(This article has been translated into French.)

Let’s be honest, it’s difficult to feel an emotional connection to the number 150. There’s nothing particularly personal about it. Canada’s sesquicentennial marks the country’s age and accomplishments (and failings), but it doesn’t mark our own individual journeys as citizens. (Maybe that’s why I often notice the Terry Fox statue when I walk down Wellington Street, but the statues of long-dead prime ministers fade into the landscape.)

When I think instead about the 50th anniversary of Canada’s centennial year — that’s something that resonates.

I am part of the generation that emerged from the postcentennial period, sons and daughters of the baby boomers.

Those years after the centennial year were significant for many of us who had roots in the shift under Lester B. Pearson to allow more immigration from non-European countries. Some among us were part of the movement of refugees into Canada from places like Chile, Uganda, Vietnam, (see Judy Trinh’s excellent column) and Cambodia.

My mother immigrated to Montreal from Guatemala in 1969, after a stint a few years earlier as a student in Pembroke, Ontario. I like to hear her stories of sharing a cramped apartment with four other Latin American women, eating peanut butter on crackers when money was tight. They made a go of it in the city as secretaries, nannies and students. (Mom later met my anglo-Montreal father at a class at McGill.)

When I think about being Canadian, I cannot untangle it from the Central American roots. I think about photos of my Ditchburn grandparents and my De La Cerda grandparents visiting each other in Canada or in Guatemala. To this day, my Ditchburn relatives still use tablecloths made of Guatemalan fabric when company comes over, and my Grandma Lois Ditchburn’s paintings (she was a visual artist) hang in the homes of my De La Cerda relatives in Guatemala City. Our lives are forever woven together like that.

