In the June-July election issue of Policy Options, Scott Reid wrote a piece entitled “On the Long Road Back from Third Place, Liberals Need to Play the Long Game.” I agree that it could be a long game. What surprised me, however, was that almost all of Scott’s focus was on the process, machinations, tasks that needed to be accomplished in order to regain power; on membership, on fundraising, on infrastructure, on process. Only three-quarters of the way in, and with only one paragraph, does Scott suggest that there “must be an explicit effort by Liberals to capture clearly what they stand for and what they uniquely offer to Canadians.” After that, he offers only vague words such as “centrist,” “balance” and a nod to “a belief in a strong central government.”

I agree that much of that work is needed. But which comes first? The Liberal Party — any party — will have trouble wooing members or raising money without being able to say what it stands for, and how it differs from the alternatives. Yes, there are significant structural changes needed within the Liberal Party. But fundamentally, the party itself, and then Canadians, need to know where it stands, and what it stands for. Yet the Liberal Party, in its current form, isn’t sure.

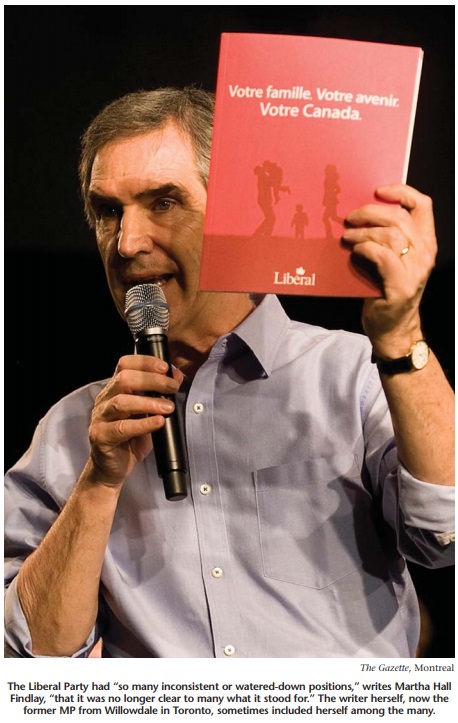

During the recent 2011 federal election if you had asked anyone on the street, in a shop, in a university classroom, in a newsroom — if you had asked anyone during that time what the Liberal Party stood for, that person would have been hard-pressed to answer. Even I, a former candidate for the leadership of the Liberal Party, a Liberal MP for several years, holder of several Liberal shadow cabinet positions and a Liberal candidate for re-election in that same election — even I could not answer that question. I knew where I stood, but I could no longer answer with any certainty for the party. I honestly wasn’t sure. No wonder we didn’t resonate with voters.

The biggest challenge for the Liberal Party — one that must be tackled before trying to woo more members and raise more money — is determining and defining what the Liberal Party actually stands for.

Yes, of course, we all said that we were the “progressive centrist” alternative, that we were fiscally prudent, economically reasonable yet focused on social justice. But these are vague generalities. There are many people who brand themselves with the word “liberal” and the word “centrist,” many within the Liberal Party itself, who have very, very different views about significant policies, yet all believing that they fall within those descriptions.

Canadian voters rightly wondered what that really meant — it certainly wasn’t clear from the inconsistent, sometimes conflicting positions the Liberal Party was taking, and had taken, on various issues.

What happened? After all, in the 1990s and earlier 2000s Canadians saw the Liberal Party as economically savvy, responsible and firm, and at the same time as a strong defender of social justice and human rights. It had developed the policies and voting record to prove it.

That reputation took time and effort to achieve. The GST, the FTA with the United States, NAFTA — when these were being debated in the 1980s, some Liberals supported them, but many did not, and the Liberal Party, officially, was cautious and protectionist. But there was dismay all across the country at the size of the debt and annual deficit that had arisen under the Conservatives. With Jean Chrétien as prime minister and Paul Martin as finance minister the Liberal Party took action, responding to what seemed broad consensus support in the country for deficit slaying, debt reduction, economy-driving lower corporate and personal income taxes. Having promised to “axe the tax” in the 1993 election, Chrétien and the Liberal Party came around to clearly supporting the GST as a more appropriate form of taxation. Eliminating the deficit, paying down the debt, lowering other taxes, supporting free trade and encouraging competition and investment, the party proved, through its actions, not just words, that it was strong and economically responsible. At the same time, many Canadians were concerned about some of the more conservative social policies espoused by many Conservatives. Here again the Liberal Party proved itself on social justice, among the most significant policies being the Party’s position on same-sex marriage. On the one hand, the Liberal Party seemed to “get it” economically, ultimately supporting free trade, confident of Canada’s ability to compete in an open and increasingly global economy, understanding the need to help create a strong economic environment and, with that, encouraging business to do what business does best. On the other, the Liberal Party showed a strong sense of social justice, human rights and equality of opportunity. And internationally. The Liberal government, which had promoted the Land Mines Treaty and Responsibility to Protect, stood its ground on international legal principles and refused to participate in the invasion of Iraq. All told, by the time I entered federal politics in 2004 the Liberal Party was the obvious home for Canadians with strong views on Canada’s fiscal realities, economic opportunities, social justice and Canada’s role in the world. It was the obvious home for me.

