How did the Canadian economy perform during the Harper government years, what factors drove this performance, and what role did Harper government policies play in achieving broad economic objectives? In this chapter, we first compare the performance of the economy during the years of the Harper government (2006-15) with that of the preceding 22 years.and then identify which factors drove this performance, so that we can assess the importance of federal interventions. Then we examine these policies and their effects in the light of objectives that any central government should pursue: stabilization, long-term growth, income distribution and sound public finances.

How did the Canadian economy perform during the Harper government years, what factors drove this performance, and what role did Harper government policies play in achieving broad economic objectives? In this chapter, we first compare the performance of the economy during the years of the Harper government (2006-15) with that of the preceding 22 years.and then identify which factors drove this performance, so that we can assess the importance of federal interventions. Then we examine these policies and their effects in the light of objectives that any central government should pursue: stabilization, long-term growth, income distribution and sound public finances.

Broadly speaking, our assessment reveals that Canada’s overall economic performance during the Harper years was largely driven by external forces, while domestic policy initiatives played a relatively minor role, except during 2008-10. We would argue that the Harper government’s economic policies met the objective of strengthening Canada’s fiscal position without jeopardizing the goal of income redistribution. After 2010, however, in the face of a persistently slow recovery of demand, the Harper government unduly sacrificed economic growth, in particular public investment, in order to improve a debt position that was already solid.

Canadian economic performance during the Harper years

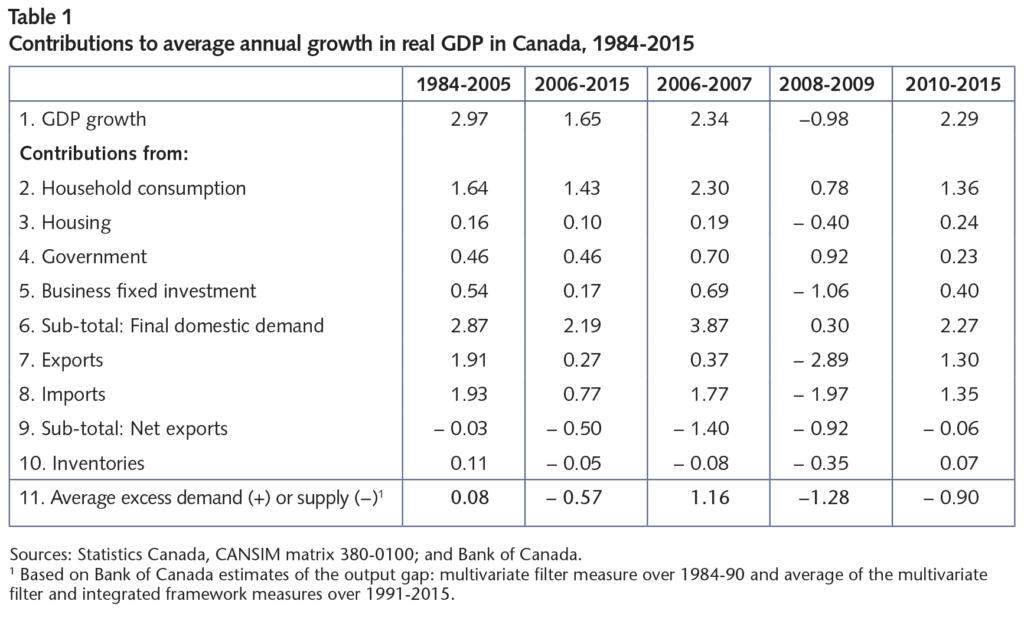

During the period of the Harper government (2006-15), real GDP growth was markedly slower than during the preceding 22 years (table 1, row 1), a result of the sharp recession that occurred from the fourth quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2009, and of the period of sluggish recovery that followed.

The main source of weakness during the recession was real exports (row 7), which suggests that external demand played a preponderant role. The moderate pace of the recovery over 2010-15, on the other hand, stemmed from (a) tepid growth in real consumption (row 2), partly due to a rise in the household saving rate relative to 2002-08; (b) continued decline in real net exports (row 9), due to a comparatively muted rebound in foreign activity and a loss of cost competitiveness; and (c) a sharp slowdown in government spending (both consumption and investment) (row 4). On average, the Canadian economy experienced significant slack during the Harper years in contrast with the rough balance between aggregate demand and potential output from 1984 to 2005 (row 11). (During 1984-2005, there were years of large excess supply, as in 1991-93 and 1996-97, and years of large excess demand, as in 1988-90 and 1999-2000. We interpret the small average excess demand over the whole period, 0.08, as indicating a rough balance overall, especially since estimates of the output gap have a large confidence interval about them.)

The fluctuations in aggregate demand growth in Canada during the Harper government years gave rise to considerable adjustments in the labour market. Not only did employment growth slow relative to labour force growth when compared to 1984-2005, but also average hours worked per worker fell far more rapidly and the labour force participation rate retreated from its prerecession high (table 2). Even during the recovery, labour force participation continued to decline, at least in part because the older members of the baby boom generation were beginning to retire.

