The interplay of social and technological dynamics that defines the information age is accelerating the pace of change and overwhelming methods of governance. These methods were designed for a world of slower change, more limited information flow, fewer stakeholders and clearer boundaries. To succeed in a more complex, interconnected and rapidly changing world, people in all sectors are recognizing the urgent need for approaches to leadership and governance that are more inclusive, more dialogue-based, forward-looking and action-oriented. A society or organization’s ability to prosper in this world of rapid change will depend, in no small measure, on its ability to develop these new leadership and governance capacities.

In our book Catalytic Governance: Leading Change in the Information Age (University of Toronto Press, 2016), we describe one such approach. Catalytic governance is a process for leading transformative change that engages a wide range of stakeholders in dialogue and empowers them to envision and enact a desired future.

Catalytic governance

Governance, derived from the Greek kybernan (to steer) and kybernetes (pilot or helmsman), is the process whereby an organization or society steers itself. While government is central to the process of governance in society, in the information age government is increasingly only one helmsman among many, as more and more players — voluntary organizations, interest groups, the private sector, the media and more — become involved in that process. To steer effectively when so many hands (with so many different agendas) are on the wheel, a more catalytic approach to governance is needed.

The catalytic governance model recognizes that for many issues a wider range of stakeholders need to be involved (and are involved) in the governance process in the information age, and that governments, boards and other governing bodies need to make room for those players. For such issues governments and boards must relax day-to-day control (or the illusion of such control) and shift to a catalytic role, focusing on these tasks:

- framing the issues and the agenda, and setting the boundaries for a solution;

- ensuring a full range of stakeholders are engaged;

- defining the rules of that engagement;

- encouraging stakeholders to explore different perspectives in search of common ground; and

- acting on the emerging strategic direction, with legislation if necessary.

In a prescient article written three decades ago, the diplomat and educator Harlan Cleveland eloquently described why a catalytic approach to leadership and governance is essential in the information age:

In an information-rich polity, the very definition of control changes. Very large numbers of people empowered by knowledge assert the right or feel the obligation to “make policy.” Decision-making proceeds not by “recommendations up, orders down,” but by development of a shared sense of direction among those who must form the parade if there is going to be a parade…Real-life “planning” is the dynamic improvisation by the many on a general sense of direction — announced by the few, but only after genuine consultation with those who will have to improvise on it. Participation and public feedback become conditions precedent to decisions that stick.

In this process the core roles of governments and boards remain as important as ever — in particular, the responsibility to define and protect the broader public interest, including that of the voiceless (in the case of governments), or to ensure actions are taken in the best interests of the corporation (in the case of boards). What does change is not these fundamental responsibilities of governments or boards, but how they can accomplish them effectively in the information age, in particular when transformative change is required.

Another reason we need new governance processes is that the information age increasingly presents us with “wicked problems.” A wicked problem has innumerable causes, is tough to describe and does not have one right answer. It cannot be addressed with a purely scientific or rational approach because it lacks a clear problem definition. And it is difficult to tackle because effective and legitimate action requires the support of multiple stakeholders with widely differing perspectives and priorities. There are many examples, including climate change, health care, Indigenous issues, inequality and many business strategy issues.

