It’s no secret that the Saskatchewan government doesn’t like the idea of a national carbon price. When Prime Minister Trudeau announced federal plans for a carbon price floor in early October, Saskatchewan Environment Minister Scott Moe walked out of a national environment minister’s meeting, and Premier Brad Wall called the plan a “betrayal.”

Fifteen days later, on October 18, Saskatchewan released its Climate Change White Paper. The White Paper is positioned as an “alternative approach to Prime Minister Trudeau’s national carbon tax.” It argues that “talk about a carbon tax and cap and trade is the wrong conversation to be having” and seeks to shift the national conversation to “one that has a global perspective and a focus on innovation.”

What follows is a brief evaluation of whether the White Paper achieves its intended aim.

- Has it proved carbon pricing to be “an ineffective way of reducing carbon consumption,” as it claims?

- Has it proved that “the negative consequences of a carbon tax for Saskatchewan employment and the provincial economy would be significant”?

- Has it provided a convincing alternative means of addressing climate change?

- Will it change the national conversation on climate action?

Is carbon pricing ineffective?

The Saskatchewan Climate Change White Paper asserts that, “carbon taxes at the rate currently being contemplated will not modify behaviour.” The carbon price being contemplated is $10/tonne CO2e in 2018, increasing by $10/year to reach $50/tonne CO2e in 2022.

Economic analysis of the British Columbia carbon tax has shown that these prices are likely to modify behaviour and reduce emissions. BC introduced a $10/tonne carbon tax in 2008. The tax increased by $5/tonne each year until it reached $30/tonne in 2012. It remains at that level today.

Summarizing several studies, Brian Murray and Nicholas Rivers find that “empirical and simulation models suggest that the (BC carbon) tax has reduced emissions in the province by between 5% and 15%” relative to a business-as-usual forecast. University of British Columbia economics professors Werner Antweiler and Sumeet Gulati confirm this finding in the transportation sector in their working paper Frugal Cars or Frugal Drivers? How Carbon and Fuel Taxes Influence the Choice and Use of Cars. Antweiler and Gulati conclude that “without BC’s carbon tax fuel demand per capita would be 7% higher, and the average vehicle’s fuel efficiency would be 4% lower.”

These results were achieved with a $30/tonne carbon tax. We can expect even greater reductions with a carbon price of $50/tonne in 2022. Saskatchewan’s claim that a $50/tonne carbon price will not modify behaviour is without empirical support.

Will carbon pricing harm Saskatchewan’s economy?

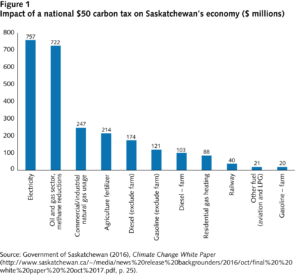

As evidence of the burden of a carbon tax, the White Paper presents a chart showing how much each sector would have to pay when the tax reaches $50/tonne (see figure 1 below). Adding the totals together, the White Paper estimates $2.5 billion worth of carbon charges in Saskatchewan.

The $2.5 billion then disappears from the White Paper analysis. But this revenue is important. Unless the Saskatchewan government burns the cash on the front steps of the legislative building, they will have $2.5 billion to spend. As Blake Shaffer points out in the Globe and Mail, the choice of how to spend the revenue should be the focus of the carbon-pricing debate.

If Saskatchewan took a fee-and-dividend approach, the government could use the $2.5 billion to send a $2,172 cheque to every woman, man and child in the province.

If Saskatchewan wanted to take a double-dividend approach, it could reduce taxes by 36 percent across the board (the total forecast tax revenue from personal, corporate, sales, and property taxes is $6.9 billion for 2016-17).

Unfortunately, many of the critiques of carbon-pricing, both in Saskatchewan and next-door in Alberta, fail to account for carbon-pricing revenues. When these revenues are ignored, citizens get a distorted view of the cost of climate policy.

Emissions-intensive trade-exposed industries

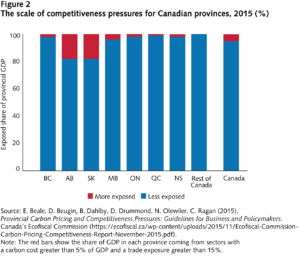

The Saskatchewan government has made the case that the province is particularly vulnerable to carbon pricing due to its export-oriented economy. In his op-ed in the Globe and Mail, Premier Wall notes, “Saskatchewan has a disproportionate share of Canada’s trade-exposed industrial sectors.” A report from Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission confirms that Saskatchewan’s emissions-intensive industries are more trade-exposed than other provinces (see figure 2 below).

