If not for the coronavirus, there would be a women’s metropolis within the metropolis of New York this week, its hotels and restaurants filled with the 12,000 civil society participants of the UN Commission on the Status of Women conference. The commission, however, has indefinitely postponed the event, which was also meant to mark the 25th anniversary of the landmark Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and its declaration and platform for action.

What a shame, this postponement. The late feminist icon Betty Friedan said of the 1995 conference that the “meeting was the message,” and so it was. You put together tens of thousands of women to agitate for change, and change is bound to occur – within their global causes but also for them individually.

Back in 1995, I was a journalism student at Concordia University and a brand-new, part-time reporter at The Canadian Press. My friend Carol McQueen (today, Canada’s ambassador to Burkina Faso) and I were co-news editors at Concordia’s newspaper, The Link, and we had this crazy idea about going to cover the conference in Beijing.

Over the months, we fundraised from every possible source, and finally scratched together the money to make a go of it. I also set up a freelance gig with the now defunct weekly Montreal Mirror.

The Conference was being held only six years after the Tiananmen Square Massacre. China was a very different place at the time, in the very early stages of major economic reforms. Here it was, “welcoming” tens of thousands of equality activists, and also media from around the world. China was under the global spotlight in a way it had never been before, and we, too, were being scrutinized. Most of us were surveilled in some way during the conference, and at the massive NGO Forum on Women of 30,000 civil society delegates that was held before the official conference. Just a few months before the opening of the forum, the Chinese government abruptly moved it to the woefully underprepared town of Huairou, about 50 kilometres away from Beijing. The Chinese government and the Vatican had also tried to block certain women’s groups from attending.

In Huairou, the infrastructure was rough. Rainy weather turned the grounds into a Woodstock-esque mud pit. Women with disabilities relied on others to help hoist wheelchairs up stairs or into tents. Tibetan exiles from around the world battled with Chinese police on a daily basis. The LGB tent received constant visits from authorities, and its pamphlets would go missing.

Still, the energy at the forum was electric. There were women from every corner of the planet there, picking their way around puddles and collapsing tents to attend speeches and panels, and rallying behind those who had the most harrowing stories to tell – of genital mutilation, domestic abuse, enslavement, wartime rape, and sexual orientation conversion therapy.

One day, on the morning shuttle bus from Beijing to Huairou, I sat beside Betty Friedan herself (had it happened today, of course, I would have had a selfie). Other feminist celebrities were there – Gloria Steinem, Sally Field, for example. It was in Huairou that then-First Lady Hillary Clinton made her first major international speech.

But it wasn’t the big names that made the impression, it was the dozens of delegates who we interacted with.

There was Regina Cammy Shakakata of Zambia, who was a pioneer in getting women online in Africa. Shakakata, who has since passed away, worked at the conference press centre helping delegates get online as part of the Association for Progressive Communications. Clogged inboxes wouldn’t be a thing for many more years.

I met Satoko Watanabe, who went from activism at her kids’ school, to running successfully for a seat in the Kagawa prefecture in Japan. We talked about women’s representation in parliaments around the world – at the time, under 10 percent internationally. Years later, Watanabe would help create camps for children affected by the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

The stories stayed with us.

Lifelong Tibetan rights activist Carole Samdup was another Montrealer who attended the conference, part of an international group of exiled Tibetan women who made it to Beijing and managed to capture the attention of international media around human rights abuses.

In a recent phone conversation, Samdup told me that while the conference might not have discernibly improved the human rights situation inside Tibet in the long run, it did have lasting impacts. Their group made lasting connections with other NGOs around the world, gained expertise in dealing with international officials and journalists, and were able to individually influence many fellow delegates. Samdup says she still meets people who remember the Tibetan delegation in Beijing.

“Many of those people have gone on to be something in their lives and carry the story with them,” Samdup said.

Twenty-five years after the Fourth World Conference on Women, in February 2020, I found myself once again at a women’s gathering. This time, a leadership academy for women in the media put on by the Poynter Institute. Two very different contexts, of course, but in the end the personal impact was similar.

When women get together for professional, social or activist reasons, there is an easiness and a feeling of empowerment. Perhaps it is because we spend much of our lives living within larger societal institutions that were originally built for men – our legislatures, newsrooms, factory floors, universities, boardrooms, and offices. Together, we temporarily create a space that is resolutely ours, and where we can imagine different ways of living and working. Within this space, we can hopefully also understand how race, colonialism, disability, mental illness, sexual orientation, income level and religion specifically impact the trajectory of each other’s lives. In these gatherings, we are seen.

