As Canada’s job losses mounted dramatically in the 2009 post-budget months, the focus of parliamentary attention has shifted from the adequacy of the Harper government’s stimulus package to concern that the timeliness, level and duration of EI benefits were not meeting the needs of our rapidly growing numbers of unemployed. Such concerns, of course, predated the fallout from the current deep recession. For example, critics have noted that Canada (along with the US) has the lowest benefit-replacement rate among major OECD countries. Indeed, the generosity of EI benefits has been in more or less secular decline ever since the expansive (and expensive!) 1971 revisions that both broadened coverage and enhanced benefits. Critics are also rightly concerned about the inordinate interregional variability in the ratio of EI beneficiaries to the unemployed, which runs from roughly 90 percent in Newfoundland and Labrador to the 20-40 percent range for the five westernmost provinces. This widely differential coverage is attributable to the variable entrance or qualification requirement (VER), which ranges from 420 hours (12 weeks at 35 hours) in regions of high unemployment, to 700 hours (20 weeks) in regions where unemployment is relatively low.

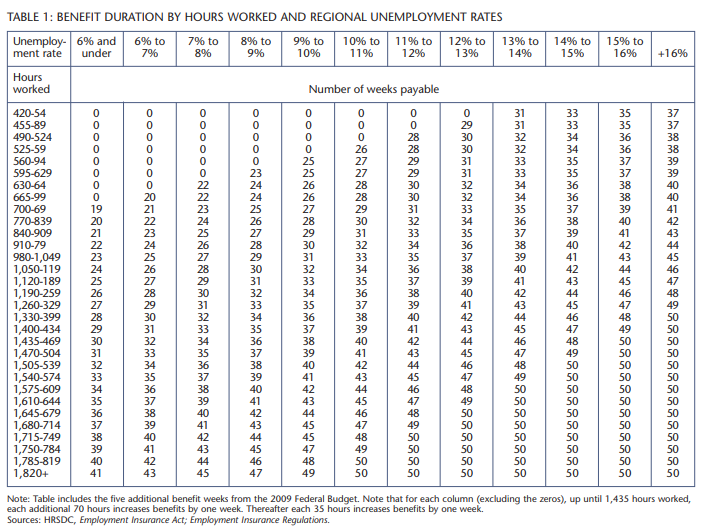

The problem of differential access or coverage is exacerbated by differences in the duration of benefits, which increase by two weeks for every percentage point that the regional unemployment rate exceeds 6 percent. This complex relationship between the VER, weeks of benefits, and the unemployment rate is shown in table 1, which incorporates the five-week extension of benefits contained in the 2009 federal budget. The Caledon Institute recently noted that the operation of these complex relationships contributed to the finding that in Toronto and Ottawa the percentage of the unemployed who qualified for EI, was less than half that in some other cities (e.g., St. John’s and Quebec City), while the absolute percentages were very low (20 percent for the Ontario cities, and 50 percent for the others).

Most telling of all, however, were the recent unemployment data. While a record 778,000 Canadians received EI benefits in May (a number that is expected to increase in the near term), over 800,000 unemployed Canadians and their families were without EI benefits. Not surprisingly, as the economic crisis deepened, issues relating to EI came to dominate the Commons agenda, with many parliamentarians arguing that the five additional weeks of benefits and other changes included in the budget were an insufficient response to the crisis. Included among the many issues raised were whether there should be a uniform national qualification period (which, for the immediate term, would presumably mean choosing something closer to the low end of the 420-700 hours VER); whether the two-week waiting period should be eliminated (which Harper thus far refuses to do); whether the 2.6 million self-employed Canadians should be integrated into EI; and whether to legislate extended benefits beyond the five weeks that Harper has already enacted.

While a record 778,000 Canadians received EI benefits in May (a number that is expected to increase in the near term), over 800,000 unemployed Canadians and their families were without EI benefits. Not surprisingly, as the economic crisis deepened, issues relating to EI came to dominate the Commons agenda, with many parliamentarians arguing that the five additional weeks of benefits and other changes included in the budget were an insufficient response to the crisis.

