(This article has been translated into French.)

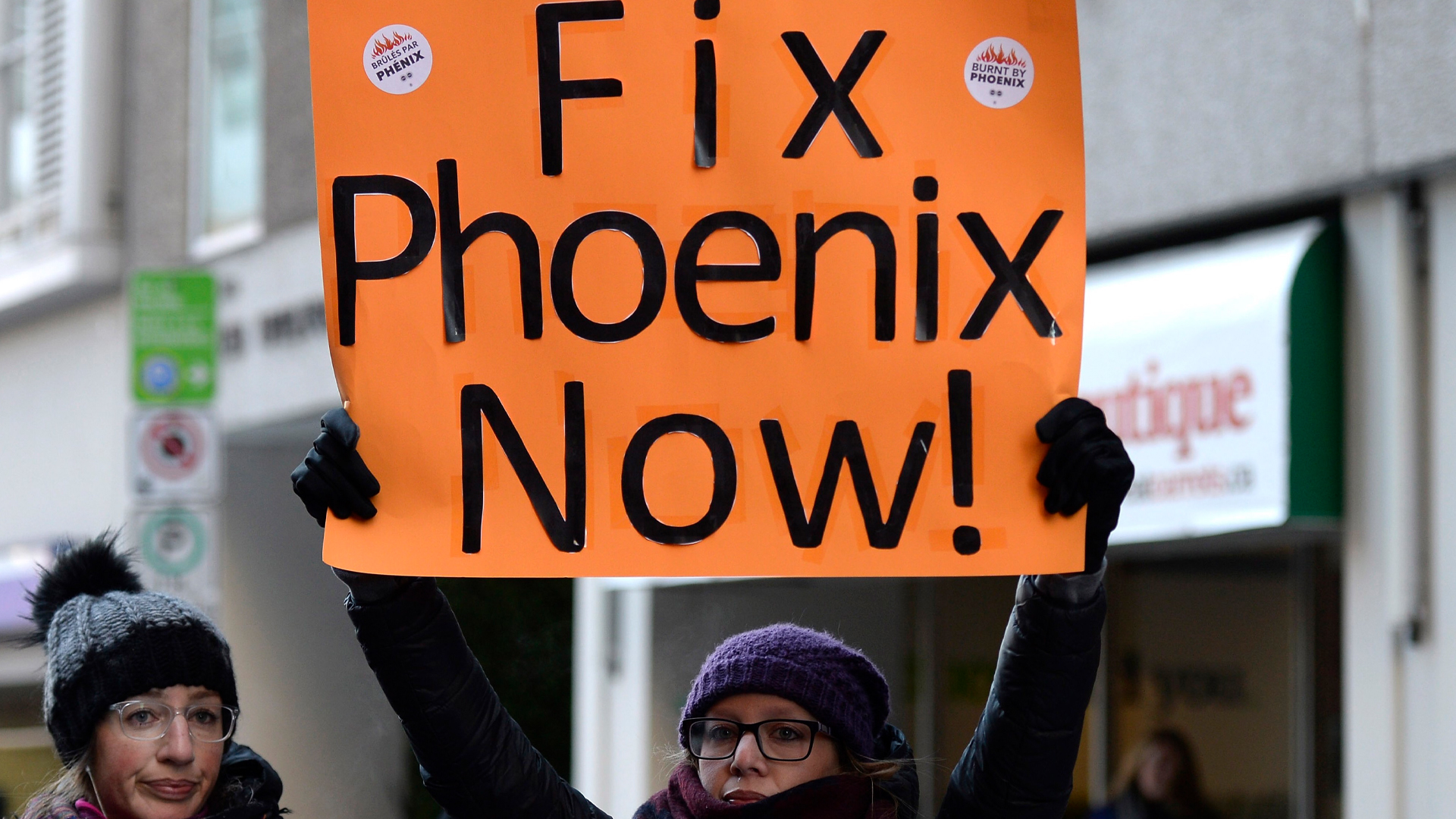

Federal government departments are approaching an important anniversary with the infamous Phoenix pay system and are now in a race to recover thousands of salary overpayments to public servants before they run out of time.

The troubled Phoenix has churned out nearly $3 billion in overpayments to employees since it went live in February 2016. Nearly every public servant has been affected by Phoenix’s technical glitches, human errors or bad data in processing paycheques. Thousands were overpaid, underpaid or not paid at all over the past six years.

Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), the government’s paymaster, estimates that Phoenix issued overpayments to 337,000 employees over the years. So far, 222,000 of them have paid back about $2.3 billion. The remaining 115,000 owe about $552 million – but there could be more in the backlog.

The biggest outstanding payment is $300,156, but more than two-thirds of them range between $100 and $5,000.