Or so I thought.

Not long after I joined the party in 2004, but most glaringly after the 2006 election, the Liberal Party that I thought I knew had lost that clear sense of direction. There was no clear leadership — and no consistency on policy. Liberal MPs were voting in all directions, saying all sorts of things, taking all sorts of positions — sometimes quite inconsistent with some of the basic economic and social policy directions I had understood to be “Liberal.”

Not long after I joined the party in 2004, but most glaringly after I was elected in early 2008, the Liberal Party that I thought I knew had lost that clear sense of direction. There was no clear leadership — and no consistency on policy. Liberal MPs were voting in all directions, saying all sorts of things, taking all sorts of positions — sometimes quite inconsistent with some of the basic economic and social policy directions I had understood to be “Liberal.”

Indeed, in recent years, it hasn’t been clear which direction the Liberal Party has been taking on any number of issues. The party has changed course several times, leaving people wondering where it stood. Worse, it appears that the Liberal Party has moved strongly toward the NDP on economic issues, and oddly enough, toward the Conservative Party on social issues. No wonder we lost so badly in the last election — this is exactly opposite to where the majority of Canadians want Canada to go.

Here are some examples.

On social justice: For many years, reproductive choice for women was a fundamental tenet of the Liberal Party. There is no question that abortion is a tough issue; my point here is not to debate the issue itself or make any moral comment on “right” on “wrong” (we all have our opinions and I respect that). My focus is rather the uncertain position of the Liberal Party. Full reproductive choice for women was something the Liberal Party had fought for and stood for. Last year, the Liberal Party put forward a motion in the House of Commons on the funding of maternal health services, including abortions, in developing countries. Yet enough Liberal MPs voted against the motion to defeat it. Totally aside from the embarrassment of having Liberal MPs defeat a Liberal motion, it begs the question of where the Liberal Party stands on choice. The NDP had no trouble making its position clear. Nor did the Conservatives. The Liberals had become clear as mud.

On crime: For years now the Conservatives have focused on punishment and jails — yet the Liberal Party has not had enough courage to stand up for prevention, for the need to fight the causes of crime, to reinforce the fact that crime had been going down, that the Conservatives were fear-mongering. Liberals were afraid they would “appear to be soft on crime.” We supported, indeed many times voted in favour of Conservative legislation that many thought, from both criminal and social justice perspectives, was wrong. Once again, both the NDP and the Conservatives had no trouble making their positions clear. The NDP objected strenuously — the Liberals kept saying they objected, but in the House they voted with the Conservatives. Once again, not so clear.

As the critic for international trade, I was surprised to discover that although people still said that the party supported free trade, for many Liberals, that really wasn’t true. Not only did many in the Liberal caucus not support free trade, many still objected, after all these years, to the FTA and NAFTA. When it came to foreign investment, I was surprised to discover an extraordinary level of protectionist sentiment in the Liberal caucus ranks. The Conservatives were unequivocally protrade and in favour of engaging in the world economy. And again, the NDP was clearly on the opposite side. As for Liberals, notwithstanding strong Liberal legacies in terms of economics, trade and investment — from the likes of Martin, John Manley, Roy MacLaren and Frank McKenna — our position was becoming unclear where we stood.

On taxation: Internal debates on federal funding to support implementation of the

HST in BC and Ontario were fraught with disagreement. Once the Liberal Party had recognized that implementing the GST had, in fact, been the right thing to do, over the years the party also called for harmonization, as had happened successfully in the Atlantic provinces. It was the right thing to do economically and, after all, it was up to the provinces — the vote in Parliament was only to financially support Ontario and BC should they decide to proceed. In the end, the Liberals supported it, but barely. It came down to the night before the vote — we came perilously close to voting against it and many Liberals were very public in their opposition. For a party to maintain economic credibility, this should have been a no-brainer — and we almost lost it. The Conservatives, once again, were clear. They said this was sensible economics and up to the provinces. End of discussion. If the provinces in question had trouble explaining it or selling it, that was their problem. Once again on the other side, the NDP was also clear in its objection. Regardless of one’s view of the merits, the Liberals came to their decision late, reluctantly and without conviction — not inspiring to anyone looking for confident positioning.