A Commons confidence vote on these issues, scheduled for late June, was postponed until late September by virtue of a Harper-Ignatieff agreement to create a Conservative-Liberal working group to report on them when Parliament resumes after the summer recess. Given the context of the current economic crisis and the pending confidence vote, EI reform will take centre-stage when Parliament resumes later this month. Lending urgency to the debate will be the fact that, unless Ottawa is about to extend existing EI benefits repeatedly, or unless the economy gathers unexpected steam, many tens of thousands of Canadians will already have exhausted their EI benefits (or will be in the process of doing so) and will be forced to resort to provincial welfare. What happens then? Does Ottawa increase the Canada Social Transfer to the provinces, or does it leave the provinces to fend for themselves in dealing with what will surely be mushrooming welfare rolls?

While these short-term issues obviously merit attention, the ensuing analysis will also emphasize the necessity of relating any short-term responses to the longer-term evolution of policy, including long-standing concerns with the equity, efficiency and moral hazard aspects of UI/EI. In this context, two other concerns motivate our assessment of EI. The first is that the structure and breadth of EI make it most difficult to create an appropriate, integrated model for social Canada in our increasingly knowledge-based economy and society. The second is that while UI/EI has admittedly been at the forefront of enhancing our social envelope (e.g., maternity, parental, compassionate, sickness and training benefits), we nonetheless seem to be following in the footsteps of the Americans by requiring a good job (i.e., requiring EI eligibility) to gain access to these benefits. For example, only one in three new mothers accessed maternity benefits, in part because they were not EI-eligible and in part because they were EI-eligible but the benefit levels were inadequate. If our social policy goal is to provide equitable treatment for all Canadians, these programs should, to the extent possible, be citizen-based (like medicare) and not employment-based along US lines.

To provide an historical context for our discussion, the analysis begins with a brief and selective overview of the evolution of UI/EI. This will be followed by a similarly selective review of the recommendations of two Royal Commissions that were mandated to investigate the operation and consequences of the program. The stage will then be set for addressing alternative ways of rethinking EI in Canadian industrial, social and regional environments. While it is probably too much to expect that the September EI proposals would reflect these more fundamental perspectives, one might hope that any changes that emerge will not serve to create additional entitlements that may impede the evolution of a state-of-the-art social envelope for all Canadians.

Canada’s first unemployment insurance program was enacted in 1935, as part of R.B. Bennett’s “new deal.” However, the legislation was quickly struck down in 1937 by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on grounds that both “employment” and “insurance” fell under provincial powers (namely s.92 (13) “Property and Civil Rights in the Province”). This led to the 1940 constitutional amendment, which added “unemployment insurance” (as the substance of the new s.91(2A) to the list of exclusive federal powers, followed closely by Mackenzie King’s Unemployment Insurance Act of 1940, an Act solidly predicated on sound insurance principles. Prior to describing some of its features, we note this constitutional amendment represents a key turning point in Canada’s social and regional history, since it provided Ottawa with an instrument that allowed it not only to circumvent “property and civil rights” but, as well, to fragment the internal social and economic union, as long as the issues in question could somehow be linked to unemployment insurance. It has been used, for example, in the following ways:

- To help shape industrial Canada by providing seasonal benefits to workers in seasonal industries and by extending benefits to self-employed fishermen (but not, it may be noted, to farmers);

- To give fiscal policy a regional dimension (VER based on regional unemployment rates and different benefit packages), although the resulting differential treatment of otherwise similarly situated Canadians has obviously been at the expense of horizontal equity;

- To achieve fiscal balance in the post-1996 era by diverting nearly $60 billion in excess EI premiums into Ottawa’s consolidated revenue fund (see figure 2);

- To expand Canada’s social envelope by providing maternity, parental, sickness, compassionate and training benefits; and

- Potentially to become the chosen instrument for addressing income support for Canada’s unemployed workers, a topic on which more is said below.

The inaugural 1940 UI program covered nongovernment regular workers with incomes under $2,000 — a group that included just over 40 percent of the labour force but excluded some categories (e.g., seasonal workers) most likely to experience unemployment. The entrance requirement for benefits was 180 days of employment (or 30 weeks, assuming a 6-day week) over the previous two years. Premiums were 1.8 percent of insured earnings (up to the average industrial wage) for both employees and employers, with the government contributing an amount equal to 20 percent of total premiums and covering the administrative costs. Benefits were set at 34 times the 1.8 percent premiums, for a replacement rate of roughly 60 percent. Benefits were limited to one day for each five days of contributions in the preceding five years, or to one year for someone with five years of continuous employment. All in all, it was a model driven largely by insurance principles.

