(Version française disponible ici)

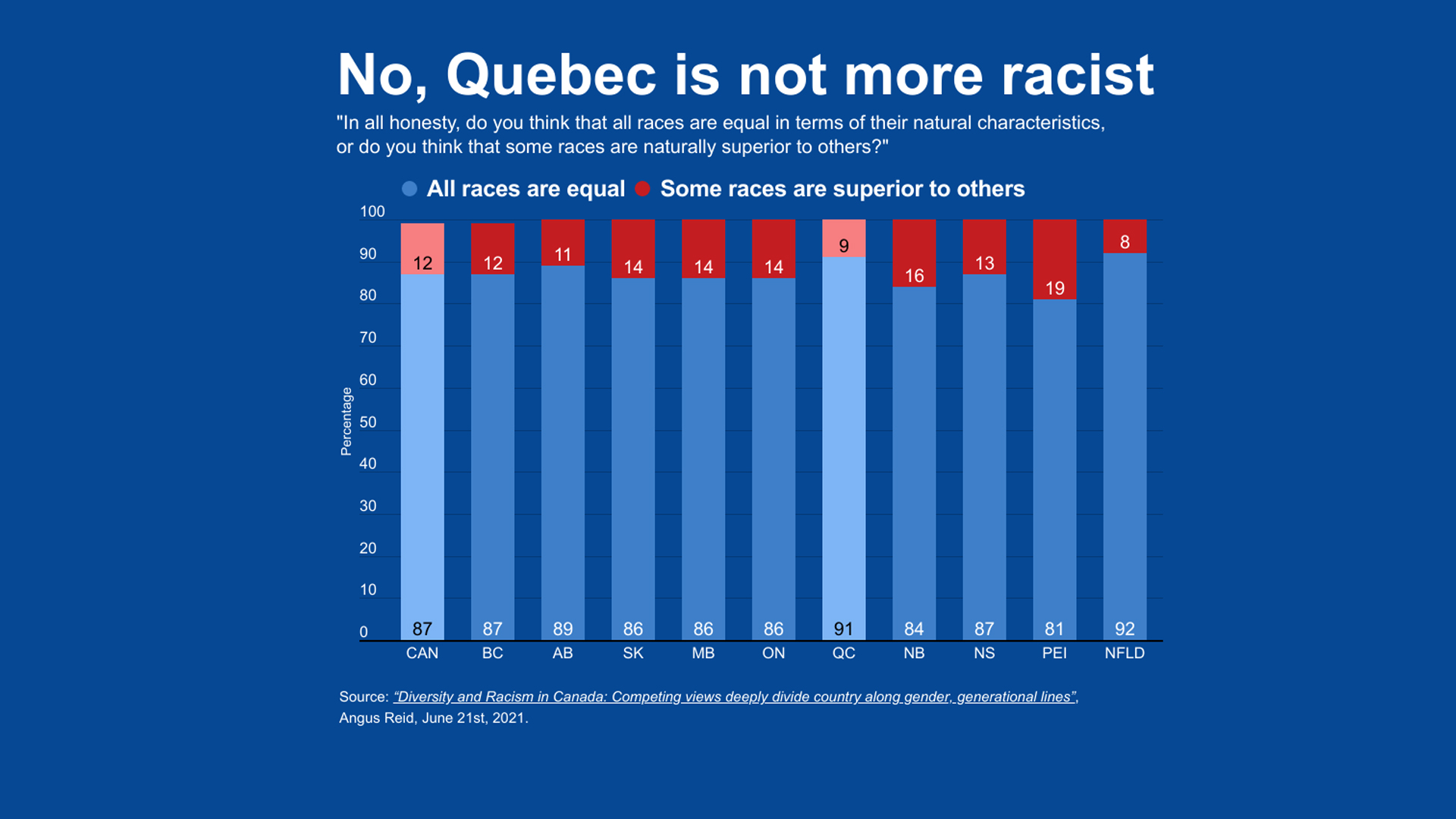

The number is nine. That’s the percentage of Quebecers who believe some races are superior to others. They, along with other Canadians, were asked this straightforward question by the Angus Reid Institute and the University of British Columbia in 2021: “In all honesty, do you think that all races are equal in terms of their natural characteristics, or do you think that some races are naturally superior to others?”

Nine per cent may seem high, but compare it to Ontario, Saskatchewan and Manitoba with a rate of 14 per cent. There is a spike of 19 per cent in PEI (this may be a sampling error) and lows of 11 per cent in Alberta and eight per cent in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Interestingly, one finds that 13 per cent of Indigenous people believe in the inequality of races and 18 per cent of non-Caucasian/non-Indigenous – double the Quebec number.

How can we possibly square this result with the mere existence of Quebec’s secularism law, known as Bill 21, and the apparent consensus outside Quebec that citizens there are closed-minded? The answer, as Justin Trudeau explained the other day, is Quebecers relation to religion, especially with the misogynistic aspects of the Catholic religion of yesteryear and, these days, Islam.

That is why this same Angus Reid Institute poll found what every other poll will tell you: a much bigger slice of Quebec opinion has negative views of religions as a whole and of Islam in particular. Angus Reid reports that whereas 25 per cent of all Canadians feel “cold” towards Muslims, the chill reaches 37 per cent in Quebec. Still in minority territory (63 per cent feel warm towards them) but a significant difference.

Since support for the secularism bill, which bans the wearing of all religious signs for civil servants in authority, hovers around 65 per cent, there are simply not enough Quebecers who dislike Muslims to account for that great a number. Clearly, other variables are at play and racism is not one of them.