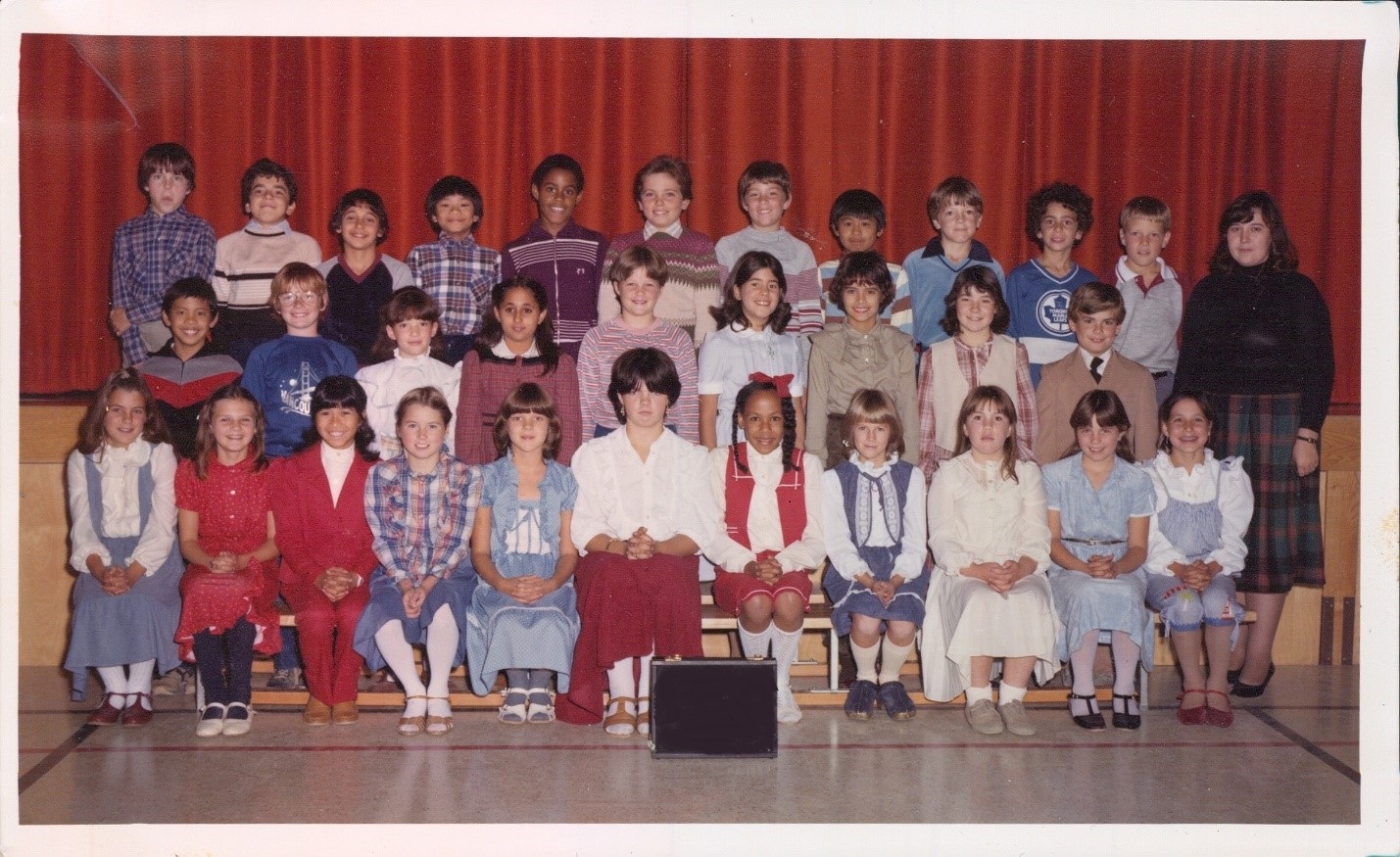

Our family moved around a lot while I was at grade school, living in Mississauga and Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario; Richmond, British Columbia; and Montreal, Quebec. Mississauga and Richmond in the 1980s had particularly fast-changing demographics.

In Grade 9, we took a new multiculturalism class. We were to celebrate our ethnic backgrounds — even if the wider society was often slow to share in this celebration (as my mother discovered when a knuckle-dragger behind her in the grocery checkout line told her to “go back to your country”).

But in this period of intense social change from which my generation sprang into the world — the postcentennial generation — immigration and multiculturalism represented only part of the forces driving that transformation.

Think of the Quiet Revolution, official bilingualism, the easing of divorce laws, the birth of the CEGEP system in Quebec, the legalization of birth control and the rapid increase in the number of women in the workforce.

It was only in 1969 that Indigenous people everywhere in Canada could vote. This was also the tail end of the residential school period, and the abandoning of the notorious White Paper on Indigenous affairs — the culmination of the “Long Assault,” as Trent University’s David Newhouse called it in his IRPP paper, while not the end of colonial policies.

Attaching a fixed time span for this group is tricky. Statistics Canada describes the “children of the Baby Boomers” as people born from 1972 to 1992, and then more specifically “Generation X” as 1966-71, and “Generation Y” as 1972-92. The economist and writer David Foot, author of Boom, Bust and Echo, defines the “baby bust” as 1967-1979 and the “echo boom” as 1980-1995. (Foot has also said that “Generation X” is actually the tail end of the baby boom in the early 1960s, and not the later period many people peg it at.) I would make the case that there is a certain ethos attached to Canadians born from around the centennial year to the early 1980s.

Whatever you call the baby boomers’ sons and daughters, we were portrayed as aimless, Central Perk flâneurs in our early adulthood, hopelessly overshadowed by the big population bubble ahead of us in the workplace.

And yet, the slackers of yesterday are today’s leaders, including CEOs (for example, Shopify’s Tobias Lütke), broadcast hosts (CBC’s Rosemary Barton), senior public servants (Chief Trade Commissioner Ailish Campbell), chiefs (Grand Chief Derek Nepinak of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs) and social activists (Naomi Klein).

Look at our Parliament — the Mr. Dressup generation has now infiltrated 24 Sussex (Justin Trudeau, born 1971) and Stornoway (Andrew Scheer, born 1979). Among the candidates to lead the NDP, Guy Caron, Jagmeet Singh and Niki Ashton probably cut a rug to C&C Music Factory at some point. (See Singh’s totally awesome Gen-X-tinged political leadership ad featuring Roch Voisine cassettes.)

The firm that tracks emerging trends among media company Viacom’s viewers recently completed an international study, Gen X Today, using the range of people currently aged 30 to 49. The study argues that this generation is “behind many recent socio-cultural transformations often associated with Millennials.”

“Gen X are trailblazers,” write the authors of an article about the report. “They’re leading movements to achieve equality for people of all races, genders, and sexual orientations. They’re driving change in our governments and workplaces. They’re the consumers with disposable income making household purchase decisions.”

(This explains why they’re making Domino Pizza commercials shamelessly based on scenes from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.)

