With the publication of photos and video showing Justin Trudeau in blackface, his personal racism was there for the world to see – something that rightly causes many Canadians a great deal of discomfort. It might be more palatable to point to racist laws and policies as the core of the problem, but the Liberal leader’s past actions remind us of an uneasy truth: racism is perpetuated by individual human beings working within and upholding systems – people making decisions to act in a racist manner. This is hard to discuss and confront as a society, but we must. Every segment in society has had a hand in killing Indigenous peoples – from colonial governments offering scalping bounties to settlers for native scalps, to those who operated residential schools.

While governments create the conditions of life that lead to the premature deaths of Indigenous peoples, there are many in society killing Indigenous peoples today and they include police officers, corrections officers, doctors and average Canadians.

Some of the most comprehensive public inquiries and commissions in Canadian history, such as the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission on the residential school system and the most recent, the 2019 National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls, have pointed to a deep-seated racism and hatred towards Indigenous peoples in Canada. This racism is both systemic (found in Canada’s laws and policies) but also personal (violence and discrimination carried out by individuals).

For example, the Indian Act is federal legislation, enacted by a majority of MPs back in 1876. It has discriminated against First Nation women on the basis of race and sex ever since. Those parliamentarians chose to support legislation based on their own racist and sexist views about First Nation women. These unchecked racist and sexist views by individuals in government are drawn from the larger society, but also copied and mirrored back to society. That is why First Nation women and girls are the number one target of human traffickers. It is why there are thousands of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls and why police agencies have acted, if at all, with disdain and neglect in investigating these cases.

It is the acts and omissions of government officials, governments agencies and individuals in society that have continued to commit grave acts of violence against Indigenous peoples.

Despite the many human rights laws and protections on the books in Canada, it is the acts and omissions of government officials, governments agencies and individuals in society that have continued to commit grave acts of violence against Indigenous peoples – because of their deep-seated racist views. The Indian Act authorized the federal government to create residential schools for First Nations children. However, it was the individual teachers, priests, nuns and others in positions of power in those schools whose deeply racist and sexist views formed the justifications for the horrific acts of sexualized violence and torture committed in those schools.

Racism in the justice system is the root cause of wrongful prosecutions and the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in prison today. In 1989, the Report of the Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall Jr., Prosecution on the wrongful arrest, prosecution and imprisonment of a Mi’kmaw man, found that the justice system failed him at every turn due to the fact that he was native. Only a decade later, the Report of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba considered the abduction, sexual assault and murder of Cree woman Helen Betty Osborne and the police shooting and killing of unarmed Indigenous man J.J. Harper. The report found once again that the justice system had failed Indigenous peoples on a “massive scale,” citing racism and sexism as the root cause of violence. But, ultimately, it is the racist and sexist beliefs of individual police, judges and corrections officials that allow this broken system to flourish.

Individual racism is overt and carried out by police because they believe they can do it. It is also why, in addition to sexual assaults, Indigenous peoples suffer the highest rates of police-involved deaths in the country. Racism results in Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women and girls, as being considered expendable, exploitable and less worthy. Ontario’s Ipperwash Inquiry in 2007 on the shooting death of unarmed Dudley George found the Ontario Provincial Police were infected with “widespread racism” against Indigenous peoples, countering the myth of a few bad apples.

The suffering and death associated with racism against Indigenous peoples is so normalized, it hasn’t generated the same type of outrage as Trudeau in blackface. How will we confront the ongoing genocide against Indigenous peoples generally and against Indigenous women and girls specifically? What’s required is a review of laws, policies and economic systems, but more importantly a weeding out of racist cops, politicians, judges, doctors, teachers and social workers.

This isn’t about a Liberal, Conservative, NDP, Green or another political persuasion – all levels of government and their political parties have contributed to and maintain genocide against Indigenous peoples. All parties have failed to treat the MMIWG national inquiry’s finding of genocide as a national public safety crisis and none of them has made it the priority in their platforms. This is an epic failure on their parts, and it’s how racism is allowed to continue unabated. The only hope we have of ending racism is to make it as visible as Trudeau’s blackface and take the radical steps needed to undo the entire system that allows individuals to get away with it.

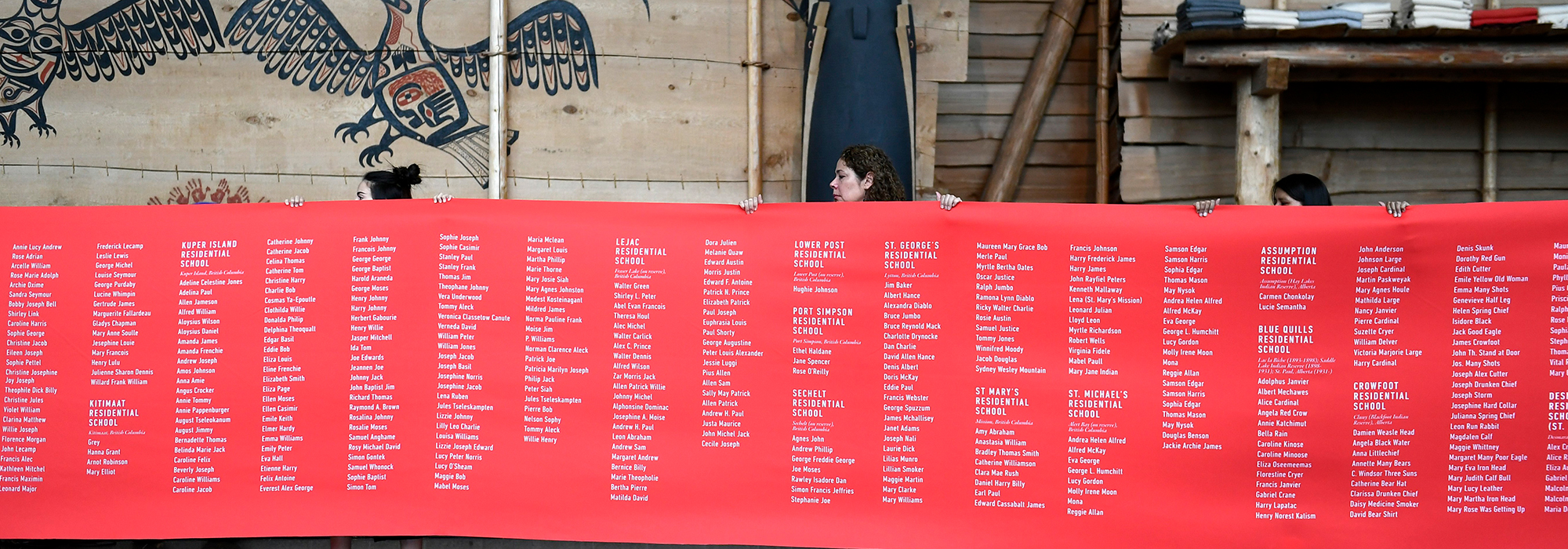

Photo: A ceremonial cloth with the names of 2,800 children who died in residential schools and were identified in the National Student Memorial Register, is carried to the stage during the Honouring National Day for Truth and Reconciliation ceremony in Gatineau, Quebec on Sept. 30, 2019. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.