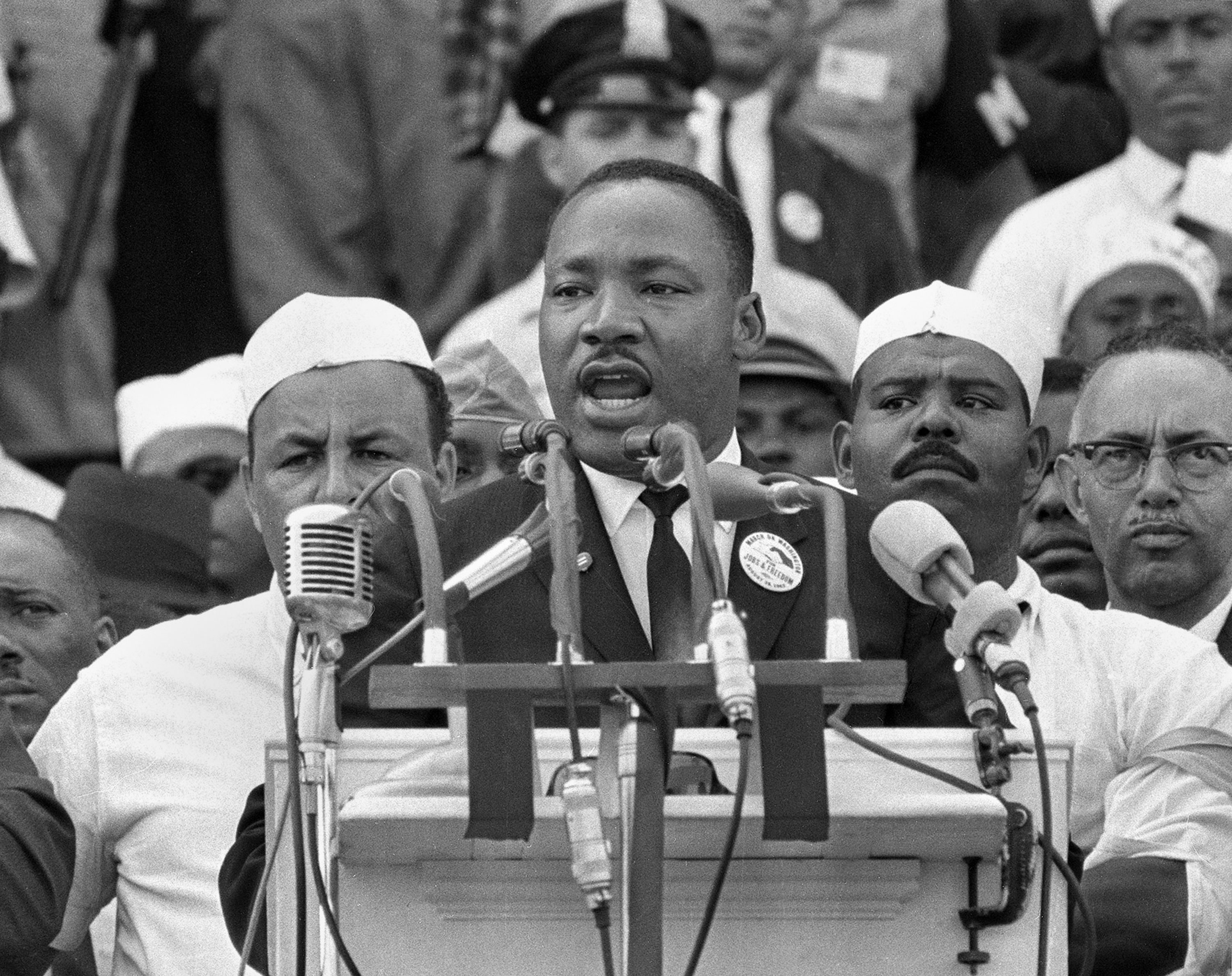

Measures in Budget 2018 meant to address racism and promote social inclusion appear to have inspired moral panic in the Twittersphere. Commentators, including Conservative MP Maxime Bernier, express anguish that the government’s decision to target funding to racialized communities is unjust and divisive. Bernier invoked no less a figure than Martin Luther King Jr. to chastise those who support such actions. But the King they invoke is an illusion — far removed from the iconic civil rights activist who demonstrated an unrelenting commitment to equality and the eradication of racism.

