By an overwhelming margin, Canadians consider fresh water to be the most important natural resource to Canada’s future. By a margin of 3-1, they chose water over oil and gas as the key natural resource for Canada’s future.

In a Nanos Research poll sponsored by the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation for Policy Options, 61.6 percent of Canadians chose fresh water as the most important natural resource for the country’s future, while 21.7 percent chose oil and gas, 11.2 percent chose forestry and 3.8 percent chose the fisheries.

The poll of 1,001 Canadians was conducted by telephone between May 26 and June 1, and has a margin of error of 3.1 percent, 19 times out of 20.

In the past, Canadians have been seen by others as hewers of wood and drawers of water. But from the point of view of self-identification, water is at the very top of the list. Prime Minister Stephen Harper has positioned Canada as “an energy superpower,” but looking at these numbers, we can think of Canada as a water super-power.

Canadians clearly see water as an advantage for the Canadian economy. And if our abundance of water has almost been taken for granted, Canadians today regard it as a strategic resource, much more so than oil and gas. This finding is startling.

Thinking of our economic future, oil and gas are obviously a critical resource. But Canadians clearly regard water as their most important resource, even in the Atlantic and the West, where oil and gas are huge in the economy.

In the Atlantic, 31.3 percent saw oil and gas as the most important resource for the future, while 45.1 percent thought fresh water was most important. The fisheries came in third in the Atlantic at 12.7 percent, the only region of the country where they didn’t rank last among the four resources listed in our interviews.

In the West, 26.7 percent saw oil and gas as our most important resource for the future, while 60.9 percent chose water. These western numbers are closely in line with the national average.

Not only do Canadians regard water as their most important natural resource, they know we have it in abundance and expect governments to look after it.

When we asked Canadians who they thought should take the greatest responsibility for fresh water, half of them, 49.1 percent, said all levels of government — federal, provincial and municipal.

But among the other half, nearly three times as many respondents, 29.4 percent, thought the federal government should be primarily responsible, as chose the provinces, at only 11.9 percent, and just 7.1 percent chose municipalities.

On this question, there were some striking, but not surprising, regional variations. In Quebec, only 5.6 percent thought the federal government should be responsible, while 11.9 percent saw water as a provincial responsibility, only 5.1 percent saw it as a municipal responsibility, and an overwhelming 77.1 percent thought all levels of government should be responsible.

But in Ontario, only 9.7 percent thought of water as a provincial responsibility, while 41.9 percent thought it was a federal responsibility, 10 percent saw it as a municipal responsibility, and 34 percent thought all levels of government should be responsible.

With the notable exception of Quebec, Canadians are prepared to accept federal leadership on this issue, but would clearly prefer everyone to work together. And even Quebecers think this is bigger than Quebec. Three Quebecers in four, as opposed to the national average of one in two, want all governments to cooperate on this issue. Quebecers clearly understand that even within the federation, they have shared boundary water issues with Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Ontario.

When we asked Canadians their “greatest concern regarding fresh water in Canada,” water pollution was clearly their top preoccupation at 39.8 percent, while waste and overconsumption was at 22.1 percent. The quality of drinking water was the top concern among 18.5 percent, while 17.2 percent chose bulk water exports from among the four options mentioned in our interviews. Canadians are most concerned about pollution and conservation of fresh water. And while they may not be in favour of bulk water exports, they are not very concerned about it.

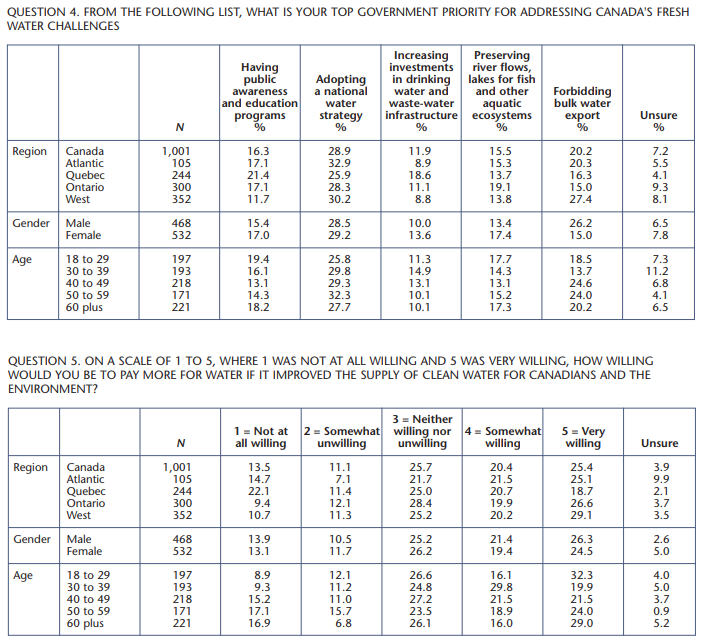

But when we asked Canadians what they thought should be the “top government priority for addressing Canada’s fresh water challenges,” “forbidding bulk water export” came in second from among five suggested priorities, at 20.2 percent, second in importance to “adopting a national water strategy,” which ranked first at 28.9 percent.

In a sense, what Canadians want here is a national water strategy that includes the forbidding of bulk water exports.

Public awareness and education ranked third at 16.3 percent, preserving water flows and aquatic ecosystems ranked fourth at 15.5 percent, while only 11.9 percent thought government should increase investments in water and waste-water infrastructure.

But when we asked Canadians whether they would be willing “to pay more for water if it improved the supply of clean water,” fully 25.4 percent said they would be “very willing,” and another 20.4 percent said they would be “somewhat willing.” Only 13.5 percent said they would be “not at all willing” to pay more for water, and just 11.1 percent said they were “somewhat unwilling.”

In other words, with varying levels of willingness, nearly half of Canadians are prepared to pay more for fresh water, if governments can guarantee an improved supply.

Canadians are very engaged on the issue of fresh water. Not only do they regard it as by far our most important natural resource, a somewhat surprising finding when the importance of oil and gas to our economy is considered. They also regard it as important to the Canadian identity — they don’t mind being seen as “drawers of water,” for they see themselves that way.

And when you look inside the numbers of this Nanos-Policy Options poll, you see something else. Canadians not only see water as critical to their future and a part of their identity, they also see Canada’s abundance of fresh water as a matter of sovereignty.

Photo: Shutterstock