While it is probably too much to expect that the September EI proposals would reflect these more fundamental perspectives, one might hope that any changes that emerge will not serve to create additional entitlements that may impede the evolution of a state-of-the-art social envelope for all Canadians.

During the 1940s coverage was increased, and by the end of the decade approximately 50 percent of all workers were covered. Benefits also were expanded to provide supplemental seasonal benefits as well as assistance for homecoming soldiers. The most dramatic development during the 1950s and 1960s, and the most significant departure from insurance principles, was the extension of UI to cover self-employed fishers. This created very significant moral-hazard issues and, arguably, led to overfishing and the subsequent demise of aspects of the fishing industry. Despite these lessons, extending coverage to self-employed Canadians nonetheless appears to be high on the policy agenda for September. Other developments included the introduction of modest sickness benefits and a reduction in the eligibility requirement from the earlier 30 weeks to 24 weeks, and the coverage level was increased to about 2/3 of the labour force.

The real watershed, however, in the evolution of UI/EI was the passage of the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1971. Coverage became nearly universal, largely as a result of the inclusion of employees for whom the likelihood of unemployment was very low — notably public sector employees at all levels of government. Moreover, coverage in terms of the range of benefits was also extended to “special benefits” (sickness, maternity, retirement). Entry requirements were reduced dramatically from 24 weeks to 8 weeks. In 1977 this 8-week requirement gave way to VERs of 10-14 weeks, then 12-20 weeks in 1994, and finally to an hours-based approach in 1997. For the roughly 60 EI regions, the current VERs run from 420 hours for those regions with 13 percent unemployment or higher, to 700 hours in regions with 6 percent unemployment or lower. The still-operative 1971 contribution structure set employer premiums at 1.4 times those for employees, and premiums were levied on insurable earnings up to the maximum level (again, the average industrial wage). The premium rates were set to ensure that the system would be self financing at 4 percent unemployment, excluding special benefits. In other words, there were substantial stabilization and social-policy components built into the 1971 version of UI: Ottawa bore the costs of benefits arising from unemployment rates above 4 percent, as well as those for fishing and for sickness, maternity, and retirement benefits.

Benefits were set at 75 percent of insured earnings for claimants with dependents and 66 percent for those without. The frequently changing regulations relating to the duration of benefits were typically based on weeks worked, the national unemployment rate and the various regional unemployment rates. For example, the 1994 structure for regular benefits was as follows (drawing from Zhengxi Lin’s 1998 Perspectives article): a work component providing up to 20 weeks of benefits (1 week of benefits for every 2 weeks of work for the first 40 insured weeks); up to 12 additional weeks of benefits (1 for each additional week of work beyond 40); and a regional component of up to 26 weeks of benefits (2 for every percentage point by which the regional unemployment rate exceeded 4 percent), all subject to a maximum entitlement of 50 weeks. In passing, it may be noted that while it may have had some hortatory value as a target or ideal, the 4 percent threshold used to determine weeks of regional benefits was a level never in fact achieved nationally, let alone in the areas subject to regional benefits. It would appear, therefore, that its primary purpose was to effect an ongoing interregional transfer of benefits. Moreover, allowing claimants who worked in a low-unemployment region to file for benefits in a high-unemployment region contributed to the size of this transfer.

Compared to the previous iterations of UI, the 1971 Act shifted the program quite dramatically away from insurance principles. Perhaps the most evident manifestation of this was the famous — or infamous! — 8/42 syndrome: 8 weeks work in the highest unemployment region would, after the 2-week waiting period, allow one to claim UI benefits for the following 42 weeks of the year. This practice of allowing short-term labour force attachment to trigger long-term UI/EI benefits still plays a key role in the system. Thus working 420 hours will trigger 31 weeks of benefits in a region with 13 percent unemployment and 37 weeks if the rate is above 16 percent. In contrast, in a region where the unemployment rate is below 6 percent, one needs 700 hours to even qualify and 1,680 hours (four times the 420 hours entry level) to be eligible for 37 weeks (table 1). Perhaps an even more extreme example of short-term labour-force attachment triggering long-term benefits is provided by the requirements for self-employed fishers. In this case, as little as $2,500 of income from self-employed fishing may trigger 26 weeks of benefits. The moral-hazard consequences of such arrangements have already been alluded to and should certainly give pause to those seeking to bring all self-employed persons under the EI umbrella.