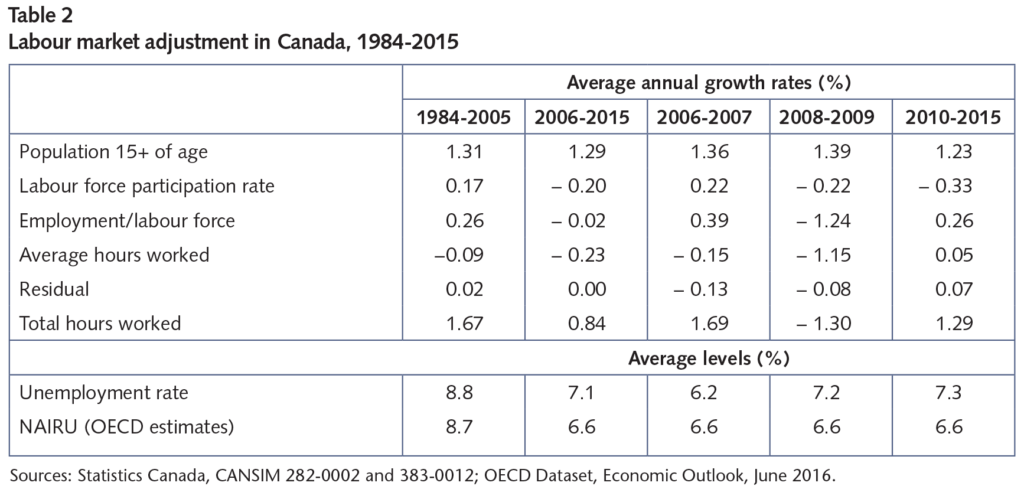

Remarkably enough in view of the greater slack in the economy during the Harper government years, the unemployment rate was considerably lower than during the previous two decades. This reduction reflects a marked decline in the structural component of the unemployment rate, a decline that preceded the arrival of the Harper government. The OECD estimated the NAIRU in Canada to have fallen from a peak in 1993 and stabilized at around 6.5 percent by 2006 (figure 1). (NAIRU stands for non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment. It is the lowest unemployment rate that can be achieved without risking an acceleration of inflation.) Thus the policies and structural developments which were at the root of the lower level of structural unemployment in the last decade unfolded well before the Harper government years.

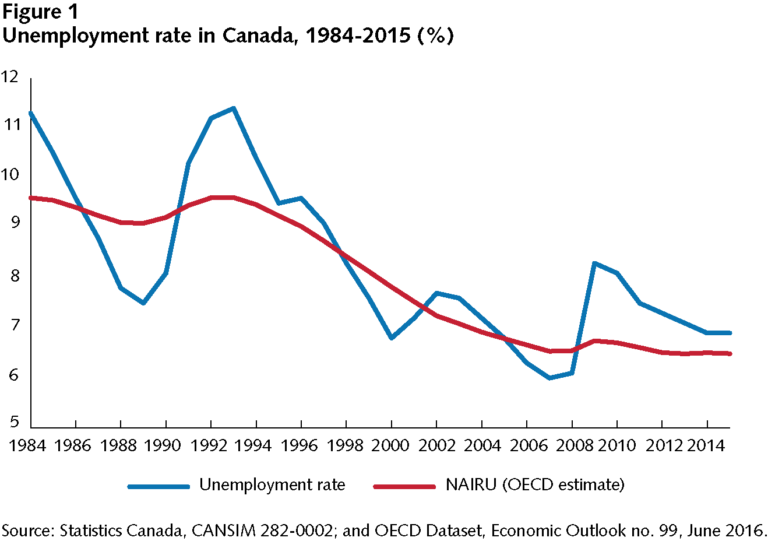

While the Canadian economy during the Harper government years worsened on most aggregate measures relative to 1984-2005, it did quite well relative to foreign advanced economies. While many of these economies faced severe internal problems such as broken financial systems and a collapse of their housing markets, the Canadian economy essentially had to cope only with weak external demand. As a result, not only was the 2008-09 recession less severe in Canada than in most other advanced economies, but also the recovery in Canada was stronger (table 3). Moreover, employment growth in Canada over 2006-15 was far stronger than in the US and the other advanced economies.

Labour productivity growth, on the other hand, was significantly slower in Canada than in the US, which suggests that the comparatively strong gains in Canadian employment may have been achieved partly at the cost of slower productivity growth. Canada had a lower unemployment rate over 2006-15 than over 1984-2005, an experience shared by Germany, the United Kingdom and Italy but not by the United States and most other advanced economies.