In fact, Canadian pollsters regularly find Quebecers more tolerant on a range of issues than other Canadians. Ekos found in 2019 that 30 per cent of Quebecers believed there were too many members of visible minorities among immigrants. That is awful. But this level rose to 46 per cent in Ontario and 56 per cent in Alberta. And among visible minorities, 43 per cent felt there were too many visible minorities among immigrants. In short, Quebecers were less intolerant of immigrants of colour than Canadians as a whole and citizens of color themselves.

But these are opinions. What about actions? Hate crimes were more numerous in Ontario than in Quebec per capita in 2019, 2020 and 2021, the year in which there is the latest available data. The Montreal police reports that in 2020 and 2021, the first years of application of the law on secularism, the number of hate crimes related to religion was down 24 per cent. Sure, with the pandemic, there were fewer opportunities to meet and hate each other. Yet they also had a pandemic in Toronto and there, according to the Toronto Police 2021 Hate/Bias Crime Statistical Report, religious hate crimes increased by 16 per cent over the same period.

How about discrimination in employment? 2021 Statistics Canada data show that immigrants in Quebec have an employment rate greater than workers born in Quebec (at a ratio of 107 per cent) whereas the opposite is true in Ontario (a ratio of 95 per cent). The gap is greatest for women, with a ratio of 102 per cent employment in Quebec versus 91 per cent in Ontario, probably a result of Quebec’s far reaching daycare program. The same is true for members of visible minorities, whose rate of employment is equal to that of the rest of Quebecers, better than the 95 per cent level in Ontario. Simply put, as an immigrant or a BIPOC, your chances of getting a job is higher in Quebec than in Ontario, especially if you are a woman.

The recent October 2022 Quebec election was remarkable for one barely noticed achievement. For the first time, it delivered the same proportion of elected members from visible minorities, (12 per cent) than their share of the electorate and the same rate (20 per cent) of members of non-French and non-English origin. A perfect score. In Ottawa, Parliament still falls short of its goal of representing 25 per cent of visible minorities, having reached only 15.7 per cent. In Ontario, with 30 per cent of minority population, the recent parliament counts 23 per cent representation.

None of these numbers are new, but I bet you are reading them here for the first time. Why? Simply because they are so counter-intuitive that few people outside Quebec look for them. Or when these numbers are encountered, they are treated as outliers that surely do not represent reality.

Yet going back in time, Quebec has reached achievements on race significantly before others on the continent. For example, the August 1 commemoration of the British Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 is problematic in Quebec because it ignores the fact that slavery had already been abolished there for 30 years. In Upper Canada, MPs had voted in 1793 to abolish slavery but grandfathered the “property” of current slave-owners. Slavery thus persisted until 1820. The British 1833 act compensated slave-owners for the “loss” of their property.

Quebecers had none of that. Open-minded judges started declaring slavery illegal in Quebec as early as 1798, without delay or compensation. It disappeared completely in very short order, as told by Frank Makey in his seminal Done with Slavery: The Black Fact in Montreal, 1760-1840 (McGill-Queen’s Press). “The way in which slavery was abolished in Quebec turned out to be one of the most humane and least constraining,” he writes. Slavery thus ended in Quebec 20 years before its demise in Upper Canada, 30 years ahead of the rest of the Empire and 63 years before the emancipation of Black Americans.

Jews were barred from elected office in the entire British Empire until 1858, except in Quebec. In 1832 the Assembly, with a Patriote majority (the ancestor of both the Quebec Liberal Party and the Parti Québécois) voted an act granting full citizenship to Jews, the Brits be damned.

How Quebec is building on René Lévesque’s constitutional legacy

Francophone Quebecers increasingly believe anglophone Canadians look down on them

As for relations with First Nations, in 1701 the Governor of New France and 39 leaders of First Nations gathered in Montreal for the most far-reaching peace treaty ever negotiated between settlers and First Nations in the hemisphere. That’s Nobel Peace Prize territory. In modern times, Quebec signed the first comprehensive land claim in Canada in 1975 and René Lévesque made sure the Quebec National Assembly was the first Parliament in Canada in 1984 to recognize the existence of Indigenous nations on the territory. In 2003 the Paix des Braves with the Cree nation became the gold standard for the granting of autonomy to First Nations.

Environics Institute reports that like other Canadians 44 per cent of Quebecers believe the government has not done enough to ensure true reconciliation. But there are laggards. Those who find that we have gone too far, that we have been too generous. In Quebec, 13 per cent think so. Too many. In Canada: 20 per cent. Too many and a half.

It is also interesting to note how the anti-religious sentiment of Quebecers is intertwined with the issue of residential schools. Polling firm Léger asked who was responsible for this disaster: the federal government or the Catholic Church. Obviously, the answer is: both. But the pollster forced his respondents to choose. Two-thirds of Canadians pointed to the church. Quebecers even more: 69 per cent. The more memory Quebecers have, the more they condemn the church, at 76 per cent among those over 55 years old. Quebecers also say they are more ashamed, at 86 per cent, than the high Canadian average of 80 per cent.

Surely, tons of columns can be – and have been – written on all the faults and frailties of Quebecers. I have written a few myself. Comparative arguments have little weight when the task is to fight back against discrimination, racial profiling, decades-long neglect of Indigenous communities.

They have value, however, when mainstream voices outside Quebec take a moral high ground to misjudge and mischaracterize Quebec, its citizens and its history on issues of race and tolerance.