Trade-exposed industries compete in global markets and cannot pass carbon costs along to their customers. The worry for Saskatchewan is that these companies will relocate to new (browner?) pastures where carbon is not priced.

Well designed policy can reduce these threats to competitiveness.

In a carbon tax regime, Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission proposes output rebates could be offered to “emissions-intensive trade-exposed” (EITE) industries. The right incentives are then in place to maintain competitiveness; companies must pay for their emissions, but are rewarded for their output.

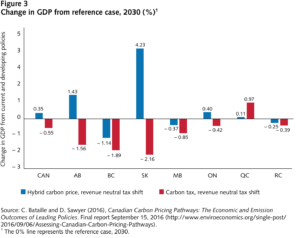

In their report, Chris Bataille and Dave Sawyer model the possibility of Saskatchewan meeting the national carbon price with a hybrid system that would include a carbon tax on buildings, transport and light industry, and a “nationally tradable intensity standard and output-based allocations (OBA) for the EITE (trade-exposed) industries.”

In their analysis, Bataille and Sawyer find that Saskatchewan would do well under a hybrid climate policy system. GHG emissions would be reduced by 33 percent by 2030, and GDP could actually increase by 4.23 percent over the reference case (see figure 3 below) if firms in Saskatchewan could beat their targets and sell credits to firms in other jurisdictions.

While international competitiveness is a concern for Saskatchewan’s trade-exposed industries, there are policy options to address this concern. Without a fuller analysis of these options, it is difficult to see how the White Paper can conclude that carbon pricing would have a “significant harmful impact” on the Saskatchewan economy.

Has Saskatchewan proposed convincing alternative policies?

The White Paper proposes shifting the conversation from GHG emissions released in Saskatchewan and Canada, which it deems “marginal,” to “the other 98%” of global emissions released outside of Canada.

This “global perspective” brings with it two noteworthy claims.

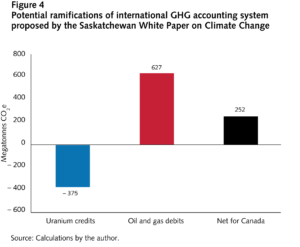

The first is that “Saskatchewan deserves credit and recognition for GHG reductions achieved through the use of uranium mined in our province.” In particular, the White Paper suggests Saskatchewan should receive credit of 375 Mt CO2e/year for exporting uranium. The assumption is that nuclear power plants fuelled with Saskatchewan uranium prevent emissions from coal-fired power plants in other countries.

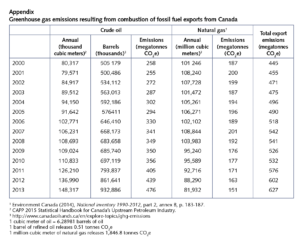

It is not clear that Saskatchewan has considered the ramifications of switching to this alternative system of international GHG accounting. If Saskatchewan receives 375 Mt of credit for exporting uranium, is Canada willing to own 627 Mt of GHGs from exported oil and gas (see figure 4 below and appendix for data sources and assumptions)?

Asking for credits for uranium opens a Pandora’s box of global GHG accounting issues that the Saskatchewan government would be wise to avoid.

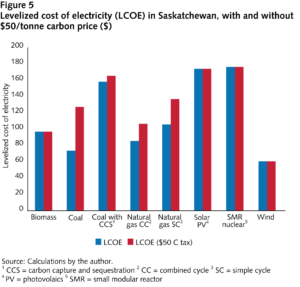

The second global claim is that Saskatchewan “can help the world clean up coal-fired electricity generation.” This is because Saskatchewan is home to the world’s first carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) facility, the Boundary Dam Carbon Capture Project. While CCS technology can help reduce global emissions from coal-fired plants, this is not really an argument against carbon pricing. As this recent MacLean’s article by Andrew Leach, Mark Cameron and Christopher Ragan argues, Saskatchewan’s CCS export strategy would actually benefit from a global carbon price. Figure 5 below shows the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) with and without a $50/tonne carbon price. As the red bars indicate, a carbon price makes conventional coal more expensive and improves the economics of CCS.

Apart from these calls for international credits and CCS technology sales, the White Paper does not present much in the way of policies for reducing provincial emissions.

Much more work is required to move Saskatchewan from White Paper to credible climate change plan.

What comes next?

Rather than changing the conversation in Canada, perhaps it is best to think of the Climate Change White Paper as the start of a conversation in Saskatchewan. As a next step, Saskatchewan could take a page from its neighbour Alberta and convene a panel of experts to propose climate policy options, model their consequences, and create their own climate leadership report outlining how Saskatchewan could reduce emissions and protect its economy. That would indeed be something to shift the national conversation.

Photo: Andrey Yurlov / Shutterstock

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.