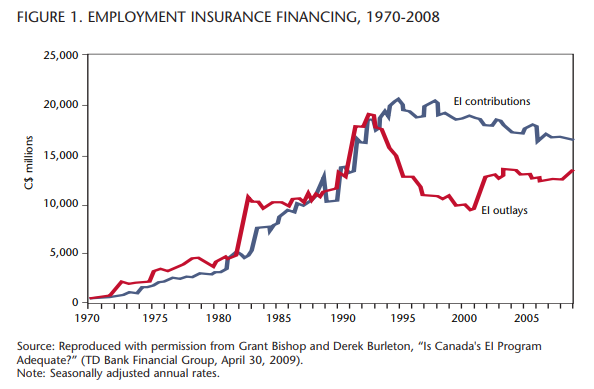

With lower entry requirements, extended coverage and higher replacement ratios, it is hardly surprising that post-1971 UI costs mushroomed. Indeed, post-implementation outlays vastly exceeded forecast costs, and the resulting overrun, which was almost certainly attributable to an underestimation of the moral hazard effects of the enrichment, was huge and embarrassing. Further rapid increases occurred during the recessions of the early 1980s and 1990s, when, as shown in figure 1, outlays doubled and then redoubled. Given the actuarial requirements of the program, these burgeoning outlays triggered increases in premiums, which from 1980 to 1994 more than doubled, those for employees rising from 1.35 percent to 3.07 percent. As the economy recovered from recession, the fund moved into surplus, and premiums once more fell back to more sustainable levels under 2 percent.

Equally unsurprising, this escalation of outlays led to a series of measures to reduce the total cost of EI, most particularly the cost to the federal government. In 1996 the Act was amended to raise entrance requirements for new entrants and re-entrants to 900 hours, and the qualifying period for special benefits was set at 700 hours. Repeat claimants were faced with a benefit clawback of up to 100 percent if earnings on claim exceeded maximum insurable earnings, and the replacement rate was reduced. Despite these moves to control outlays, there were still some important extensions of coverage (parental benefits, for example, were phased into EI, with the December 2000 changes extending the total period of maternity and parental benefits from 25 weeks to 50 weeks). Also, the 1996 Act effectively distinguished between unemployment benefits and employment benefits (i.e., between those benefits linked directly to unemployment, and those attributable to being employed), formally altered the name from UI to EI, and converted the 12-20 weeks VER into 420-700 hours (at 35 hours per week). Despite these developments, the general thrust in terms of regular benefits was toward increased restraint.

Since any unshifted premium burden is likely to encourage or force employers to adopt more capital-intensive and labourdisplacing production processes, the presumption is that the burden of employee and employer premiums will largely be borne by employees in the form of lower wages than would otherwise prevail. The rationale for requiring employer premiums to be 1.4 times those of the employees would therefore appear to be largely political salability.

Most importantly for Paul Martin’s later role as deficit slayer, the federal government’s role in financing UI/EI came to an end in 1990. In consequence, the entire cost of the system is now underwritten by employers and employees. With contribution rates set to eliminate the cumulative deficit from the 1990s recession, and with the sharp fall in benefits as a result of the subsequent boom and the restraint measures identified above, the EI surplus rose to the $6 billion range in 1996 (see figure 1). Indeed, as figure 2 shows, over the period from the end of the 1990s recession to 2008, the accumulated EI surplus, which went directly into Ottawa’s coffers, reached $60 billion. Interestingly, for the forecast period shown in the figure, the TD Bank “status quo estimates” (including 2009 budget changes) indicate an initial fall in the accumulated surplus but a recovery to the 2008 level over a decade.