In foreign affairs: The Liberal Party had prided itself on having refused to participate in the invasion of Iraq, contrary to what the Conservatives advocated — yet found itself incapable of challenging a proposed purchase of 65 stealth fighter attack jets at an incredible cost — neither on the financial implications of the purchase, nor on what this meant for our foreign policy. The best the Liberal Party could do was complain that there was a lack of a competitive bid process. The public saw the Liberals not as offering something substantively different than the Conservatives, but rather only bickering over process. In addition to following the Conservatives on Afghanistan, and refusing to challenge the Conservatives’ increasingly pro-Israel stand, the reluctance to challenge the jets purchase added to why Canadians had come to see Liberals as no different from the Conservatives in terms of foreign policy. What was the Liberal Party position on foreign policy? Where was the party of Pearson’s peacekeeping, of the Land Mines Treaty, of Responsibility to Protect? Once again, it was crystal clear where the NDP and the Conservatives stood, respectively. But the Liberals?

On the environment: The Liberal Party showed courage with the Green Shift, but after the 2008 election immediately divorced itself from the concept of a carbon tax (despite many people still recognizing it as good policy); indeed, many were saying that the policy of which they had, only weeks earlier, been so supportive was now wrong. It would have done no harm to acknowledge that the “what” and the “how” had been premature, but to back away so quickly and so strongly indicated a lack of principle. And then there were the oil sands. Despite their economic importance, and notwithstanding all of the goodwill we had established in the business and economics communities across the country with our deficit slaying and tax reductions, some Liberals wanted the oil sands simply shut down. Eventually, after much uncertainty, the Liberal Party leadership expressed support for the oil sands, although qualified (rightly) by environmental concerns. But shortly thereafter, the party turned around and put forward a motion in the House of Commons advocating a ban on tanker traffic on the West Coast — a ban that would eliminate the option of an effective oil export port, largely viewed as hugely important for Canada’s oil industry. In doing so the Liberal Party immediately lost any economic credibility won (or at least not lost) through our support for the oil sands — credibility not only in Alberta, but in the many parts of the country engaged in supplying people and equipment to the oil sands. The Liberal Party was most certainly, once again, seen to be blind to the economics of the West.

What Scott Reid has written — about the much-needed changes to infrastructure, about membership drives, about fundraising and the need for change in the Liberal Party — is all true. (Although, at the grand old age of 52, I object to his suggestion that the Liberal Party must only look to people in their 40s — yes, we need change, but change comes in far more shapes, sizes, colours — and genders — than just age.) But which comes first? How can the Liberal Party raise money and gain members if people don’t know what they are joining or supporting? It simply isn’t enough to say what is needed to “regain power.” We — Canadians — must know what Liberals would do with that power. Only when it’s clear what vision the Liberal Party has for Canada, and what clear and consistent policy positions it will advocate to get us there, will Canadians want to give the Liberal Party that chance once again.

In the August issue of this magazine, Robert Asselin also talks of the future of the Liberal Party. Optimistically, he suggests that one of the reasons the recent collapse might not destroy the Liberal Party altogether is that the ideals “defended by liberals” reflect the views of a large majority of Canadians. He lists these ideals as “measured economic interventionism, redistribution of wealth, individual liberties, social justice and a balance between collective and individual rights.” The problem with such generalities is that this language could just as easily have come from the last NDP election campaign platform. Some of it could also quite easily be found in a variety of Conservative material. I agree that these general concepts reflect what most Canadians believe. The problem is that the Liberal Party has no monopoly on these generalities, and Canadian voters most certainly did not see the Liberal Party and its leaders as the one, or the only, group that would run the country accordingly. There is no question that many saw the NDP, and Jack Layton’s passionate espousal of these views, as the better representation of these ideals. But many did not see Harper and the Conservatives, by their actions, as being inconsistent with them either.

Asselin says that one of the Liberal Party’s strengths is that it has never been a party of ideology, that it has been, but must remain “in the centre” to return to being the grand party of the “centre” that Canadians identified with in the past. But maybe it’s exactly this vague language of the “centre,” without a consistent positioning, that so many Canadians now have trouble with. He does say that the party must come up with concrete solutions to modern problems — but doesn’t elaborate on what those are. My view is that the language of the “centre” is seen as the opposite of concrete — soft and vague.