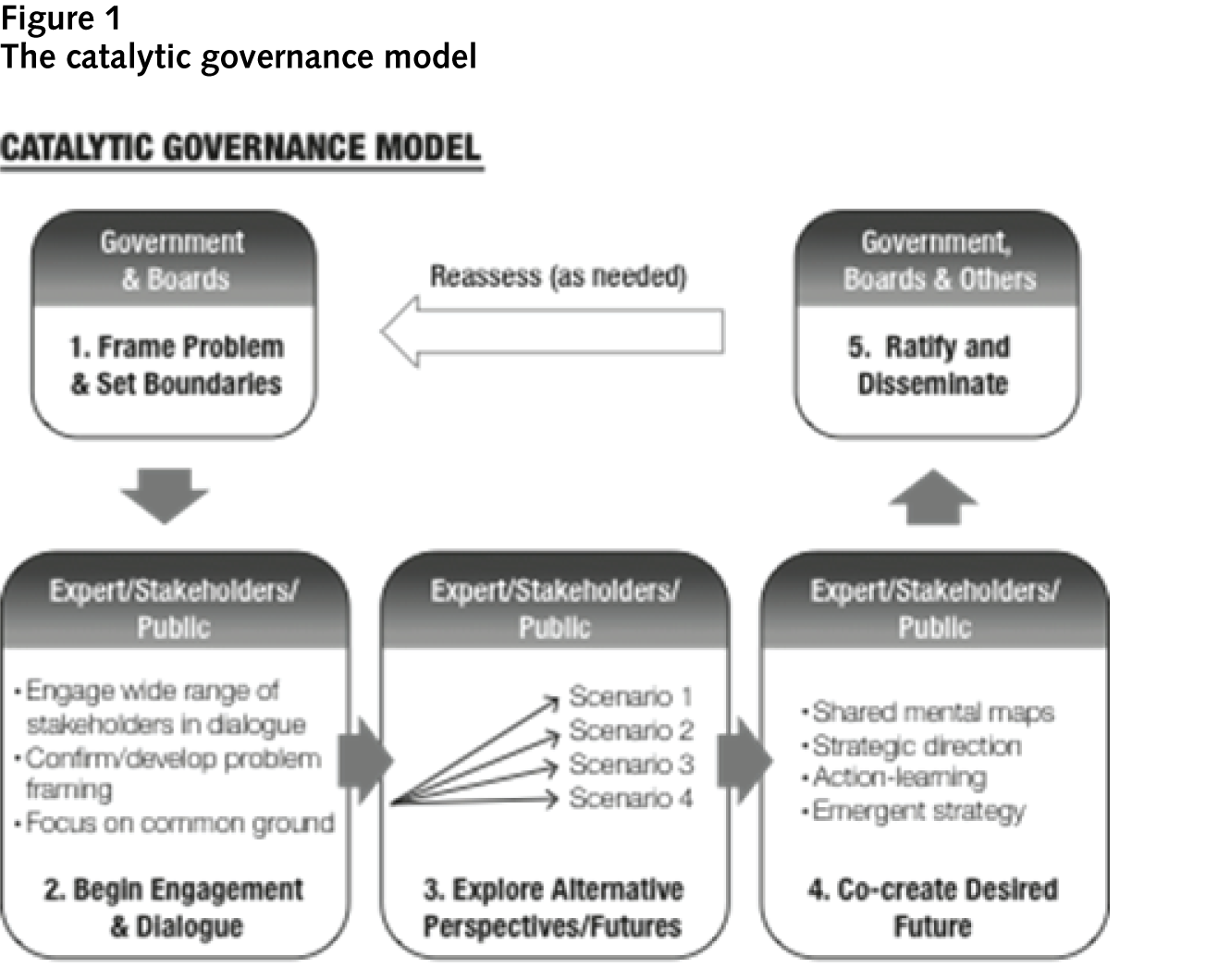

The catalytic governance model represents the type of inclusive and continuing process needed to address such intractable challenges. The model has five steps, summarized in figure 1.

- Step 1: Frame the problem and set boundaries for solutions

Governments, boards or other governing bodies (as stewards) determine whether addressing an issue requires a catalytic approach. They then frame the problem and agenda, define the process to be followed and the range of stakeholders to be included and set the boundaries for acceptable solutions.

- Step 2: Begin engagement and dialogue

Governing bodies engage a wide range of stakeholders around the issue, embedding the ground rules of dialogue and engagement in all conversations from the outset. Governing bodies need to ensure that all the key stakeholders and viewpoints are included in the process, including those normally underrepresented. The stakeholders should be selected to be a microcosm of the system at issue, not just representatives of particular interests. In a true dialogue, participants need to be free to speak for themselves, not as representatives. A continuing and expanding process of dialogue and engagement is fundamental to catalytic governance.

- Step 3: Explore alternative perspectives and futures

The third step in the process is to explore in detail a variety of perspectives on the issue and alternative possibilities for how it may unfold in the future. This provides a way for participants to understand and learn from others’ points of view, and to start to see the limitations of their own. Ensuring that multiple viewpoints are taken into account creates a richer view of the issue and its possibilities. Focusing on alternative futures also takes the spotlight away from current controversies and creates more opportunities to find common ground: many people find it easier to discover areas of agreement when talking about what they want to see in the future.

- Step 4: Co-create the desired future

The fourth step is for stakeholders to define their desired future and to develop practical action steps to realize that future. Often this will require a process of action learning — taking experimental actions and learning from the result. To be effective, the stakeholder group must include key individuals who are in a position to bring about change and willing to take action.

- Step 5: Ratify and disseminate the desired future

In the final step, governments, boards and other governing bodies play a leading role, first by ratifying and disseminating the result of the catalytic governance process, and then by acting and encouraging action on the emerging strategy (including legislating if necessary) and monitoring the results. This step is not a simple, once-and-for-all end point; it is itself a process of action learning.

