Contemporary production processes involve various complex tasks including: product design, assembly, distribution and marketing. In a global value chain (GVC), these activities are performed across international borders to take advantage of efficiencies in different locations.

The scope and speed with which worldwide production has integrated into GVCs has generated interest into their effects on productivity. A growing theoretical and empirical literature is finding that a country’s integration into GVCs can improve its productivity performance. This contribution of this new chapter in the IRPP’s trade volume, written by John Baldwin and Beiling Yan of Statistics Canada, is to examine how GVC participation impacts productivity at the firm level.

The authors use detailed data for over 30,000 Canadian manufacturing firms between 2002 and 2006. They define a GVC participant as a firm that imports intermediate goods and exports either intermediates or final goods, and they investigate what happens over time to the productivity performance of firms that enter and exit a GVC.

Some takeaways

This chapter is important because it helps move the conversation beyond a typical positive correlation between trade and productivity towards a more causal interpretation. Although it’s true that firms with superior performance are more likely to participate in GVCs, it’s also the case that becoming part of a GVC improves firm performance — and similarly that quitting a GVC hurts firm performance. Put differently, ‘better’ firms join GVCs, and joining GVCs makes firms better; ‘worse’ firms avoid GVCs, and quitting them worsens performance.

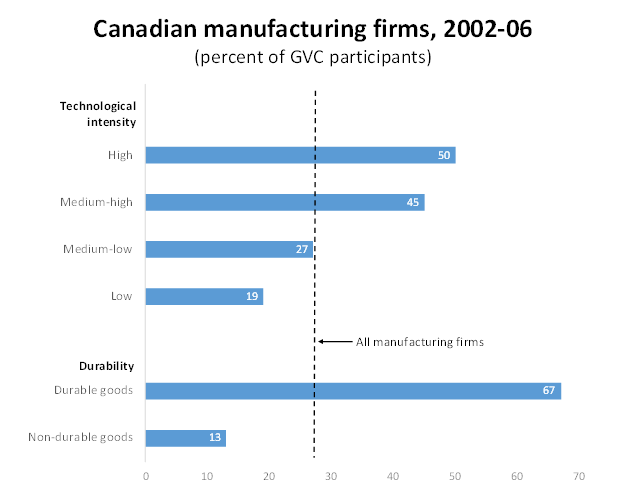

Moreover, while the results show that GVCs are more prevalent in higher-technology manufacturing industries, their productivity-enhancing effects are found across many sectors.

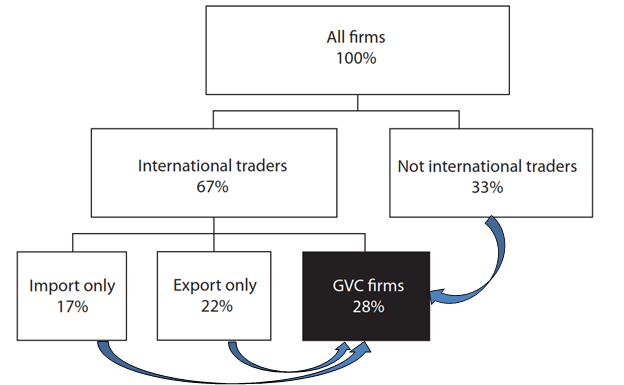

This chapter also carefully documents how Canadian firms enter and exit GVCs, and disentangles the contributions made by exporting versus importing. It finds that exporting is generally the more active channel (that is, GVC entry comes primarily from importers that start exporting, while GVC exit comes largely from two-way traders that stop exporting). In addition, the productivity benefits from exporting are larger and longer-lasting than the positive effect from importing.

These findings have some potentially-important policy implications. A trend observed over the past 15 years — and a recent area of policy focus — has been to increase the share of Canada’s exports to emerging markets. This research suggests that we might expect smaller productivity gains from increasing Canadian exports to emerging markets (relative to trade with other advanced economies) and a more immediate productivity loss if those trading relationships eventually sever.

Some key findings

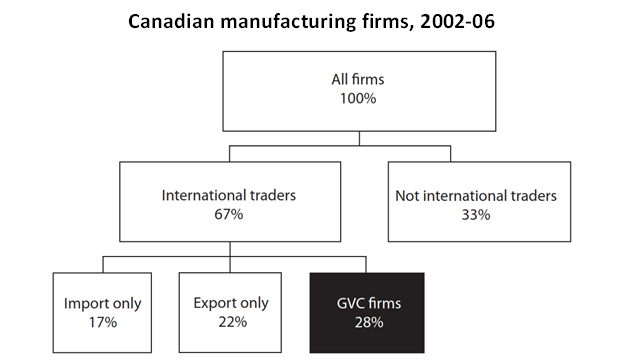

1. On average over the 2002-06 period, two-way trading GVC firms accounted for less than a third (28%) of the firms in their sample.

Despite their small population share, GVC firms were responsible for most of the value of international trade in Canada’s manufacturing sector: 90% of all intermediate imports and 83% of exports (the rest came from those who only imported or only exported).

Despite their small population share, GVC firms were responsible for most of the value of international trade in Canada’s manufacturing sector: 90% of all intermediate imports and 83% of exports (the rest came from those who only imported or only exported).

