Donald Trump’s unexpected election victory and first months in office have understandably caused Canadians to revisit some basic questions about our own democracy. It is a worthwhile exercise but it should not be an ideological or partisan undertaking. The principal questions are not about how or whether someone with President Trump’s policy or political vision could find resonance here. Instead, the questions we must confront relate to how the American media and the political class were so disconnected from the lived experiences of so many people that they failed to understand the level of collective frustration and demand for change.

Is such a disconnect possible here in Canada? Are there political cleavages that we fail to see? What can we do to protect against fissures growing among us?

Answering these questions must be near the top of our political agenda and there are no silver bullets. Changing the electoral system, for instance, may be worth debating on its merits, but surely the deep divisions we are witnessing in the US would not be avoided by turning to preferential ballots or other forms of proportional representation. There was something deeper at play that we must come to understand if we are to protect against similar polarization in Canada.

The urban/rural divide in general and the growing population concentration in a small number of major urban centres is one potential seismic fault line that requires greater thought and care on the part of Canadian politicians and policy-makers. Increasingly our economic, political and social dividing lines may be found between Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, and everywhere else. A failure to reconcile the different concerns, interests and aspirations of urban and rural Canadians could reproduce the disconnect shaping present-day American politics.

We must ensure that our politics provides proper representation for all Canadians, from Thunder Bay to Toronto and everywhere else in the country.

A growing economic, political and social divide

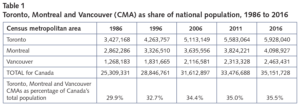

Data from the 2016 census show that Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver now represent more than 35 percent of the national population. This share has been steadily growing over the past 30 years (see table 1). Notwithstanding Canada’s vast geographic area, the country’s population is highly concentrated and increasingly so.

As a point of comparison, the US population is less concentrated in a small number of major urban centres. The population in the three largest US metropolitan areas — New York, Los Angeles and Chicago — is 52.3 million, or 16.3 percent of the national population.

Canada’s concentration of people in three major urban centres has broad-based implications. One is the disproportionate economic influence of these cities. Toronto and Vancouver were the country’s fastest-growing economies in 2016 and were at one point responsible for all net new job creation. They are also projected to experience the largest economic gains this year.

These cities are home to Canada’s richest communities, highest levels of immigration and considerable economic dynamism as seen in their many start-up firms and burgeoning industries. They are increasingly the principal locales for economic opportunity.

And this, of course, brings unique opportunities and challenges, including pressures on housing affordability and public transit and other urban issues. It is notable that despite significant labour market demand, recent evidence shows that people are leaving these three major centres much faster than they are migrating to them.

This population divide also plays out in our electoral politics. These three cities now have more than 60 federal parliamentary seats, and the number is even higher if one counts surrounding areas such as Brampton and Mississauga in Ontario, Langley and Surrey in BC or Laval in Quebec. But with a narrow definition of the cities, they still represent nearly 20 percent of all federal ridings and are thus larger than all provinces but Ontario and Quebec. These cities therefore make up arguably the most important voting bloc in the country.

It is increasingly an arithmetical and political truism that these major urban centres effectively have a veto over our politics. A political party cannot form government without substantial support in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. The 2015 federal election is a good example. The Conservative Party was shut out in these three cities (trailing the Liberal Party by 14 percentage points in and around Vancouver and 16 points in and around Toronto, for instance), and this had major implications for the overall national result.

The dynamic in the United States is not quite the same. Trump lost New York, California and Illinois and was still able to win the presidency, in large part because of the diffusion of the US population. The rest of the country matters more in political terms than it does here.

The political incentives therefore favour dedicating a significant share of attention and resources to these cities. A pre-election analysis of Justin Trudeau’s 2015 travel schedule as Liberal Party leader found that he visited Toronto (and surrounding areas) for more than one-third of his nationwide travels in the lead-up to the 2015 election. Dedicating time and resources in this way is a logical response to the political dynamic caused by the concentration of millions of voters. Economists might say it is simply a case of public choice theory in practice.

What effects can this divide have?

With this concentration of political influence in three Canadian cities, we risk seeing a gulf take full shape. As the American political commentator Michael Barone has recently written, “Capital vs. countryside — that’s the new political divide, visible in multiple surprise elections over the past eleven months. It cuts across old partisan lines and replaces traditional divisions — labor vs. management, north vs. south, Catholic vs. Protestant — among voters.”

New America’s Michael Lind has also argued the urban/ rural divide is part of a broader realignment in American politics along with other divisions, such as coastal/middle America, nationalist/cosmopolitan and white/nonwhite.

The growing urban/rural divide in Canada could lead to similar, equally divisive realignments in our politics, too. The oversized cultural and media influence of our major cities undoubtedly exacerbates this possibility.

The risk, of course, is that our media and political class become an echo chamber. Many of the people in these professions live and work in our major cities and socialize with those who have the same lived experience. It is not that they are necessarily dismissive or disdainful about how the rest of the country lives. It is that they do not even know that others live and see the world differently and prioritize different things. It is mostly a case of unthinking neglect rather than outright condescension. But the consequences are often the same.

The flip side, though, can be equally true. Those in major urban centres face issues and challenges that are not top of mind for Canadians in other parts of the country. Concerns about housing affordability or urban poverty and homelessness or maintaining a community ethic in a heterogenous environment acutely affect urban centres. Where broader consensus is needed to overcome these challenges, the urban/rural divide may prevent the necessary national conversations from happening.