The true spiritual call to arms of King’s entire “I Have a Dream” speech appears to have been lost on some. Instead, his aspiration that his children might mature in a world free of racism is advanced as the sole message of value. But those who would invoke King must respect the integrity of his work. They must demonstrate that they truly seek to be judged not by their whiteness or the colour of their skin but by “the content of their character.” They must move beyond platitudes to action. They must have the moral courage to acknowledge the need for redress for years of marginalization and systemic anti-Black racism.

This controversy over the use of the term “racialized” demonstrates the continuing relevance of all of King’s speech to contemporary race politics in Canada. King called for acknowledgement that the “manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination” were crippling the life chances of Black people. In the spirit of King, the announced commitment of $19 million to support Black youth at risk and to research mental health programs may bring about greater justice for Black people.

Almost 20 years ago, in 1999, I served as the co-chair of the Canadian Bar Association Working Group on Racial Equality. I penned a complementary report, entitled Virtual Justice: Systemic Racism in the Canadian Legal Profession. I spoke of racialized communities and rejected the terms “racial minorities” and “visible minorities.” I infused the term “racialized” with implicit recognition that the conduct of the perpetrator and harms resulting from racist conduct were pivotal. I would state now as I did then: I am not disadvantaged because I am a Black woman. I am disadvantaged by racism and sexism. The people of colour referred to by King are today’s racialized people. Balking at the term “racialized,” as some have done, makes plain that King’s speech and body of work are not understood.

It is not identity politics to engage in targeted programming any more than it is ageism to have some programming directed at children and youth and some directed at our elders.

Canadians are justifiably proud of our diversity. But attention to diversity means that we must examine the impact of policies and programs to determine not only whether there is access to them, but also that they are of equal benefit to all. Human rights legislation and the Charter mandate specific attention to those facing heightened vulnerability to the compounding impact of discrimination. When combined, these strategies result in meaningful inclusivity.

It is not identity politics to engage in targeted programming any more than it is ageism to have some programming directed at children and youth and some directed at our elders. Focusing on Group A does not foreclose a distinct approach to the needs of Group B. Resources must be shared. There are distinct and known barriers that deny equal access to the benefits and entitlements of our society. Those who would deny strategic policy-making directed to racialized communities face a legitimate expectation to name their alternative strategy to eliminate systemic discrimination.

Current issues faced by Black Canadians — including deep systemic racism in the criminal justice system, challenges in the education system, poverty and profound workplace inequality — are firmly rooted in the politics of engagement that King himself advanced. King decried both the continuing “withering injustice” of slavery and its contemporary impact. He also spoke of the victimization of Black people by police. His legacy calls for leaders to stand before nonracialized communities to lance the fear forged in ignorance. They will be welcomed as they acknowledge the realities of racial profiling by standing firm in the spirit of King with the Black community in calling for its immediate eradication.

Martin Luther King Jr. did not advocate colour-blind politics. He was consistent and specific that his work was grounded in the lived reality of the injustices faced by Black people and sought solutions that reflected an understanding of racism’s transgenerational impact. He worked in coalition with others when they shared his goals, but he was not an apologist who sought to make white people comfortable in their racism. He viewed redress as an urgent matter. King called for immediate action and cautioned against “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.”

Those who assert that attention to the specific needs of the Black community, or racialized communities collectively, impoverishes or steals resources from the white community are themselves fomenting racism. King spoke of the “bank of justice” owing a debt to Black people. This is still true today and will continue to be the case as long as systemic racism persists. The proposed programs are credit against the outstanding debt where we seek not financial wealth but “the security of justice.”

Photo: Shutterstock

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.