2. GVC participation rates were highest in high-tech and durables industries:

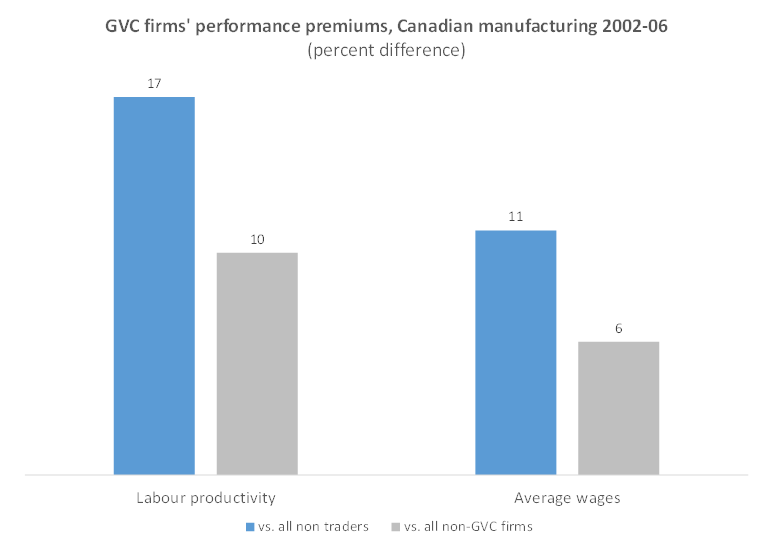

3. Consistent with recent firm-level trade theory, GVC firms performed better than other firms (after controlling for year and industry fixed effects and for firm size). GVC firms had more employees, were more productive, paid higher average wages, and were more likely to be foreign-controlled. The performance gaps were largest when comparing GVC firms with non-traders (whereas the non-GVC group includes one-way traders):

3. Consistent with recent firm-level trade theory, GVC firms performed better than other firms (after controlling for year and industry fixed effects and for firm size). GVC firms had more employees, were more productive, paid higher average wages, and were more likely to be foreign-controlled. The performance gaps were largest when comparing GVC firms with non-traders (whereas the non-GVC group includes one-way traders):

4. Do these performance gaps simply reflect the tendency for ‘better firms’ to join GVCs (positive self-selection) or does the act of two-way trading actually makes firms ‘better’ (controlling for other characteristics)?

4. Do these performance gaps simply reflect the tendency for ‘better firms’ to join GVCs (positive self-selection) or does the act of two-way trading actually makes firms ‘better’ (controlling for other characteristics)?

To disentangle these effects, the authors compared groups of firms who differed by those that joined GVCs (the treatment group[1]), and those that didn’t (control group).

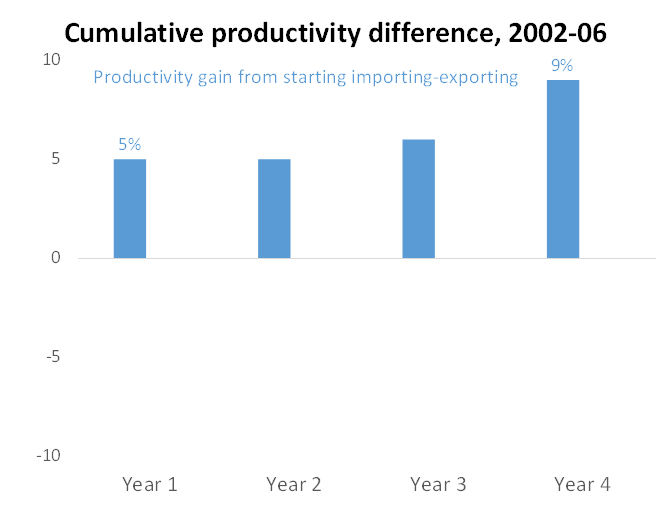

After controlling for selection effects, they find that GVC starters became more productive:

After controlling for selection effects, they find that GVC starters became more productive:

During their first year, these firms experienced 5% more productivity growth, and this advantage accumulated to 9% after four years.

During their first year, these firms experienced 5% more productivity growth, and this advantage accumulated to 9% after four years.

Interestingly, the largest gains came from those firms in Canada that started to export to other advanced economies. This is consistent with the “learning by exporting” story and technology transfer. These gains also seem to be more persistent.

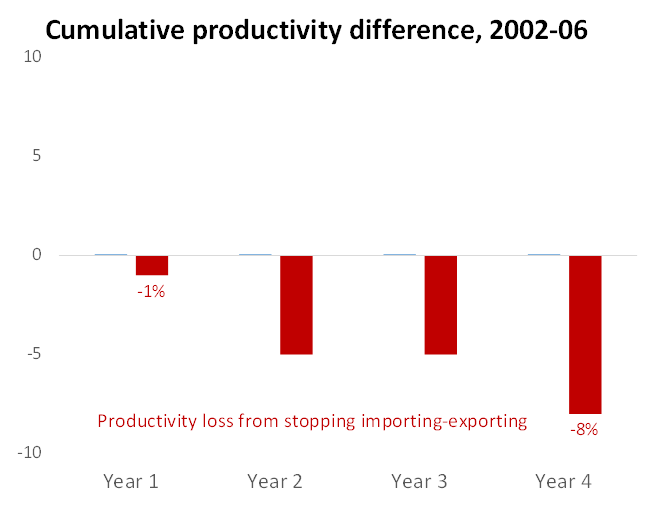

Conversely, firms that quit GVCs did worse than continuing GVC firms. Over time, the productivity losses for quitters were similar in size to the gains from joining GVCs.

The largest and most immediate losses for GVC quitters were found for Canadian firms that stopped importing from developing economies. This is consistent with forgoing cost savings from importing or offshoring part of their production processes.

The largest and most immediate losses for GVC quitters were found for Canadian firms that stopped importing from developing economies. This is consistent with forgoing cost savings from importing or offshoring part of their production processes.

I highly recommend reading the full chapter here.

******

[1] The treatment group includes the non-traders, and one-way traders, who became two-way traders. Similarly the authors also compared GVC quitters to those that continued — in both cases, using propensity score matching and difference-in-difference regression techniques.