These divisions are a larger-scale version of what happens within urban centres, too. Low-income, inner-city neighbourhoods in big cities, for instance, also struggle to have local media and politicians and policy-makers prioritize their concerns in a way that reflects their community’s sense of urgency. Community leaders in the Jane and Finch neighbourhood of Toronto, for example, have worked tirelessly through the Toronto Strong Neighbourhoods Strategy or the #JaneAndFinchVotes civic engagement initiative to have their local needs addressed by city officials. Finding a political voice within a city is difficult when the agenda is mostly set by the concerns of professions who are disconnected from economic and social challenges in disadvantaged parts of a city.

The same underlying challenges are thus present in the growing divide between our major cities and the rest of country. It is principally about a representative politics in which the concerns, interests and aspirations of all Canadians are part of the agenda. A politics that meets this test is critical to precluding the polarization witnessed in the US and elsewhere.

What can we do about it?

Cultivating a more inclusive and respectful politics is, of course, easier said than done. Empathy is a big part of the solution. We must force ourselves to step out of our respective bubbles and try to understand the experiences and perspectives of others. Folks from Toronto should spend more time in Thunder Bay and vice versa. We may discover we can learn more from listening to different voices.

This is particularly important for the media and political class, who play a disproportionate role in political discourse and therefore determine to a considerable extent how regular people feel about the responsiveness of our politics. The disproportionate media attention paid to the 2010 census flap would have almost certainly seemed weird to most Canadians, who at the time regularly cited jobs and the economy as their principal concerns. A bit of perspective could go a long way.

That regional newspapers have lost their correspondents in Ottawa has only exacerbated the problem. These reporters played a critical role in both placing regional or local issues on the national agenda and conveying federal decisions in a way that connects to regional or local concerns. Reversing this trend is beyond the scope of this article, but a first step can be for journalists and politicians to venture out beyond our major urban centres.

And this cannot just be about photo ops or media reports that treat nonurban Canadians like exotic animals spotted on a safari. There is a need to go and listen, and then to report and act. The American photojournalist Chris Arnade offers a useful model in this regard. His journalistic work in so-called “Trump country” over the past two years has been deeply insightful. This could be a first step in enabling a better, more responsive politics.

We could also benefit from greater diversity in our politics, such as including more working-class voices from inner-city neighbourhoods and rural ridings. We do not necessarily need the first 2,000 names from the phone book, as the American conservative writer Bill Buckley famously observed, but surely we can do a better job of bringing more representative voices into formal politics. A 2013 American study found that, of the 783 members of Congress who served between 1999 and 2008, only 13 percent had spent more than a quarter of their previous career in blue-collar work. There are no similar Canadian studies to our knowledge, but a cursory review of the federal cabinet suggests that the figure here would be no higher.

This does not mean we need quotas or top-down diktats. Imposing one form of diversity is bound to create demands for other mandates in a never-ending cycle. Instead there are opportunities for grassroots initiatives, such as CrowdPac, a US-based crowdsourcing platform for political candidates, or the Manning Centre’s political training here in Canada to help level the playing field for nontraditional candidates.

There is also a role for political parties and the media in this regard, but it may not be the one that people necessarily think. It is less about setting targets for certain types of candidates and more about enabling greater diversity of opinion and resisting the temptation to play “gotcha” politics if a candidate does not sound like a typical politician. But as long as it continues to be a scandal when a candidate goes off script or espouses an unorthodox position, the tendency will be the professionalization of our politics.

Government appointments are also an area in which nonurban or working-class voices are almost certainly underrepresented. Governments regularly create panels or commissions or advisory bodies, and those who populate them are drawn from a small cast of predictable characters. There should be a greater effort to draw on voices from outside the major urban centres and from a range of backgrounds, experiences and perspectives.

The new process for Senate appointments is one means of achieving progress in this regard. The Trudeau government’s first rounds of appointments have been geographically distributed (including some appointees with nonurban backgrounds) and self-evidently qualified. A disproportionate share, however, are drawn from professional classes such as university professors, who make up roughly one-third of appointees thus far. Greater focus ought to be placed on drawing in people with more diverse personal and professional backgrounds to ensure that the Senate is more representative.

A final step would be to draw more on federalism and localism to address issues and solve problems. One of the major causes of political tensions and agitations is the perception that a government is favouring one region or city over others. Nationalizing every issue exacerbates these feelings.

The solution is to devolve more decision-making so that communities have more autonomy and power to choose their own paths and solutions. The role of the national and provincial governments should be limited primarily to matters of national or province-wide interest. Translating this subsidiarity principle into action could have significant implications for fiscal federalism, the design of government programming and delivery of services, and the role of civil society.

Not only could such a vision help to reduce political tensions, it could also create the conditions for experimentation, competition and the translation of best practices among communities. It would effectively establish a community-based laboratory for politics, policy and representative democracy.

Donald Trump’s unexpected presidency should be a sign that Canadians must think about our own democracy and how well it serves all Canadians. The growing population concentration in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver could have political implications that we ought to be cognizant of if we are to avoid the ossification of barriers among us. The goal should be a politics that is more inclusive, responsive and respectful. We have the tools to do it. It will just require the foresight and the will.

This article is part of the Public Policy toward 2067 special feature.

Photo: The former Maitland District Elementary School, in Maitland, N.S., was shuttered in 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Andrew Vaughan

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.