The fall 2009 parliamentary sitting will presumably be the next iteration in EI reform. The clear difference from the recent past is that all the pressures on EI point to an expansion of the program (the chief contenders for this expansion were highlighted in the introductory paragraphs of this article). Unfortunately, none of these options goes beyond the confines of the parameters of the existing EI program to situate the program in a larger and more appropriate context. Accordingly, we now consider the recommendations of the two Royal Commissions that proposed more radical reform of the EI system, recommendations that condition our own proposals for reform.

The first of these is from an unexpected source — Newfoundland and Labrador (henceforth NL) — the report of the 1986 Newfoundland Royal Commission on Employment and Unemployment. With by far the highest ratio of benefits received per dollar of premiums paid, NL was arguably the province that benefited most from the operation of what was then still UI. The Commission was nonetheless rather scathing in its condemnation of the impact the program was having on the provincial economy. A selection from the Commission’s litany of the ills wrought upon the province by UI appears in the box. In its colourfully straightforward prose, the Commission notes that “while it would be socially unacceptable, economically disastrous and politically suicidal simply to cut back drastically on UI payments to Newfoundland without providing alternative income support and income supplementation… it is eminently possible to undertake a redesign of the entire income security system.” In more detail, what the Commission had in mind was a three-fold system: income support in the form of say a guaranteed basic income for all; income supplementation in the form of, say, an earnedincome tax benefit (or what we now call a working-income tax benefit); and income maintenance in the form of UI/EI and worker’s compensation. While the devil is always in the details when it comes to overarching approaches that bridge program areas and levels of government, this conception of a reworked social Canada still has merit, especially given its provenance. The Commission went so far as to suggest that if Ottawa were to provide NL with the current money flowing into the province from existing programs, the province would work with the federal government to implement the Commission’s proposals, thereby providing a model for other provinces to emulate.

The second reference document is the report of the 1985 Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada, generally referred to as the Macdonald Commission. In terms of the welfare-work subsystem, the Macdonald Commission also opts for a three-pronged approach: reworking UI/EI to more strongly reflect insurance principles; creating a transitional adjustment assistance plan (TAAP); and embarking on a universal income security program (UISP). Among the recommendations for EI are 1) reducing the benefit rate to 50 percent of earnings; 2) raising entrance requirements to 15-20 weeks; 3) eliminating any regional differentiation within UI/EI; and 4) tightening the link between contribution weeks and benefit weeks by requiring two or three weeks of work to qualify for one week of benefits. The Commission was able to opt for this stripped-down-to-basics insurance version of UI/EI only because of the TAAP and the UISP.

The TAAP would have been an omnibus program related to, but independent of, the UI/EI program, one designed to assist the labour force to adjust to opportunities and challenges. Among other things, it would have provided on-the-job training, earned income tax credits, and mobility grants. Funding would have come from the elimination of regional benefits (which, at the time, were still financed by Ottawa) and by the tax room created by lower UI/EI premiums. UISP was the Commission’s proposal for a guaranteed annual income or a negative income tax (GAI/NIT). It would be funded inter alia by the diversion of resources from what were then CAP transfers, family allowances and the personal exemptions and credits in the income tax system. Because so much has altered on the tax-transfer front since the Commission’s report, the message to take from the UISP proposal is its role, not the precise funding arrangements in the time frame of the mid-1980s.

Armed, as it were, with the history of UI/EI and two versions of an integrated welfare-work subsystem, we now return to the September EI challenge for our parliamentarians. At first blush, these challenges are clearly short-term; namely, how to rework aspects of EI so as to accommodate the needs of Canadians who either are or soon will be unemployed as a result of the global financial and economic crisis. However, this framing of the issue is inadequate in at least two respects. First, and most important in the short term, the challenges of the unemployed transcend EI, especially for those who are not EI-eligible or have exhausted their EI benefits. Second, the manner in which we deal with these short-term challenges may not be consistent with the longerterm evolution toward an integrated welfare-work system. In turn, these considerations suggest that the preferred way to approach EI reform is to begin by elaborating on the characteristics of an integrated welfare-work subsystem as part of our overall social envelope.

