Just how diverse is the federal public service? This question recently has attracted more scrutiny, particularly when it comes to the inclusion of Black Canadians in the bureaucracy. Before February, no Black person had made it to the deputy minister rank of the public service – Caroline Xavier is now associate deputy minister of immigration, refugees and citizenship. The speech from the throne included a commitment to “Implementing an action plan to increase representation in hiring and appointments, and leadership development within the public service.”

Now, for the first time, the federal government is providing disaggregated data related to the diversity of the public service as part of its Employment Equity Report. The Treasury Board Secretariat’s (TBS) report looks at the three fiscal years from 2016-19 by occupational group. Previously, disaggregated data for visible minority and Indigenous individuals employed in federal public administration (excluding the military) was only available through census data every five years. We now have the tools to do a more granular analysis of visible minority representation in each occupational group and see where work remains to be done.

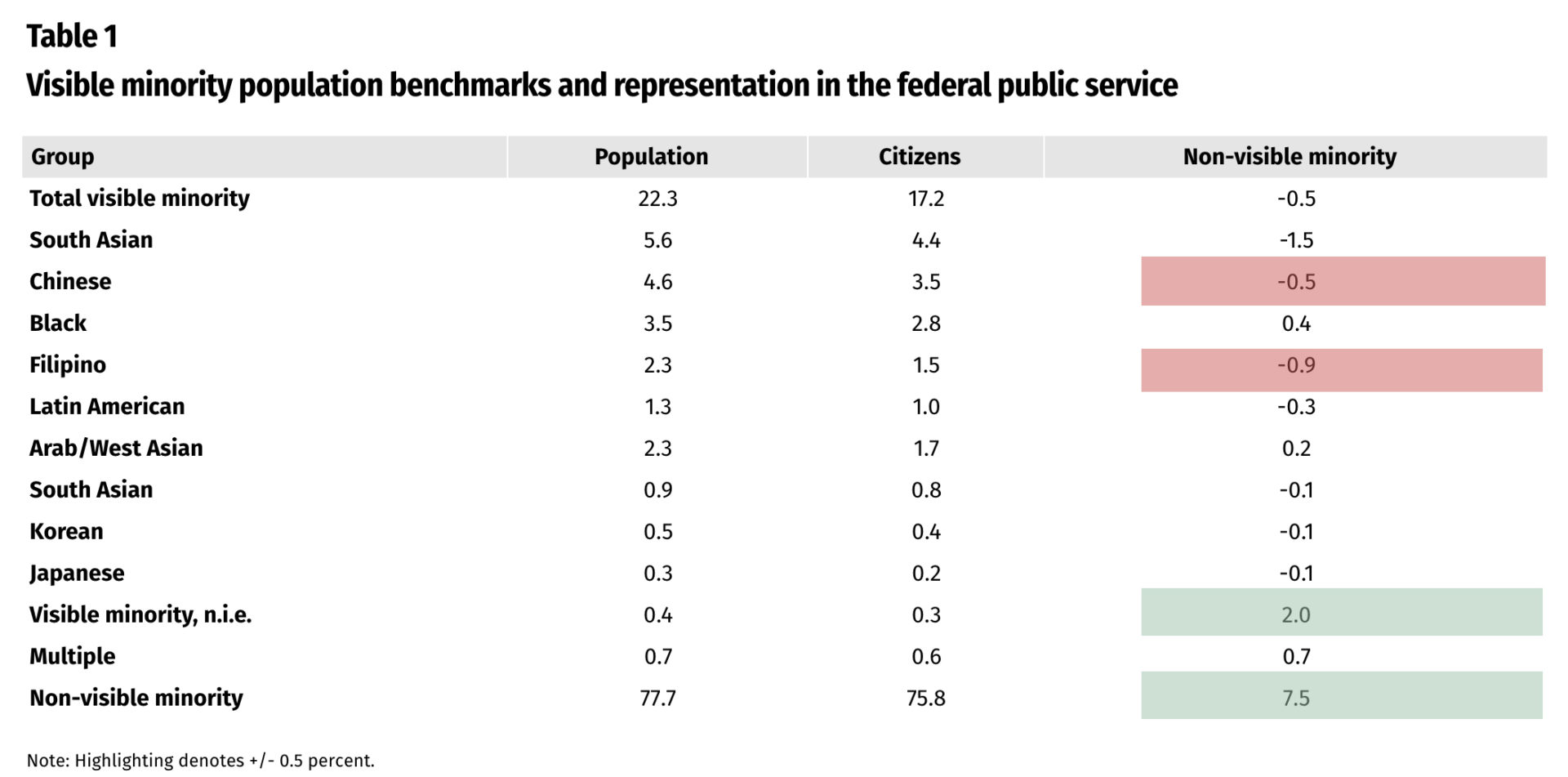

