perhaps $300, possibly combined with a partial waiver for refugees, would help restore this pathway to citizenship and political integration.

Whether the government will consider amendments, or whether the selection of witnesses was part of a strategy to allow the government to demonstrate flexibility, will tell us both about the specific citizenship policy directions as well as their general approach to governing. Will they view Parliament only as a way to deliver on their political commitments, or will they view Parliament as a significant forum for more open policy discussions, debates and decisions?

The upcoming clause-by-clause review starting May 3rd will illustrate their approach in both the particulars of C-6 as well as the broader context.

Photo: Art Babych / Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.