Our view is that most of what falls under these benefits is better viewed as part of the larger Canadian social envelope. These benefits should, therefore, be funded from general revenues; to the extent possible, they should be available to all Canadians rather than only to those who are EI-eligible; and most certainly they should not be run through the current regime, where employers pay, at least in the first instance, 58 percent of EI costs.

To this end, we draw from the earlier UI/EI history, from the visions embodied in the two Royal Commissions and, of course, from our own perspectives/biases. Our starting point is to note again that the 1996 EI Act distinguished between unemployment and employment benefits. Focusing on the former and, specifically, on regular unemployment benefits, our first point is that these should be funded by premiums set in general accordance with insurance principles. In our view this means not only a uniform entrance requirement but, as well, a uniform way of calculating the duration of benefits. In terms of the latter, the Macdonald Commission’s proposal provides one example. A more generous approach would be 1 week of benefits for each week of contributions for the first 15 weeks of work, a further 1 week of benefits for each two 2 weeks of work for the next 30 work weeks; and beyond that, 1 additional week of benefits for each 3 additional weeks of work, to an overall maximum that could be the current 50 benefit weeks or could follow international practice and provide longer maximum benefits. This would ensure equality of treatment for all unemployed Canadians and it would guard against the risk of short-term labour-force attachment triggering long-term benefits. In terms of buttressing the proposal for a uniform entry requirement, in addition to the obvious equity case, several commentators have noted that in this recession it is not evident that it is any easiertofindajobinalow-thanina high-unemployment-rate region, which was presumably a major part of the original rationale for the easierentry and longer-duration provisions in high-unemployment regions.

Second, with these insurance principles in place, together with the principle that benefit weeks can only be triggered by weeks worked, one would presumably want the uniform qualifying period to be set quite low, e.g., at the low end of the current 420-700 hour range, or even lower. As an interesting aside, there would no longer be an incentive, on becoming unemployed, to move back to a high-unemployment region to collect benefits.

Third, with the appeal of the 12week work rotation thus sharply reduced by a return to insurance principles, it is not obvious that one should have special provisions for “repeaters.” Nor would it seem necessary to have a higher eligibility requirement for new entrants to the labour force or for people returning to it after a considerable absence. Fourth, whether the model proposed here is adopted or not, there seems to be little reason for employers to be saddled with higher premium rates than are employees. Since any unshifted premium burden is likely to encourage or force employers to adopt more capital-intensive and labour-displacing production processes, the presumption is that the burden of employee and employer premiums will largely be borne by employees in the form of lower wages than would otherwise prevail. The rationale for requiring employer premiums to be 1.4 times those of the employees would therefore appear to be largely political salability.

Fifth, on moral hazard grounds we would not include the self-employed in the EI program relating to regular unemployment benefits. Finally, because EI for regular benefits will be driven more by insurance principles, premium rates will fall dramatically.

This version of an EI program for regular benefits could only be viable if it were accompanied by a new income support system. Our approach would be to follow the two Royal Commissions (and Senator Hugh Segal) in recommending a GAI/NIT for Canadians. With the child tax benefits and the old age security/guaranteed income supplement (OAS/GIS) combination already income-tested and subject to tax-back, we effectively have NITs for children and seniors. All that remains is to extend this to adults by making the basic personal and spousal amounts (and perhaps others) under the income tax refundable and payable monthly to adults, with the associated tax-back occurring in the context of filing one’s tax return. Since the provinces’ welfare costs will decline in the presence of this NIT, an obvious further source of funds for the income-support system could be the resulting savings from a reduced Canada Social Transfer.

In passing, we note that it would be important to avoid aggregate taxback rates so high as to have profound disincentive effects. This is always a potential problem with NITs and analogous programs where, if the rate is too low, benefits will not be well targeted and will flow to recipients whose income is higher than the program is designed to aid. On the other hand, if the rate is too high, unacceptable disincentive effects are encountered. In the present case, a possible candidate for consideration would be to limit the aggregate tax-back rate for all relevant programs.

In 1996 the Act was amended to raise entrance requirements for new entrants and re-entrants to 900 hours, and the qualifying period for special benefits was set at 700 hours. Repeat claimants were faced with a benefit clawback of up to 100 percent if earnings on claim exceeded maximum insurable earnings, and the replacement rate was reduced.