Table 1 looks at the overall visible minority representation in Canada, the visible minority population that are citizens, and the numbers shared in the government’s equity report. The citizenship number is taken here as a benchmark, since citizens are given preference in government staffing processes. This gives us a picture of the degree to which there is under-representation of certain groups compared to the citizenship-based benchmark.

A note about the terminology: I have used the term visible minority, as do Statistics Canada and the Treasury Board Secretariat. Indigenous Peoples are their own category for data purposes, and do not fall under visible minority. While the visible minority group definitions are similar to those used by Statistics Canada, TBS groups Arab and West Asians together under “non-white West Asian, North African or Arab.” “Mixed Origin” refers to those with one visible minority parent.

The representation of most groups is relatively close to their share of the citizenship population, with South Asian, Chinese and Filipino public servants less represented.

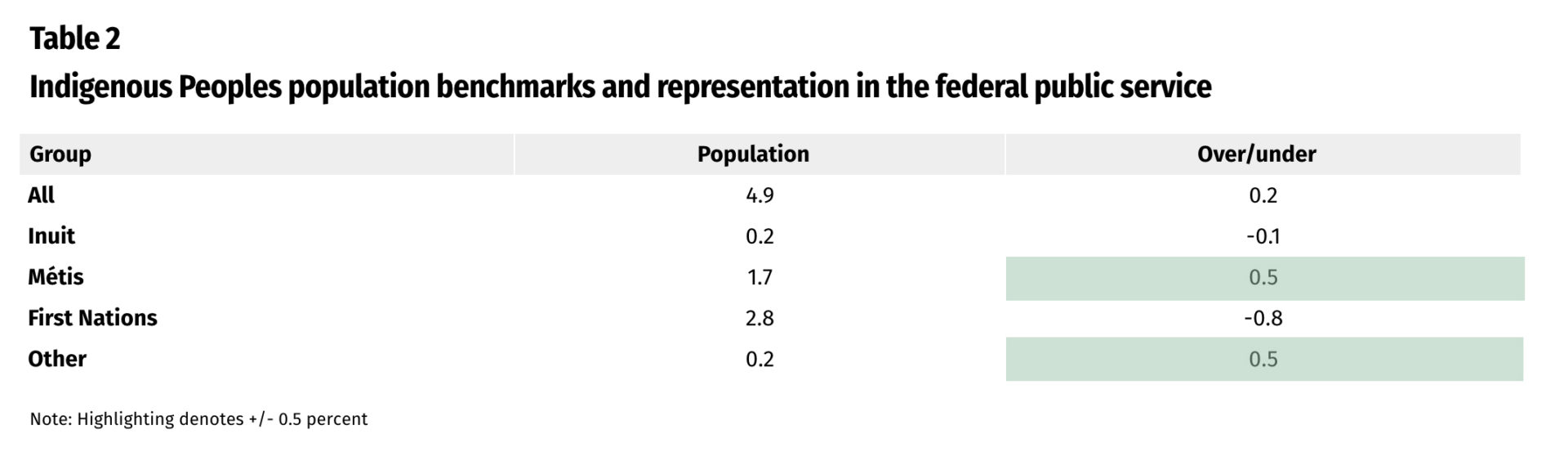

Table 2 takes the same approach with respect to Indigenous representation with the exception that total and citizenship-based populations are identical, showing relative under-representation of First Nations and Inuit people.