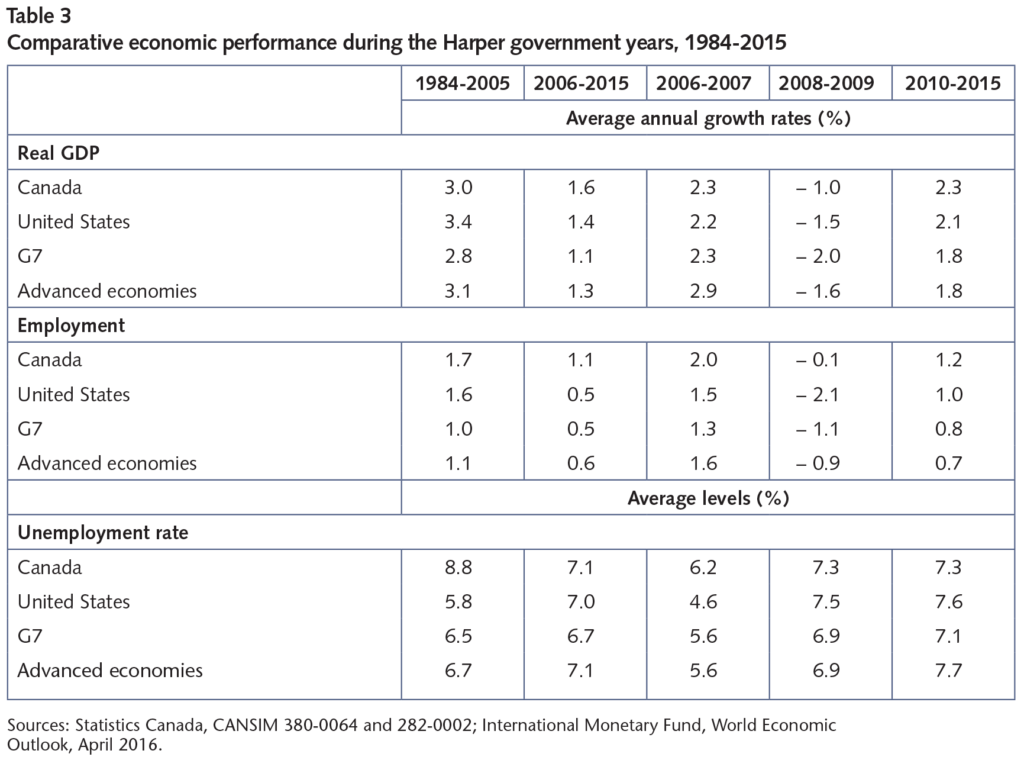

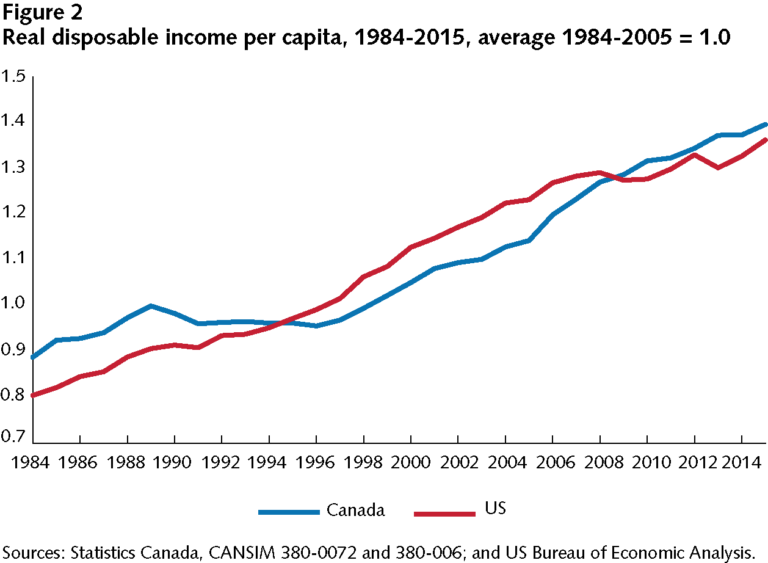

Finally, in contrast with 1984-2005, the Harper government years witnessed significant progress in real disposable income (after-tax personal income less inflation) per capita in Canada relative to the US (figure 2). In fact, not only was the growth rate of real disposable income per capita in Canada double the rate in the US over 2006-15, it was also much faster than over the Mulroney-Chrétien-Martin years as a whole in Canada.

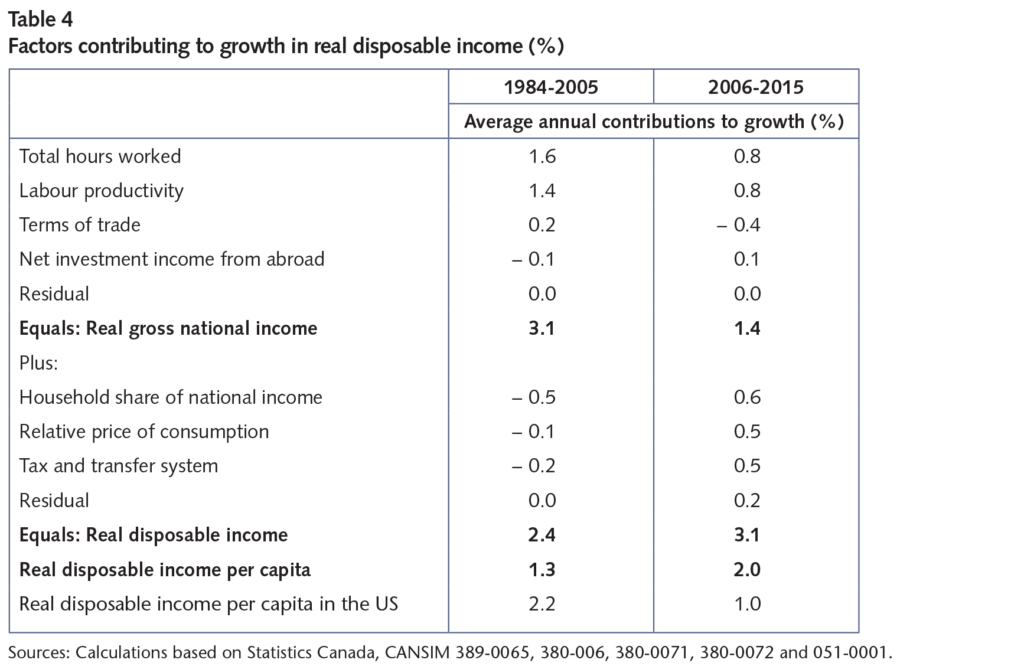

The strengthening of real disposable income growth in Canada during the Harper government years relative to 1984-2005 occurred despite weaker contributions from hours worked, labour productivity and terms of trade (table 4). (For an analysis and projections of the sources of household real disposable income growth in Canada and details on the underlying analytical framework see this analytical report we wrote with Michael Horgan.)

That real disposable income growth increased during the Harper years was due to several factors: the household share of net national income rose instead of declining as during 1984-2005; the price of consumption increased less rapidly than the price of final domestic demand rather than rising more rapidly as during 1984-2005; and the tax and transfer system withdrew funds from households at a lesser rate than during 1984-2005. In addition, net investment income from abroad made a positive rather than a negative contribution to real income growth during the Harper years.

