Did the CBC Fifth Estate really demonize pregnant migrant women in its investigative report into the number of non-resident births in Canada? That is the argument made by Megan Gaucher and Lindsay Larios, writing recently in Policy Options. A letter of complaint was also submitted about the report to the CBC Ombudsperson by 30 organizations, including groups representing migrant workers. Is discussion of birth tourism essentially a form of xenophobia given its focus on visible-minority foreigners? Or are the underlying concerns of the critics less about birth tourism and more about gaps in healthcare coverage for temporary residents?

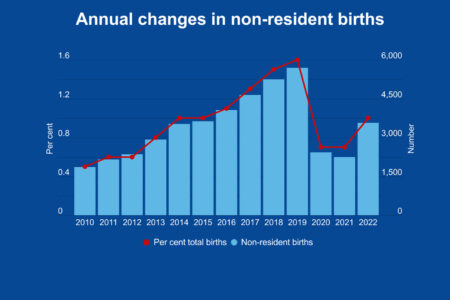

Critics of the Fifth Estate report take issue with an analysis I did in 2018 using hospital financial data from the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) and the financial code “non-resident self-pay.” Using my data, the Fifth Estate reported that there are 5,000 non-resident births every year in Canada. I estimated that roughly half of all non-resident births were due to birth tourists. (I provided my CIHI-based analysis to the Fifth Estate and its journalists updated the Quebec hospital numbers.)

The essence of the current criticisms and earlier critiques is that the “non-resident self-pay code” in the hospital data includes all temporary residents (students and foreign workers, for example), not just those on visitor visas. Any change to birthright citizenship would affect not only those on visitor visas but also other categories of temporary residents.

Let’s be clear – the data should be more precise.

My 2018 analysis prompted the November 2018 announcement of joint work by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, CIHI, and Statistics Canada to integrate healthcare and immigration data. This should allow for separation of the numbers of those here on visitor visas from other categories of non-residents (international students, temporary foreign workers and those using the International Mobility Program). Data on visitor visas will not distinguish between those here for birth tourism versus other non-resident births, but it will provide the most accurate indication possible, along with information on countries of origin, which has been largely anecdotal.

Having a better sense of the demographics of women coming for birth tourism could help broaden the discussion. Given the recently announced change by the US government to make birth tourism grounds for visa refusal, this more precise data will also facilitate analysis of whether the US restriction leads to more birth tourists choosing to come to Canada.

But more-precise data is likely to simply reaffirm that birth tourism is not significant in relation to total births nationally, though it is pronounced in specific communities – such as Richmond, BC, where more than one in five births is believed to be part of birth tourism. This suggests that regulatory approaches would be more appropriate than a change to birthright citizenship. Regulatory approaches could include higher deposits and medical insurance requirements for non-Medicare covered deliveries, scheduling preference given to Canadian residents, and municipal zoning regulations regarding birth tourism residences. A change to birthright citizenship would be costly and more complicated for all Canadians.

There is an argument that says raising birth tourism concerns by singling out women who are visible minorities is xenophobic or contributes to anti-immigrant discourse. This is debatable. Certainly, there are some xenophobic elements to this discussion. But questioning the extent of birth tourism, the nature of the clientele, the supporting “cottage industry” (consultants and pre- and post-birth residences), as the Fifth Estate episode does, does not demonize all visible-minority pregnant women. Birth tourism services cater to wealthy women who can afford the associated travel and accommodation costs and medical fees, typically packaged by consultants for a price tag of about $60,000.

Similarly, raising the question of the possible need for legislative or regulatory changes to reduce the practice is not necessarily xenophobic or anti-immigrant. After all, Chinese-Canadians make up the majority of residents in Richmond, the epicentre of birth tourism in Canada, which means their access to perinatal care is most affected by the impact of birth tourism.

Perhaps it would be better to frame birth tourism as more of a class or equity issue. It is wealthy foreign women who essentially have an “express lane” to citizenship for their children using costly consulting and other services, whereas less affluent immigrants have to comply with citizenship requirements. Birth tourists are not vulnerable, marginalized women.

Critics say the discussion about birth tourism overshadows broader and legitimate concerns about gaps in healthcare coverage for all temporary residents, since coverage depends on the category, province of residence, duration of work permit and other factors. Those who are here using the lower-skilled Temporary Foreign Worker Program are more vulnerable than those who have come through the International Mobility Program or are international students.

These differences and gaps of healthcare coverage for temporary residents apply to all healthcare services, for men as well as women, with perinatal care being a minor portion of non-resident healthcare services. Expansion of health care to address these gaps as advocated by the analyses by Gaucher, Larios and the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, would, of course, raise much broader issues than those related to birth tourism, particularly issues of affordability for governments given the financial implications of extending Medicare to all or most temporary residents.

Future research will benefit from isolating the number of children born to non-resident visitor visa holders from other temporary residents and by isolating data by country of origin. Rather than labelling concerns about birth tourism almost automatically as xenophobic, and all temporary-resident women as vulnerable, more nuance and differentiation is required to advance understanding and discussion of the extent of birth tourism, whether or not government action is needed to reduce the practice and, if so, what are the strengths and weaknesses of the various options available.

Photo: Shutterstock, By sukanya sitthikongsak

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.