By way of providing a further rationale for this proposal, income redistribution is arguably most appropriately a central government function. This is especially so in a country where the regional fortunes are as variable as they are in Canada. Phrased differently, the burden of citizen adjustment in a turbulent economic environment ought to be shared by all Canadians.

Obviously the provinces will maintain their social services role within the welfare envelope and may well want to top up the GAI, perhaps even by combining the adult tax credits in their provincial income tax systems with the federal GAI. The Canada Revenue Agency could administer the program for both levels of government.

We now turn to what the current EI program calls employment benefits (maternity, parental, sickness, compassionate and training). Our view is that most of what falls under these benefits is better viewed as part of the larger Canadian social envelope. These benefits should, therefore, be funded from general revenues; to the extent possible, they should be available to all Canadians rather than only to those who are EI-eligible; and most certainly they should not be run through the current regime, where employers pay, at least in the first instance, 58 percent of EI costs. The 1971 version of UI had it right when it limited the role of income from premiums to financing regular benefits, with employment benefits and regional benefits, etc., to be funded out of Ottawa’s general revenues. One might still use the EI program as the vehicle through which to administer the employment benefits, but the funding should come from elsewhere.

Comprehensive reform of the sort envisaged here will not occur imminently. In the current time frame, Canada is probably going to follow international practice and continue to use premiums to finance employment benefits via the operations of EI. The challenge then becomes one of seeking ways of making these benefits accessible to more Canadians. There are 800,000 unemployed Canadians and their families who are not EI-eligible; there are a further 2.6 million Canadians who are ineligible because they are self-employed; and there are still others who are ineligible because they are not in the labour force (e.g., students). The equity issue (perhaps also an efficiency issue to the extent that equality of opportunity comes into play) is clear: coverage has to be extended beyond the EI-eligible group. Significantly, Quebec has realized this and has acted boldly. With Ottawa’s imprimatur, Quebec has recently embarked on its own program for maternity, parental, paternity and adoption leave under the aegis of the QPIP (Quebec Parental Insurance Program), which has the following parameters: it includes all self-employed workers; it increases the maximum insurable earnings from EI’s $40,000 to QPIP’s $57,000; it waives the two-week waiting period; and it replaces the entrance requirement with a provision that the claimant’s ensurable earnings must be more than $2,000. This is a generous and therefore expensive program: our best evidence is that the premium costs for QPIP benefits will be 28 percent higher than the relevant premium costs for employment benefits within EI. Will other provinces want to follow Quebec? Or will they wish the federal government would do so? Indeed, Prime Minister Harper has already proposed a voluntary extension of maternal and paternity benefits for the self-employed, one that would require six-months contributions prior to making a claim. Such an approach would be so rife with moral hazard and so devoid of any insurance principle that it would surely lead to a demand to remove these benefits from EI and make them citizen-based.

As little as $2,500 of income from self-employed fishing may trigger 26 weeks of benefits. The moral-hazard consequences of such arrangements have already been alluded to and should certainly give pause to those seeking to bring all self-employed persons under the EI umbrella.

There is another access issue pertaining to maternity and parental benefits, namely, some people are eligible for these benefits but forgo the opportunity because the benefit levels are too low. This needs to be addressed. Our proposal here would be along the following lines. Why not calculate what the total value of the maternal (or parental) benefits would be and then allocate this total value over a smaller number of weeks, thereby raising the weekly benefit to a liveable level. To be sure, there would have to be some maximum benefit level under this re-calibration, but this maximum should be set with the goal of trying to increase the likelihood that more of these eligible people will access the benefits. As the program stands now, one presumes that those who do access benefits tend have a secure job in a large organization that can more easily accommodate frequent leaves; e.g., larger corporations and the public sector at all levels. Moreover, since a substantial number of the people who are do not take advantage of full maternity benefits are likely to be single mothers, this is all the more reason for considering this proposal, or some reasonable equivalent.