Drivers of Canadian economic performance during the Harper years

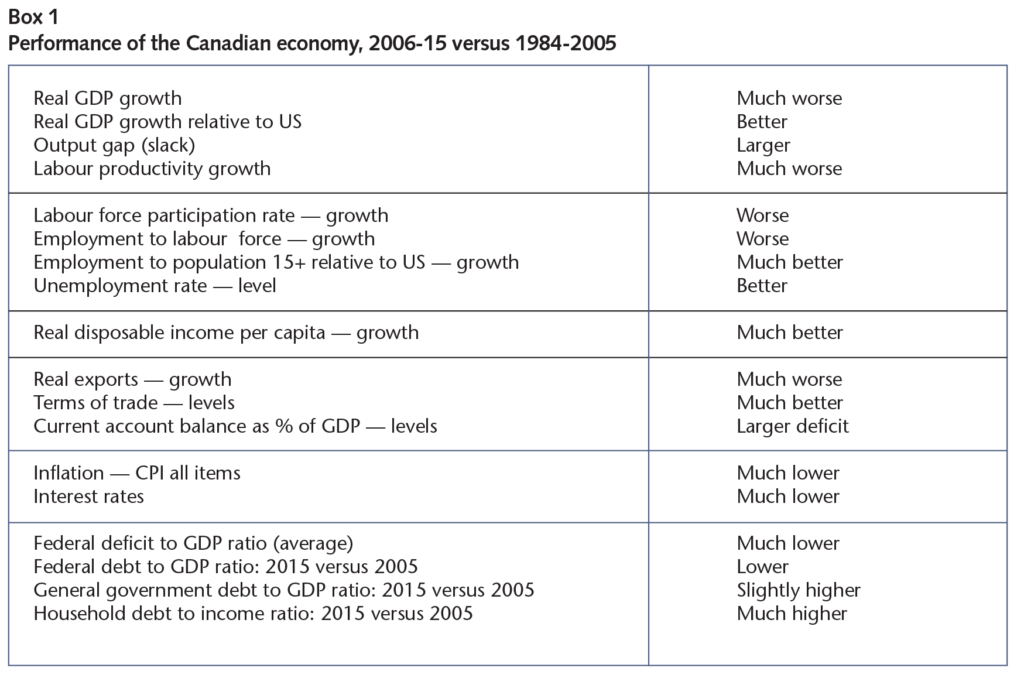

Canadian macroeconomic performance during the Harper government years was driven largely by global economic developments, while federal economic policy had a relatively minor effect on Canadian performance, except during 2008-10. Box 1 summarizes the comparative behaviour of key macroeconomic indicators for Canada during the Harper government years.

To understand some of the external forces and built-in domestic political, social and economic structures that shaped Canada’s economic performance during the Harper years, we’ll take a look at seven key drivers — of which only one, discretionary fiscal policy, was within the control of Canadian governments.

Global economic growth

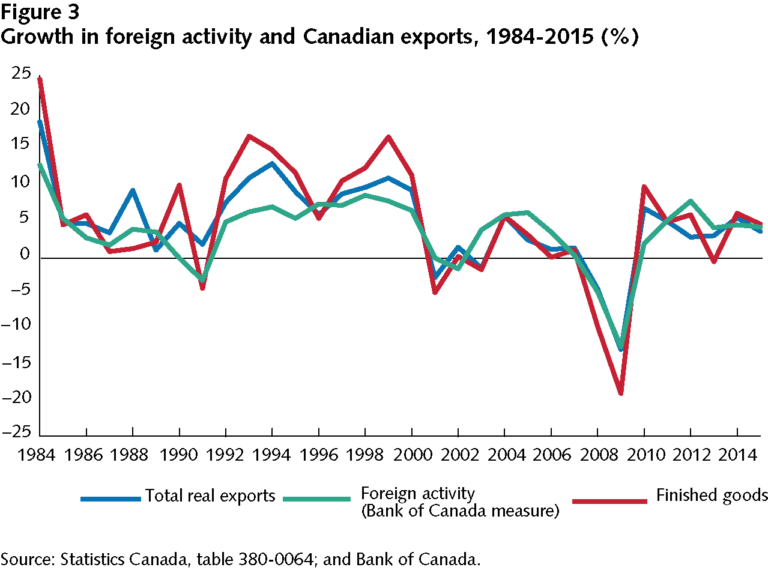

The first force acting on Canadian real GDP growth was external activity growth, which drives demand for Canadian exports. (The foreign activity measure is compiled by the Bank of Canada.) Foreign activity growth collapsed during the Harper government years, compared to the previous two decades, due to the severe recession in the United States in 2008-09 (figure 3). The direct impact on Canadian exports was a key source of the weaker Canadian real GDP growth during 2006-15.

Industry-specific trends or shocks were also involved: an uptrend in real exports of crude oil and bitumen, a continued downtrend in real exports of forestry products, a significant restructuring of the North American automotive industry in 2008 and 2009, and continued weakness in real exports of electronic products following the sharp drops that resulted from the burst of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s.

Commodity prices

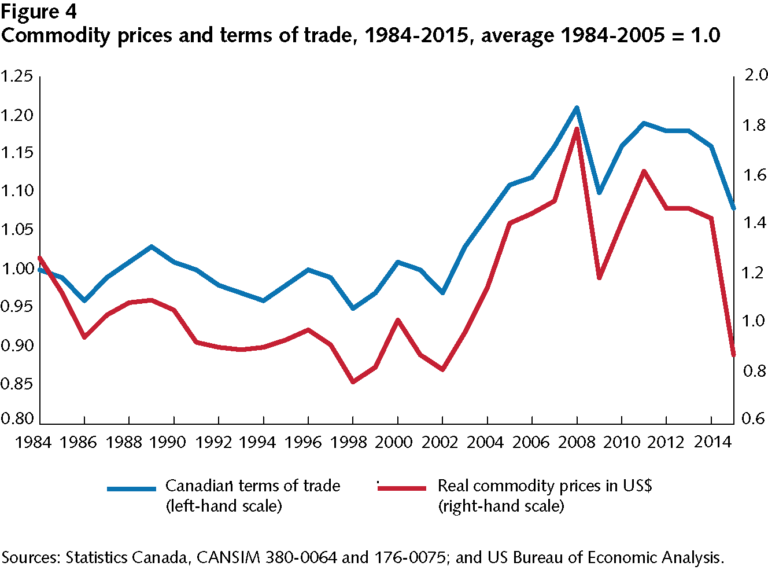

Real commodity prices rose strongly from 2003 to 2008 and remained at relatively high levels until 2014 (figure 4). Canada’s real income as a country got a boost from high global commodity prices because more goods and services could be purchased out of the revenues from Canadian sales of commodities, notably oil. The implied gain in terms of trade and real market income in Canada supported stronger growth in domestic spending and production. Resource industries had a greater incentive to invest than other sectors and, indeed, substantially contributed to growth in business fixed investment during 2006-13. The sharp drop in commodity prices in 2015 set in motion a reverse process of falling growth in real income and spending in Canada, and a collapse of investment in the oil and gas sector.