Critical masses of women, such as the group in Beijing in 1995 and the #MeToo movement, are difficult to ignore. The late American women’s activist Bella Abzug said in a plenary speech in Beijing that a “global movement for democracy,” had been born with the adoption of the final declaration by 187 governments.

“It is an agenda for change, fueled by the momentum of civil society, based on a transformational vision of a better world for all,” Abzug said. “We are bringing women into politics to change the nature of politics, to change the vision, to change the institutions. Women are not wedded to the policies of the past. We didn’t craft them. They didn’t let us.”

Alas, the struggle for gender equality, women’s health, education, and personal security continues, and advancement is not happening nearly as quickly as we had all hoped when we got together in Beijing 25 years ago. Around the world, women’s gains are being threatened or rolled back. As Gabrielle Bardall has written, the world’s autocrats have either been using feminist gestures to undermine democracy, or have been overtly targeting women – especially online.

Canada’s own assessment of the progress it has made since 1995 notes a number of persistent challenges, including underrepresentation in leadership roles, the gender wage gap, and high rates of gender-based violence. There are new concerns, too – that women are being shut out of the new technology-oriented world of work.

Despite all of this, I have to believe the imprint the conference made on the tens of thousands of attendees is important. Hopefully, once the threat of COVID-19 has passed, a new generation of equality seekers will be able to come together en masse for the UN conference. Sometimes it is in the act of gathering that we can both command wider attention, but also recognize our own personal potential to affect change.

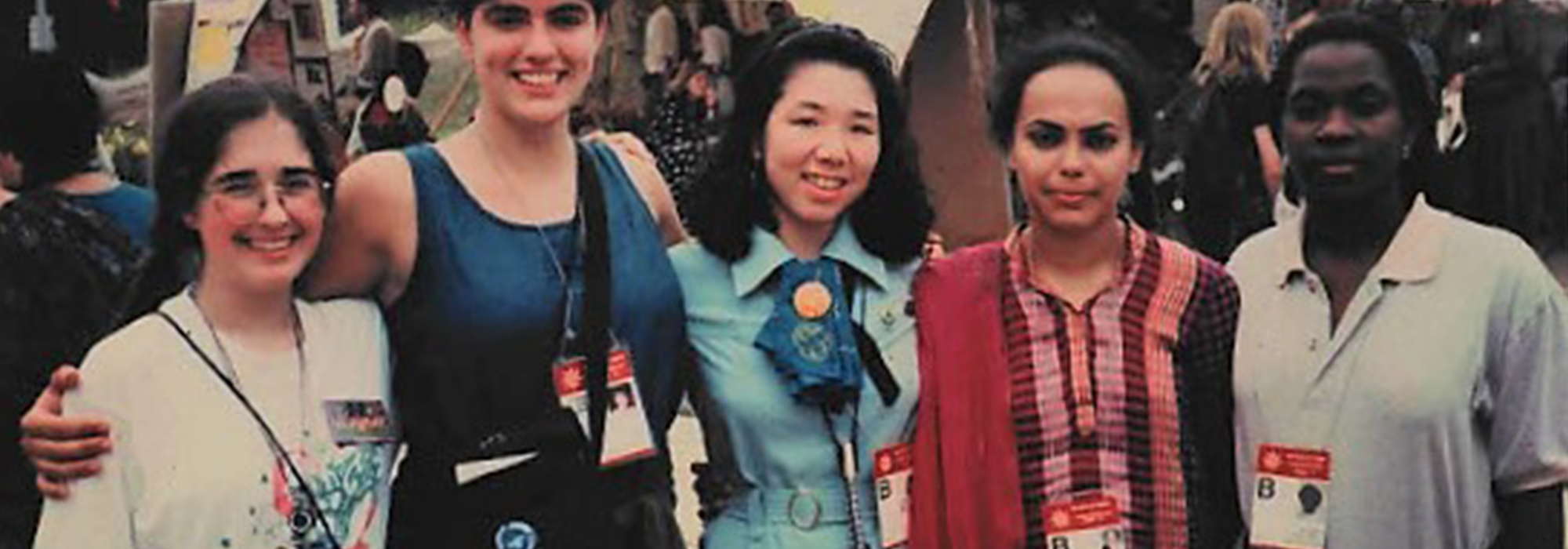

Main photo: Delegates at the NGO Forum on Women, September 1995. By Jennifer Ditchburn.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.