And so, if a sesquicentennial is a moment for reflection, we might ask what role the postcentennial generation has to play as it assumes more positions of leadership after Canada 150, whether it be in the private sector, the public service, politics, or in our schools and neighbourhoods. If we allow ourselves a moment of unbridled generalizing, what do we bring to the table, and what are our blind spots?

On the positive side, we could view the generation between the boomers and the millennials as a bridge.

There’s a certain beauty in having been among the first, enthusiastic adopters of new technologies. There was that excitement in the early 1990s of sending early e-mails through the internal university system, or entering scribbled contacts into a Palm Pilot (maybe while listening to the Stone Temple Pilots?). We love our tech, but we also remember those salad days when call waiting wasn’t even a distraction (Canadian writer and thinker Douglas Coupland talks about missing his pre-Internet brain). This analog/digital perspective might provide a dose of prudence as the world hurtles toward an unknown future filled with self-driving cars, artificial intelligence devices and even more pervasive social media.

Many people born in the years around the centennial year had close relatives who fought in the world wars or who were affected by the Holocaust. (My grandfather was a Royal Canadian Air Force navigator in the Second World War.) In the not too distant future, we will be the last generation to have this direct connection with those dark chapters, so we carry the responsibility of keeping their memory alive.

And there were the wars at home through the residential school system, and so many other state-sanctioned indignities against Indigenous people, policies that were the source of intergenerational trauma. The generation of Indigenous people that came after the residential schools closed is part of what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission called the “communities of memory.” David Newhouse’s view is that a new Aboriginal society is emerging, “imbued with what I call ‘postcolonial consciousness’ — that is, an awareness of the history of the Long Assault and its legacy, a determination to heal from its effects and a desire to ensure that it does not happen again.”

For women, the suffocating gender roles and overt sexism of the past haven’t totally disappeared, but their grip on our individual potential has been wrenched loose. We’ll be damned if there’s any backsliding. There is a fierceness among us to ensure that the words “manel” and “glass ceiling” don’t enter into the lexicons of our daughters.

On the negative side, some of us may also be limited by the time in which we grew up.

I think I’m safe in saying that most non-Indigenous people of this postcentennial generation grew up largely ignorant of what was happening in residential schools and First Nations communities across the country. Speaking personally, the curriculum in grade school had some paltry units on the voyageurs, longhouses and the death of Jean de Brébeuf (yeah, Catholic school), but little else of substance about Indigenous culture or history.

During high school and CEGEP, we lived a short drive or boat ride from Kanesatake and Kahnawake, but it might as well have been thousands of kilometres away. Informing ourselves and working toward reconciliation in concrete ways is a national imperative, but not necessarily one that all will embrace.

Depressingly, we can’t always rely on our generation to push the cause of gender equality once they are in positions of power (see the recent controversy around Uber’s “bro-culture,” or the paltry number of women on TSX-listed boards). Social media has become a powerful new source of misogynistic voices.

And we have a tendency to get caught up in the political discourses of yore, a sort of intellectual rut that might last decades.

On this point, it’s disappointing to hear Justin Trudeau close the door on the possibility of any discussion of the Constitution. The provincial, federal and Indigenous actors who would be involved in constitutional talks today are completely different — Canada is different. Consider that at the time of the Meech Accord and Charlottetown Accord talks, there was not a single woman among the provincial premiers. What message does it send to younger Canadians now that we are not open to exploring the most challenging of our national conversations?

The contours of the debates of our parents’ time are, well, getting old, like our parents. I think of the National Energy Program chestnut, raised most recently by Saskatchewan cabinet minister Scott Moe to argue against carbon taxes. Can we get a new frame for the debate, please?

I like the words of Alika Lafontaine of the Indigenous Health Alliance, who challenges the limited expectations that society places around the outcomes for Indigenous people: “Expectations don’t take decades to change. They change in a moment.”

This Canada Day, I’m going to enjoy checking out the luminous new reconfiguration of the centennial-era National Arts Centre, whose austere brutalist structure is now encased in glass to let the sun in and attract a new cohort of patrons. Hey, it’s a bit like the generation that was hatching back around 1967 — let’s hope that while being firmly grounded in the past, we’re also constantly renewing and facing outward to the future.

This article is part of the Public Policy toward 2067 special feature.

Photo: Montreal during Expo 67. THE CANADIAN PRESS/stf

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.