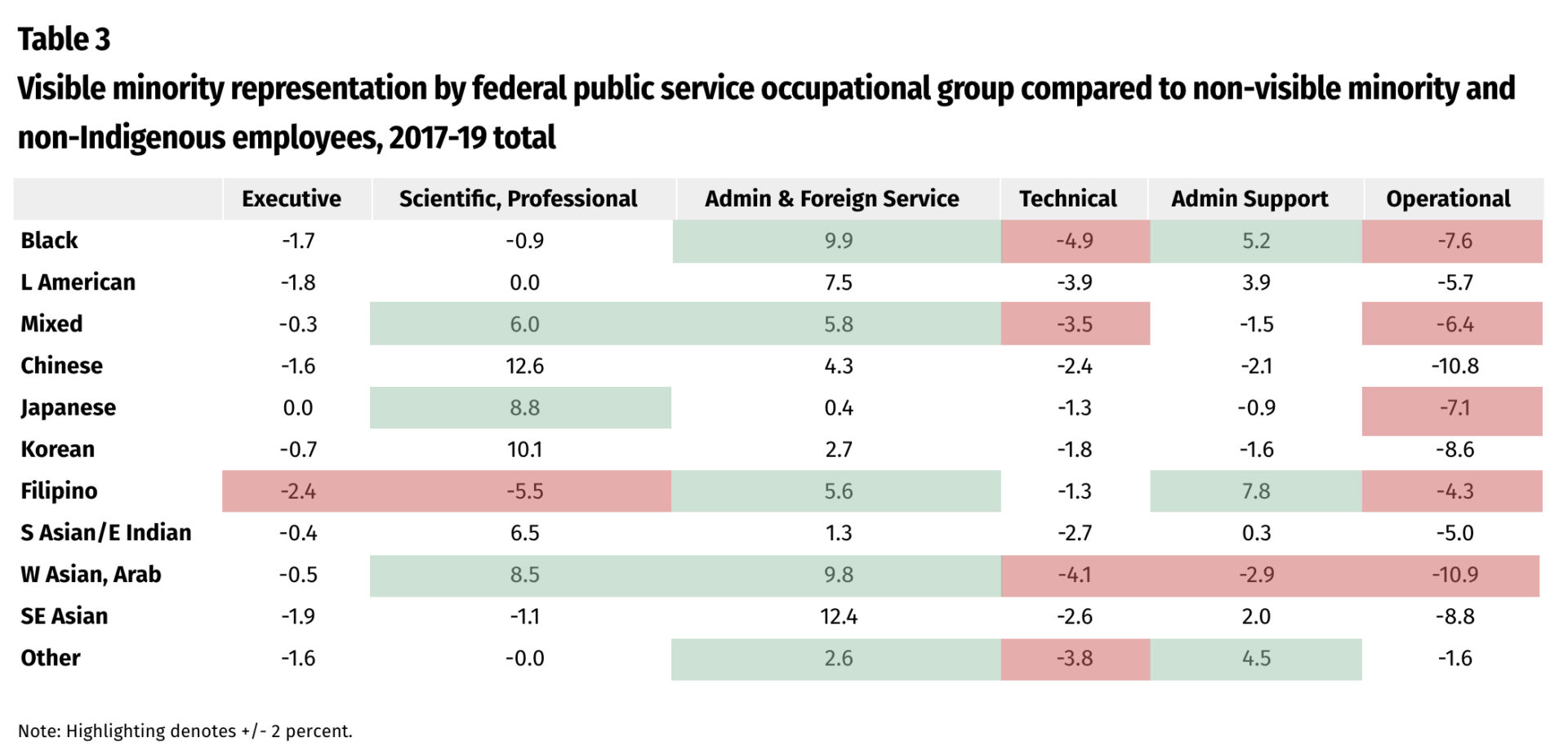

Table 3 compares the representation of each visible minority by occupational group, expressed as the percentage difference with non-visible minority, non-Indigenous employees for the three-year period 2017-19. For most groups, relative representation has not shifted dramatically from 2017 to 2019, with general under-representation in the executive, technical and operational categories.