Cost competitiveness

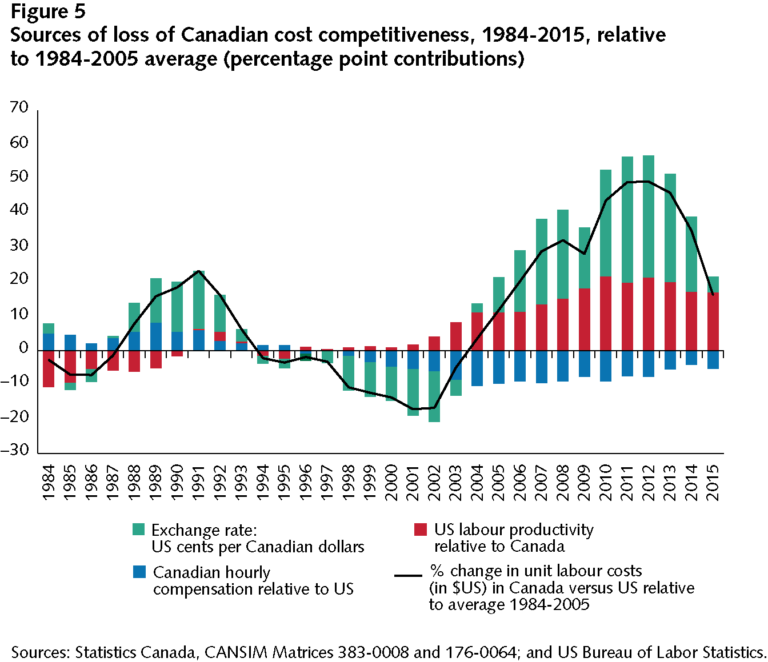

A substantial loss of Canadian cost competitiveness depressed Canadian real net exports and hence real GDP in the Harper government years relative to 1984-2005. Along with the increased presence of China as a competitor in the US market, it contributed to a fall in Canada’s market share of US manufacturing imports. That loss of competitiveness contributed to a significant widening of Canada’s current account deficit relative to GDP during the Harper government years, more than offsetting the effect of a rise in the terms of trade during the period.

Measured in terms of unit labour costs (in US dollars) in Canada versus costs in the US (relative to the 1984-2005 average), a loss of Canadian cost competitiveness in the business sector emerged in 2004 (3.7 percent). This loss (represented by the black line in figure 5) grew to a peak of 49 percent in 2011 before retreating to 16 percent in 2015. A substantial appreciation of the Canadian dollar accounted for 70 percent of the total loss of competitiveness during 2006-15 relative to 1984-2005. This appreciation was largely driven by a sharp increase in commodity prices, notably oil prices. A slower rate of labour productivity growth in the business sector relative to the US, which on its own would have accounted for 50 percent of the competitiveness loss, was nearly half offset by slower wage growth in Canada (figure 5).

Interest rates and Canadian monetary policy

Lower interest rates during the Harper years, shaped by monetary policy from the Bank of Canada, contributed to growth by lowering the cost of servicing debts for households, businesses and governments and boosting domestic asset prices and net worth. The target overnight rate reached a peak of 4.5 percent in July 2007 and started a steep slide in January 2008 before reaching 1 percent or less in 2009-15. It must be emphasized that the slide in interest rates since 2007 was part of a global phenomenon of monetary policy loosening. In fact, the (real) Canada-US short-term interest rate differential turned somewhat in favour of Canada in 2008 and remained so until 2015.

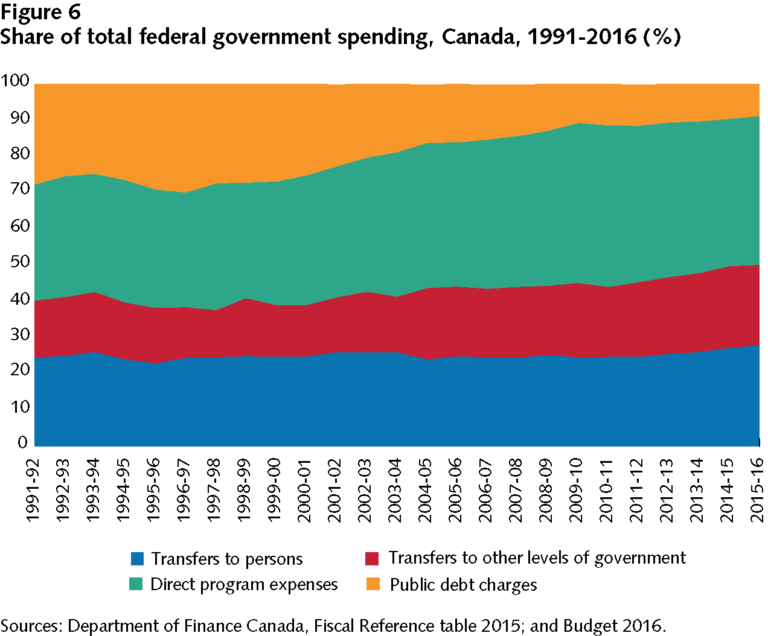

Because of the low and declining interest rates, household debt service payments continued to trend downward relative to disposable income even as the debt-to-income ratio rose substantially. At the same time, lower interest costs relative to government revenues gave more room to the Harper government (and to provincial governments) for spending on direct programs and transfers and for reducing taxes without increasing the federal (or provincial) deficit (figure 6).

Canadian financial sector

The stability of the Canadian banking system meant that private spending was not restricted by credit constraints in any significant and persistent manner, as was the case in other countries. Nor did the federal government have to spend billions of dollars to bail out failing financial institutions, as was the case elsewhere.

The financial stability Canada enjoyed in that period was built on measures put in place before the Harper government came to power. Since the late 1980s, the supervisory regime in the financial sector had evolved and improved to include clearer goals, improved incentives and more accountability as well as increased flexibility for relevant financial authorities to intervene earlier with troubled institutions. At the outset of the global financial crisis, Canadian banks held fewer toxic assets and had strong capital ratios, higher levels of liquid assets as a share of total assets and a high ratio of depository funding compared with their international competitors.