In recent months, however, the focus is on the people who were paid too much by Phoenix in its first year of operation. By law, the federal government has six years to collect salary overpayments from employees – after which they become unrecoverable and are written off as debt.

That means departments must find any remaining overpayments, recover the money or at least initiate steps for repayment before the six-year statute of limitations expires in February.

Pay specialists combed files for 2016-17, including the thousands sitting in the backlog, and found about 21,000 outstanding overpayments.

Letters flagging the overpayments were sent to the 21,000 employees – many of whom claimed they had no idea they were overpaid. The employees were asked to acknowledge the overpayment in writing and were offered flexible options for repayment. If the letter isn’t acknowledged within four weeks, the money will be clawed backed from their pay.

“This is about exercising due diligence, stewardship. This is taxpayer money, owed to the Crown, and we have to make sure taxpayers aren’t screwed,” said one long-time bureaucrat who is not authorized to speak publicly.

This last-minute race against the clock is not sitting well with public service unions.

They argue overpayments should have been fixed long ago. It’s unfair to demand employees acknowledge debts that may be coming out of the blue.

Federal public service leaves work-from-home decision to departments

The government letters explain what record searches found, amounts owing and what caused the overpayments. But some public servants, frustrated and distrustful of Phoenix, complain they have no way to verify these details six years later. Some claim they have already repaid any amount owed.

“The truth is, there hasn’t been a single pay period without issues since the Phoenix fiasco began in 2016. So, it’s absolutely outrageous that the government now wants to claw money back from employees,” said Chris Aylward, president of the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). “In most cases, these overpayments come as a complete surprise to our members, and many have no way of confirming if they even owe money at all.”

What further infuriates the unions is that this race to meet the six-year limitation could continue every year until Phoenix is replaced.

“Unfortunately, this is just the beginning. This process will continue each year as Treasury Board races against the clock to meet the six-year threshold of all overpayments,” said Aylward.

“Public service workers who’ve suffered so much already at the hands of Phoenix deserve better, and their ordeal won’t be over until the government puts in place a pay system that pays them accurately and on time, every time.”

PSPC, however, doesn’t expect to be up against the six-year limitation year-after-year. Once the backlog is eliminated, with all files caught up and errors fixed, overpayments will be corrected as they come up. It’s unclear when that will happen but the current target is this year.

PSCA opposes the repayment plan but also advises its members to pay up if they owe money. If the members are unsure, they should ask for more proof. Some could be waiting for money owed to them because of another Phoenix gaffe and, in that case, the union suggests employees ask for that money before repaying the overpayment.

For those who were assured their pay was correct or were unaware of an overpayment the union suggests adding “I should not have to repay these amounts” in their responses.

The government struggled with overpayments using its old pay system, but they exploded with Phoenix. They were a nightmare for the first two years. By the end of 2017, PSPC figured employees owed $246 million in overpayments.

The errors overwhelmed the new pay centre in Miramichi, N.B. Swamped with files, most of the pay specialists were new to the job and there weren’t enough of them. Overpayments piled up because the first priority was getting paycheques out and money to people who were underpaid or not paid at all.

Most overpayments were created when acting assignments, promotions, terminations or various types of leave weren’t entered on time. Employees ended up getting paid too much or for too long. Those moving to new departments could sometimes receive two salaries. In some cases, term employees or retirees continued to be paid even after their positions were terminated.

Phoenix was built to operate in real time, so a late transaction was its Achilles heel. This was a huge cultural change for a public service that had always sent in transactions late or after the fact.

Take for example what the PSPC calls “administrative overpayments” with acting pay – the biggest culprit. This is extra pay employees receive when they fill in for bosses or other colleagues. A late acting-pay claim not only generated an overpayment but could cascade into a host of other errors – union dues, bilingual bonuses or benefits – that needed to be fixed manually.

The government has since spent more than $1.3 billion to fix Phoenix and a large share of that was for staffing, which has quadrupled. Overpayments still happen, but there have been fewer of them because of the various changes implemented over the years. Acting pay snafus were fixed in 2020.

However, overpayments were a flash point for unions because of the tax implications and the burdensome collections process. The government changed tax and repayment rules to help employees cope with the complications created through no fault of their own.

The government put off recovering overpayments until employees’ pay files were fixed and they were paid correctly for three consecutive pay periods. They could then make repayments in instalments, as a lump sum or through deductions from pay cheques. This flexibility is still on offer for the 21,000 who acknowledge the debt, but not for those who don’t.

Phoenix is the biggest public management disaster in the bureaucracy’s history. On top of the cost, the government has paid more $560 million in damages to compensate employees for emotional and financial hardship.

Phoenix remains the government’s pay system until its replacement, dubbed NextGen, is completed. A pilot is underway, but the new system is still years away.

This article was produced with support from the Accenture Fellowship on the Future of the Public Service. Read Kathryn May’s previous articles on the future of the public service.