Among executives, no group has improved its representation by one percent or more from 2017 to 2019, with only individuals of mixed origins showing an increase of 0.6 percent, and Black, Filipino and Southeast Asian people showing marginal increases (0.1, 0.3 and 0.1 percent respectively).

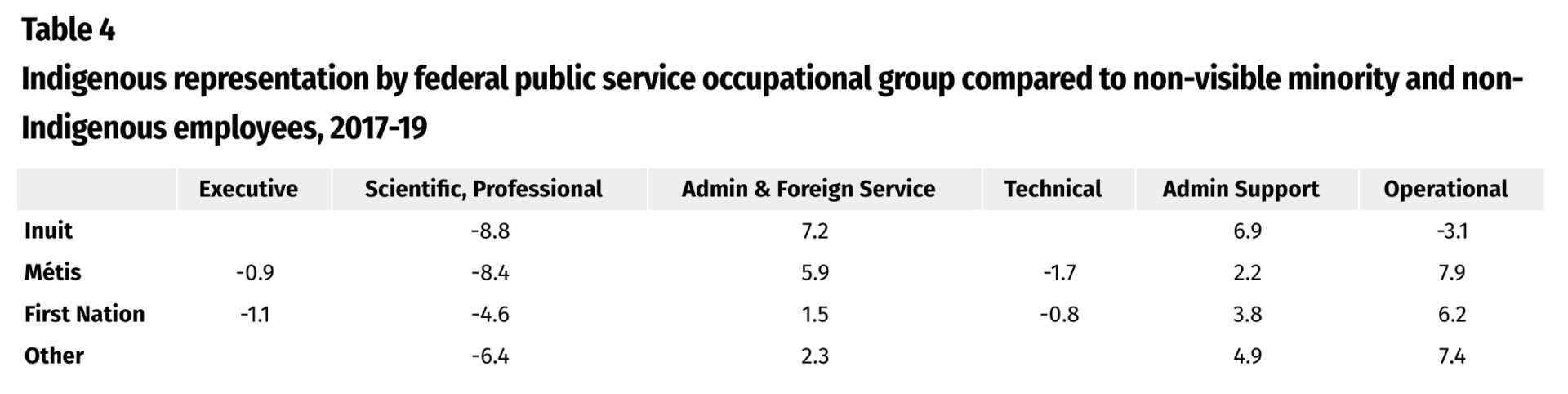

Table 4 similarly compares the representation of each Indigenous group by occupational groups, expressed as the percentage difference with non-visible minority, non-Indigenous employees for the three-year period 2017-19 (for the executive and technical occupational groups, there are fewer than five Inuit public servants, and thus the federal government does not provide numbers out of concern for privacy).

While this analysis highlights the differences in visible minority and Indigenous representation among the different occupational categories, it does not break it down by seniority level.

TBS declined to provide a disaggregated breakdown for assistant deputy ministers (level EX4-5) and directors and directors general (level EX1-3) given that breaking down the numbers to those subgroups would present a privacy risk. But TBS did say that of the 335 ADMs, 30 are visible minority (9.0 percent) and nine Indigenous (2.7 percent).

Black Canadians are the visible minority group with the strongest numbers in the public service compared to their share of the citizen population, but their representation is overwhelmingly in the two administrative categories. This is not unique – there is significant under-representation among Latin American, Chinese, Filipino and South East Asian groups in the executive ranks of the public service. A similar general pattern can be found with Indigenous public service representation.

With this type of disaggregated data in hand, policy discussions and responses can be based more solidly on evidence rather than relying on examples and anecdotes about who works in the public service. With better data, the government can hopefully build a more representative and inclusive public service at all levels.

Photo: Shutterstock/By elenabsl