Housing market

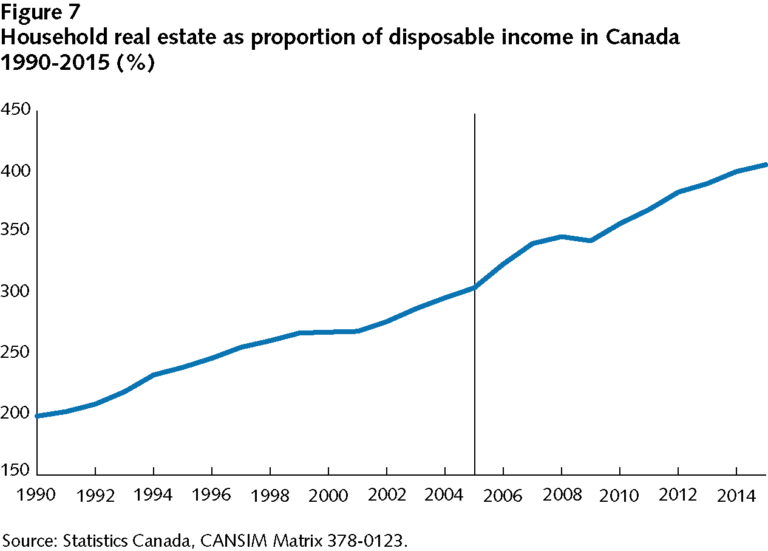

The relative buoyancy of the Canadian housing market also helped to buttress the Canadian economy during the Harper years. This buoyancy was reflected in low rates of mortgage delinquencies and defaults and in a significant rise in the value of household real estate to disposable income (figure 7). This strong performance stemmed from several factors: the housing price cycle was relatively subdued, and real house prices in particular rose much less in Canada than in the US over 1997-2005 without collapsing in subsequent years as in the US; the quality of verification and documentation demanded by lenders was high; and mortgage lending standards were relatively high until the mid-2000s. Mortgage insurance standards were inappropriately allowed to get looser in 2006 but too late for a significant subprime market to develop. The Harper government reversed course and tightened these standards between 2008 and 2012 as the global financial crisis unfolded.

The buoyancy also meant that the contribution of housing expenditures to real GDP growth wasn’t nearly as negative in Canada as in the US from 2006 to 2009, and was more positive from 2010 to 2012. It also meant that Canadian households felt far less need after the crisis to put money away and reduce their family debt levels than those in the US. Along with firmer growth of real disposable income in Canada, this led to a stronger contribution of household consumption to real GDP growth in Canada than in the US during the Harper government years.

Government fiscal policies

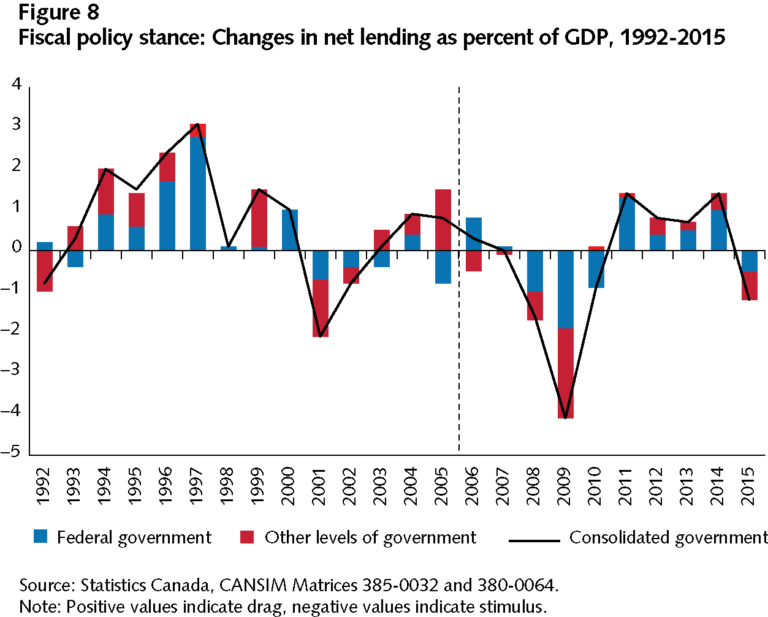

A final force at play was the fiscal policies of governments in Canada. Fiscal policy stance is measured by changes in actual net lending of governments as a percentage of GDP. This measure incorporates the effect of automatic stabilizers (such as employment insurance, income taxes) and therefore captures more than purely discretionary fiscal policy. Moreover, it includes net acquisition of nonfinancial capital (investment in infrastructure), a key element of the fiscal stimulus implemented in response to the economic downturn.

So defined, fiscal policy by all levels of government was slightly restrictive in 2006, neutral in 2007 and expansionary in 2008-10, with the federal government accounting for nearly 60 percent of the total stimulus during those three years (figure 8).

Fiscal policy turned moderately restrictive in 2011-14, with the federal government accounting for about three-quarters of the resulting fiscal drag, before becoming mildly expansionary in 2015 due to the effects of automatic stabilizers in the context of a much weaker economy. Beyond the effects of automatic stabilizers, the discretionary fiscal policies of federal and provincial governments helped to substantially mitigate the recession in 2008-2010 but actually slowed the recovery afterwards.

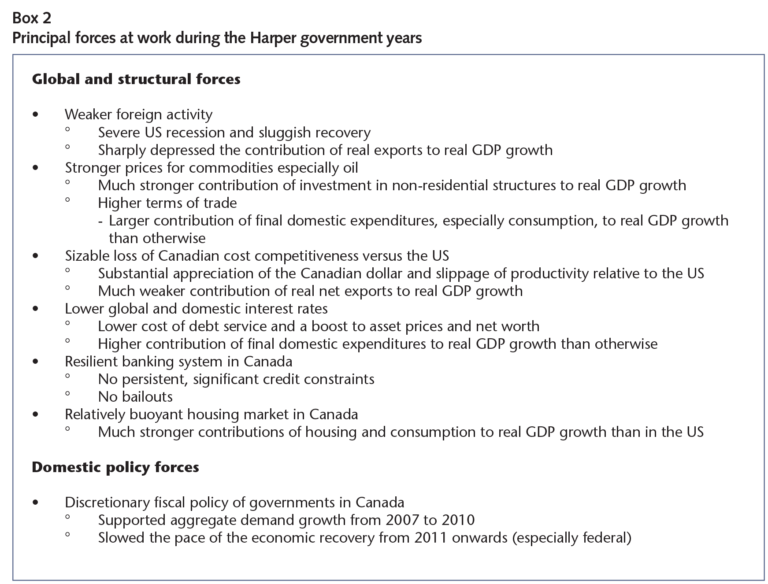

Box 2 summarizes the key forces at play in the performance of the Canadian economy during the Harper government years.