Indeed, I would argue that the whole concept of a political “right” and “left” (and therefore “centre”) no longer applies in 2011. Thirty years ago the meaning of the “left” was quite clear. Those on the left favoured more taxation, a stronger central government engaging in more government intervention, strong labour union ties, strong views about equality, social justice and human rights, and the importance of government in redistributing wealth and ensuring social justice. At the same time, the “right” was clearly identified as including economic conservatism, lower taxes, smaller government, as well as conservative social values — on the role of women, marriage, the family and church.

But times have changed. Many people now hold views that are a variety of those, sometimes in quite extreme combinations. I often hear someone describing himself or herself as having, on economic issues, views significantly more market-oriented than those of the NDP and closer to those traditionally viewed as Conservative — for example, support for free trade, for lower corporate taxes, less support for unions. Yet that same person may go on to say he or she supports same-sex marriage, that we should not have gone to Afghanistan, that government should help with affordable housing and that marijuana should be fully legalized. A mix indeed. But with the arrival and increasing incidence of these varied combinations, out goes the ability to peg “left” and “right.” And without a “right” and a “left,” it’s hard to define a “centre.”

The Liberal Party had prided itself on having refused to participate in the invasion of Iraq, contrary to what the Conservatives advocated — yet found itself incapable of challenging a proposed purchase of 65 stealth fighter attack jets at an incredible cost — neither on the financial implications of the purchase, nor on what this meant for our foreign policy.

Is the person described above a “centrist”? Is he or she in the middle, really, of anything? No. He or she may not fit an outdated description of “left” or “right” but is certainly not in any “middle” of any policy. “Middle” implies a certain vague inability to come to a decision or to be able to get things done. On the contrary — our sample person holds strong views on each issue. But just because some positions are in line with the NDP and some with the Conservatives, it does not mean that person is in the middle of anything.

What is clear is that the person described above needs a political alternative to the NDP, on the one hand, and to the Conservatives on the other. He or she needs an alternative that can proudly espouse both the economic responsibility and savvy that is missing with the NDP, and the concern for social justice, human rights and equality of opportunity that is missing from the Conservatives. For the Liberal Party to be that alternative, it simply isn’t enough to just use vague terms like “progressive centrist.” It’s not enough to simply say “economically responsible.” It’s not enough to just say “balance.” Of course they sound right, and good, but none of them tells that person where the Liberal Party really stands on any issue. And shooting for the “middle” does not suggest vision — it does not inspire. As a wise person once noted, the only thing you find in the middle of the road is a yellow line and roadkill.

The Liberal Party needs to talk in real terms, in ways that people understand on specific issues. The party must say what it will do, specifically, on the economy. To differentiate it from the NDP, it must be prepared to espouse strong economic policies like free trade, the encouragement of competition, responsible taxes and smaller but efficient government. It must be prepared to seek a positive balance between business and the environment. It must not be ashamed of business and the role of the market, but rather must embrace what they can do to bring prosperity — and then reinforce how to use that prosperity for the greater good. At the same time, the Liberal Party must be able to differentiate itself from the Conservatives — to stand up for educational and community programs that increase equality of opportunity and reduce poverty. It must reinforce its position on choice. On crime, the Liberal Party must unequivocally stand against blindly relying on punishment where it has been proved not to work, and stand up for prevention and the needs of those who are mentally ill. The party must, finally, stand up for a universal publicly funded health care system, but instead of just blindly repeating the words, be prepared to work with alternative delivery systems to look at the economic efficiencies that the market can bring, working within the system, to make sure we can maintain the fundamental system that we are so proud of.

The Liberal Party must, once again, take some stands. It should reconsider the wisdom of trying to be the “big tent” that tries to please everyone but, in losing its fundamental principles, ultimately pleases few. Espouse some clear principles and people will come back in out of the rain.

In the last election, and in the few years leading up to it, platitudes about “centrist” and “social justice” and “economic responsibility” just didn’t resonate when faced with the much more clearly enunciated, and forcefully marketed, positions of Stephen Harper and Jack Layton. The Liberal Party must come to grips with what the Liberal Party really stands for, moving beyond vague, tired labels. It must then have the courage to be clear about what it stands for and what it will do, and — most importantly — it must act accordingly. This the Liberal Party has not done, and it has paid the price. But there is hope.

Photo: Shutterstock