A test case: Transforming Canada’s payment system

The recent transformation of Canada’s payment system provided an opportunity to test and further develop catalytic governance.

Payments are everywhere. From coffee purchased at a coin-operated machine to the daily exchange of billions of dollars among corporations, financial institutions and governments, the transfer of value underpins our economy. Every year, Canadians make over 25 billion payments, worth more than $45 trillion. These payments allow people to run households, make it possible for businesses and other organizations to operate and let governments fund essential programs. But the payments business is undergoing a dramatic shift. Just as the industrial revolution brought massive change in production and manufacturing, the information revolution is changing our payments system.

The reform effort that began in 2010 was sparked by years of stakeholder complaints about the Canadian payments system. Small and medium-sized businesses were upset about the escalating merchant discount fees on credit cards; individuals were perplexed by the myriad rules, regulations and service charges for small payments; large corporations complained that existing systems could not carry enough information for them to automate the processing of their receivables and payables. New entrants were concerned about access to payments system infrastructure and the uncertainty created by a patchwork of regulations. And Canada did not have a plan to move from paper-based payments (cash and cheques) to digital immediate funds transfer.

In June 2010, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty announced the creation of the Task Force for the Payments System Review. Flaherty mandated the task force to “conduct a review, given the importance of a safe and efficient payments system, to ensure that the framework supporting the Canadian payments system remains effective in light of new participants and innovation.”

Given the complexity, rapid change and resulting uncertainties of the payments environment, the task force recognized that a traditional approach (conducting research, hearing stakeholder and expert opinions and then making recommendations) would not be adequate. Instead it chose to take a catalytic approach and make dialogue its guiding principle: it called on consumers, industry, government and businesses to work together to build the payments system we need. To focus that dialogue and to explore alternative plausible futures for the Canadian payments system, the task force helped to convene and participated in a payments round table, which brought together leaders from the banks and other financial institutions, technology and telecom companies, retailers, consumers and more.

At the outset of the review, there was open suspicion and hostility among the disparate voices. But over time, as the dialogue continued and deepened, participants began to find unexpected areas of common ground, learning to trust the process and widen the circle of engagement. People began to see things they hadn’t seen before or hadn’t fully appreciated and began to work together to devise better approaches to what they increasingly saw as shared challenges.

When a “coalition of the willing” emerged from the round table ready and able to develop initiatives to co-create a preferred future, the task force provided resources to support working groups and advisory groups of stakeholders to begin to realize that future. These groups began the practical work of drafting and testing initiatives to transition Canada from paper-based to digital payments, including building a digital identification and authentication regime, implementing electronic invoicing and payments for business and government, creating a public-private mobile ecosystem and upgrading Canada’s clearing and settlement infrastructure.

What transpired over 18 months was transformative, as mindsets shifted and mental maps were redrawn, and as trust and a sense of community grew. What began as 40 leaders, with different and sometimes conflicting agendas and perspectives, became the core of an energized and more inclusive “payments industry,” working together to make the governance and other changes needed to take the Canadian payments system into the digital age.

In the end, the task force delivered a widely supported action plan that enabled government and industry to act on all four of its recommendations within two years. The built-in support provided by the catalytic process allowed the government to pass legislation that moved control of the payments system from the banks to an independent board, which then replaced the system’s dramatically outdated infrastructure. This was accomplished without the government expending much if any political capital.

Governing by creating shared meanings and frameworks

Effective governance in the information age depends more on creating shared meanings and frameworks and less on traditional, top-down approaches. Such governance is more inclusive, learning-based and action-oriented. It is designed to address the wicked problems we face in the information age. It produces both a road map and a community of practice prepared to take action.

In our new era, leaders who fail to engage a wide range of stakeholders in meaningful dialogue risk developing solutions that fail to get traction and potentially drive mistrust, disengagement and resentment.

Not every decision by a government or a board requires use of the catalytic model. There is still an important place for traditional methods to deal with smaller or more straightforward decisions. But when the issue has innumerable causes, is tough to describe and does not have one right answer, and when it is difficult to tackle because effective and legitimate action requires the support of multiple stakeholders with widely differing perspectives and priorities, that’s when a catalytic process is beneficial. These are the big challenges of our day.

Catalytic governance turns the chaos of voices into an advantage. It creates a pathway for genuine dialogue and stakeholder influence. It encourages the development of shared solutions. It is effective governance for the information age.

Photo: Shutterstock/by Monkey Business Images

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.