Economic policies of the Harper government

In this section we concentrate on the Harper government’s record on fundamental economic objectives: stabilization, long-term growth, income redistribution and maintenance of a sustainable ratio of public debt to GDP. In organizing our analysis on the basis of these fundamental objectives, we follow the classic framework for analyzing economic policy set out by Richard Musgrave in the 1959 book The Theory of Public Finance.

Stabilization policy

Stabilization policy can be divided into three key elements:

- monetary policy — the setting of interest rates by the central bank, which in Canada is organized around a clear inflation target

- fiscal policy — the balance of expenditures and revenues

- financial and “macroprudential” policies

Policy should try to steer the economy on a middle course between excess demand and excess supply to avoid excessive inflation or anemic economic activity.

Monetary policy

Monetary policy, based on the inflation-targeting policy executed by the Bank of Canada, played a stabilizing role in 2006-15. In 2006, a long-standing inflation-targeting agreement between the government and the Bank of Canada, which states that the central bank will aim for an inflation target of 2 percent, was renewed on essentially the same terms as those agreed previously. That agreement was renewed again in 2011. A lot of research work supported such renewals, and the Harper government made the right decision in going ahead with them.

However, because monetary policy is conducted independently by the Bank of Canada, we will confine our analysis of stabilization to fiscal and macroprudential policies that are actually conducted by the government.

Fiscal policy

A government deploys its fiscal policy to “lean against the wind” in order to contribute to keeping aggregate demand as close as possible to potential output, while ensuring that public debt remains sustainable. Simply put, the goal is to contribute to growth within a reasonable speed limit; otherwise inflation or anemic activity can result.

Stabilization requires that a government incur growing deficits in relation to GDP during periods of increasing slack in the economy, incur increasing surpluses in relation to GDP as excess demand grows and stop providing stimulus as higher private demand boosts growth enough to bring aggregate demand closer in balance with potential output. (Fiscal stimulus here refers to an increase in net borrowing — deficit plus net acquisition of nonfinancial assets — as a percentage of GDP. Although it does not measure the impact of the increase in deficit on real GDP growth directly, clearly this impact is correlated with the size of the fiscal stimulus as defined here.)

Because of the structure of ongoing tax, transfer and expenditure policies, the fiscal balance automatically changes to provide some fiscal stimulus when the economy slows and some fiscal drag when the economy grows faster. Such automatic stabilization may be inadequate during a severe downturn, and governments may lower tax rates or increase growth in program spending to boost aggregate demand. (The incentive to mitigate a downturn is all the greater if it is believed, as several economists do, that pronounced slack in the economy leads to persistent slower potential growth as a result of lower investment, degradation of skills, etc.) Conversely, during a boom, governments may raise tax rates or cut growth in program spending to cool the economy.

However, achieving the proper timing and size of discretionary fiscal policy initiatives on stabilization is a challenge, given that readings of the output gap — that is, the amount of slack in the economy — as well as economic forecasts are subject to large errors. In addition, the size of, and lags in, the effects of fiscal policy measures are variable, and flexibility is limited when adjusting fiscal policy to changing circumstances.

Probably the best that can be reasonably expected is (a) that a government provides a stimulus to growth during a downturn by expanding the deficit in relation to GDP with discretionary measures to supplement automatic stabilizers; (b) that a government refrains from introducing measures to quickly reduce this deficit in relation to GDP before excess supply is substantially eliminated, thereby giving the recovery a chance; and (c) that during periods when inflationary pressures mount (generally after several years of strong growth), a government should at the very least not exacerbate excess demand through expenditure increases or tax cuts that further fuel aggregate demand growth.

On the basis of these minimal expectations, the Harper government’s fiscal policy turned out to be appropriately restrictive, but unintentionally so, in 2006-07; it was appropriately expansionary, but fortuitously so, in 2008; it was appropriately and intentionally very expansionary in 2009-10; and finally, it was intentionally restrictive, but inappropriately so, over 2011-15 as a whole (figure 7).

The Canadian economy was in significant excess demand from the second half of 2005 through to the third quarter of 2008, although excess demand was considerably smaller in the first three quarters of 2008 than in 2007, according to one measure of the output gap. (The two measures of the output gap estimated by the Bank of Canada differ markedly on the size of excess demand during 2008. The “integrated framework” measure indicates much smaller excess demand than the “extended multivariate filter” measure.)

While the Bank of Canada was raising its policy interest rate to stem inflationary pressures from rapidly increasing excess demand in 2006 and 2007, the federal government added to inflationary pressures by cutting taxes and maintaining a strong pace of program spending during these two years. Among other tax measures, the GST was cut from 7 to 6 percent in July 2006 and from 6 to 5 percent in January 2008. Total program spending increased at an average annual rate of 6.9 percent in 2006-07 and 2007-08.

The strategy of the government was to use the strong tailwind provided to revenues by an economy in boom to grant tax relief and allow robust expenditure growth without compromising further decline in the net debt-to-GDP ratio. In the end, the federal government increased its net lending (surplus) by 0.8 percent of GDP in 2006 and 0.1 percent in 2007 (these figures include the effects of automatic stabilizers), but only because of the stronger than anticipated economy. Discretionary measures taken by the government reduced the size of the surpluses that should have been generated if the government had given priority to stabilization.

The federal government relaxed its fiscal stance by 1 percent of GDP in 2008, mostly through reductions in the GST rate from 6 to 5 percent and through cuts in personal and corporate income taxes that were announced in the 2007 economic statement. Again, these measures were not introduced with stabilization in mind. Indeed, in view of the solid growth forecast for 2008 and 2009 in the economic statement, these measures were inappropriate for stabilization because they would have exacerbated excess demand if the forecast had been realized. As it turned out, these tax cuts fortuitously helped stabilize the Canadian economy in 2008 as the US economy started a downturn early in the year, thereby exerting a drag on the Canadian economy as the recession finally set in late in the year in Canada, contrary to expectations. Thus, the federal fiscal stance in 2008 turned out to be appropriate for stabilization only because of planning errors (i.e., the forecasts for growth in the short term proved far too optimistic).