Turning finally to the dilemma facing parliamentarians with respect to regular EI benefits, a convenient starting point is to use the architecture underpinning table 1 to assign values to the zeros in the table. In the area of the table that contains the zeros, an additional 70 hours (two weeks) of work will generate one additional week of benefits. Similarly, for a given number of hours worked, a 1 percent increase in the unemployment rate will generate an additional two weeks of benefits. Using these relationships, benefit weeks may be derived for each zero cell. The zeros in the first row (420-54 hours) of the table, for example, would now become 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29 and then the 31 weeks that is in the original table. Similarly, the values in the first column would be 15, 15, 16, 16, 17, 17, 18, 18 and then the 19 weeks of the table.

This leads to several comments. The first is that our insurance principles approach to a common benefit period for everyone with the same entry qualification (i.e., hours) yields results quite similar to those obtained in column 1 by replacing the zeros with calculated values. Since both approaches eliminate the influence of the regional unemployment rates from the benefit calculation, this is not surprising. It is unlikely, however, that the latter (i.e., replacing all the zeros by calculated values) will be on the impending policy agenda. Second, if one wants to increase access for those who currently do not qualify, why not use the “calculated” weeks in the first column for this purpose. For example, 420 hours does not qualify you for EI now unless you are in a region where unemployment is very high. One could assign the 15 weeks in the new column 1, as the new benefit level. Indeed, one could even lower the entry requirement to 350 hours (10 weeks), which, from the new column 1 if extended upward, would generate 14 weeks of benefits. This second comment would likely lead to a third from some quarters: since the above approach would yield 15 weeks for 420 hours worked up to the point where the regional unemployment rate is 13 percent (at which point the benefits jump to 31 weeks), why not use the structure of the table and derive benefit-week values for all the “zero cells” in the table.

By way of providing a further rationale for this proposal, income redistribution is arguably most appropriately a central government function. This is especially so in a country where the regional fortunes are as variable as they are in Canada. Phrased differently, the burden of citizen adjustment in a turbulent economic environment ought to be shared by all Canadians.

One could of course, do this. However, one difficulty with this proposal is that a person who is at present ineligible for benefits would, given the way the table values are calculated, become entitled to more weeks of benefits than someone already eligible and with more hours worked but in a region with a lower unemployment rate. Such anomalies are inevitable in a system where additional weeks of work earn less reward than an additional point on the regional unemployment rate. This would be avoided under our earlier proposal to apply the recalculated values in column 1 for current non-qualifiers, regardless of regional unemployment rates. This could be implemented in the short term and would have the additional benefit of being a step toward the concept of a uniform benefit period based on insurable hours only, as well as a solution to the ongoing concerns with respect to the variable entrance requirements.

We return, finally, to an earlier issue, namely, that the pressures on parliamentarians as they return from their summer recess are likely to shift from EI, per se, to the 800,000 unemployed who are without EI benefits and the tens of thousands who either have exhausted or will shortly exhaust their benefits. Can the provinces afford the requisite welfare payments? Our guess is that Ottawa will find it very difficult to avoid the conclusion that it needs to be more involved in overall income redistribution. After all, if Parliament can arbitrarily extend EI benefits by five weeks, what grounds does it fall back on to refuse to provide monies to the provinces so that their finances are adequate to ensure recently unemployed Canadians have access to welfare? A step in the direction of using the Canada Social Transfer to share in any additional welfare costs would be a welcome move toward Ottawa recognizing its role in Canada-wide income redistribution, and perhaps as a precursor to a GAI/NIT.

Two concluding comments are in order. The first is that because EI has a dedicated revenue base, because it allows Ottawa to invade provincial jurisdiction, and because it is incentive-ridden with regional and industrial subsidies, its tentacles are everywhere and are, in our view, now preventing the development of an efficient, cost-effective and state-of-the-art social envelope in this knowledge-based era. Phrased differently, EI is now as much about social policy as it is about unemployment insurance. As such it has become one of the defining features of who we are and who we want to be as a nation. This being the case, our view is that we need to rethink and rework the approach to the welfare-work subsystem of social Canada, hopefully along the lines suggested above. This leads to our final comment. Parliamentarians will be under tremendous pressure as they wrestle with EI. This is so not only because of the urgency of the unemployment crisis and the dictates of electoral politics, but as well because of the utter complexity of EI itself.

Our hope is that in spite of these pressures they will act (indeed enact) in a way that moves EI toward an equitable and efficient social contract for all Canadians.

Photo: Gordon Wheaton / Shutterstock