Growth forecasts were adjusted downward again between the 2007 economic statement and 2008 budget, but the projected slowdown was limited largely to 2008 as a rebound in growth to near the 2007 rate was forecast for 2009. Even after further downward adjustments to growth forecasts for 2008, 2009 and 2010, the November 2008 economic statement still predicted real GDP growth in 2009 and did not introduce any significant new measure to support aggregate demand. This was a major error in light of the severity of the downturn that had clearly begun in the US in the first quarter of 2008, although the coming crisis was starting to be evident to Canada only in the fourth quarter of 2008. Indeed, the policies set out in the November economic statement were generally seen as so inappropriate that they triggered a threat by the opposition parties to defeat the minority Harper government, a threat that was thwarted only by the prorogation of Parliament.

It was only at the end of January 2009, with the Economic Action Plan, that substantive new measures to stimulate the economy were introduced to fulfill Canada’s commitment at the Washington G20 summit in November 2008. With the Economic Action Plan (in addition to limited additional initiatives in the 2010 budget) and the effects of the automatic stabilizers, the federal government appropriately generated additional fiscal stimulus of 1.9 percent of GDP in 2009 and 0.9 percent of GDP in 2010, at a time when the economy was in large excess supply.

As GST rates had already been reduced by two points and cuts in income taxes for 2009 had been introduced, the main discretionary stimulus action had to come from the spending side. One key action was to spend more on infrastructure projects. An ongoing infrastructure program was ramped up, its core consisting of “shovel-ready” projects that had to be completed within two years or a little more to be eligible for federal support. Because the focus of the infrastructure program was “stimulus” pure and simple, the quality of many of these “shovel-ready” projects was modest for what was most needed to support long-term growth. The core program also effectively ended in 2011, too soon in light of the fact that excess supply in the economy resumed increasing in 2012 to reach significant levels in 2012-15 as economic growth fell to subpar rates on average. Other important actions taken in 2009 by the federal government to provide a stimulus to the economy included the bailout of GM Canada and Chrysler Canada in 2009 (in collaboration with the Ontario government) and the introduction of the one-year Home Renovation Tax Credit.

The federal government and private forecasters repeatedly overestimated short-term growth rates in Canada, presumably because they did not take into account the persistent negative effects of the financial crisis on growth in advanced economies and the detrimental effect of the loss of Canadian competitiveness. In any event, the federal government steadily trimmed its net borrowing (deficit) in relation to GDP over 2011-14 by the equivalent of 0.8 percent of GDP per year, thereby slowing the recovery and exacerbating excess supply. In a more typical recovery setting, when actual growth greatly exceeds potential growth, this would have had a relatively benign effect. But in the muted recovery setting that followed the recent global financial crisis, even a moderate fiscal drag was unwelcome. In spite of the government’s stated goal of putting emphasis on jobs and the economy, the Economic Action Plan over 2011-15 was in fact an economic inaction plan that subordinated the stabilization goal of growth to the goal of returning to balanced budgets through cuts in direct program spending, an inappropriate focus given the sluggishness of the economic recovery.

Contributing effectively to stabilization with discretionary fiscal policy is admittedly a difficult task. In spite of its incomprehensibly misguided November 2008 statement, the Harper government did a good stabilization job over the 2008-10 period of global financial crisis, although only fortuitously so in 2008. But because it was obsessively focused on reducing the federal deficit over fiscal years 2011-12 through 2015-16, the Harper government unnecessarily contributed to a slower, rather more muted recovery in Canada through to 2015 than a more appropriate fiscal policy would have produced.

Macroprudential policy

Macroprudential policy consists of rules for financial institutions, markets and instruments (such as mortgages). Its aim is to reduce the risk and the macroeconomic costs of financial instability.

One key macroprudential measure pursued by the Harper government was mortgage lending standards (such as maximum amortization period and maximum loan-to-value ratio). The government allowed mortgage insurers to significantly loosen these standards in 2006. This freedom not only exacerbated already strong housing investment through 2006-08 but greatly increased the risks to financial stability. The government reversed course two years later, thereby reducing the risks of financial instability and correcting the error made earlier.

From July 2007 to January 2009 the Harper government played an important role in effectively managing the asset-backed commercial paper crisis so that it did not spread to other parts of the financial markets. In 2009, it also managed well the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation securitization of bank-held mortgages. This action helped to prevent an extreme squeeze on the capacity of Canadian banks to lend, which banks in the United States and Europe experienced during the height of the financial crisis. Because of these actions and because, even more importantly, Canadian banks had been well managed and regulated for many years, the federal government did not have to use up fiscal room to bail out the banking system. Budgetary deficits that were incurred in 2009-10 directly increased domestic demand and prevented a more serious collapse in Canadian output and income.

After 2009, the federal government moved to tighten regulation of financial institutions. This undoubtedly reduced the risk of future banking crises. However, it also reduced banks’ capacity to lend, although the price and nonprice lending conditions offered by banks still improved in 2010-14 and stabilized in 2015, according to the Senior Loan Officer Survey conducted by the Bank of Canada.

Following the crisis, the federal government moved to establish a national securities regulator with a goal of improving the functioning and stability of financial markets, and in particular fixed-income markets, which globally had performed disastrously prior to and during the crisis. While its initial attempt was rebuffed by the Supreme Court, a cooperative federal-provincial capital markets regulatory authority is now (2016) in the process of being created. This new authority should not only reduce the risk of future instability but also improve market efficiency and hence contribute to growth.

On macroprudential policy, therefore, the federal government during the Harper years continued to strengthen previous governments’ policies to promote a stable financial sector, although unfortunately with a more rules-based approach to prudential supervision as opposed to our previous principles-based approach. The initiative of creating a capital markets regulatory authority jointly with several provinces was an innovative step toward promoting a more stable and efficient financial sector.

Structural policy: Promoting long-term growth

Having discussed the macroeconomic overview of the Harper government years, as well as policy choices on the goal of stabilization, we can now turn to the second important economic role of the federal government, which is to implement a structural policy framework that fosters maximum long-term growth, thereby supporting a durable improvement in the living standards of Canadians. The goal is to promote increases in the size of the pie to be shared by Canadians.

Some aspects of this structural policy framework affect incentives and resource allocation across a wide spectrum of markets and industrial sectors: tax policy, trade policy and competition policy, for example. Others are aimed at particular markets, such as labour market policy and financial market policy. Still others are aimed at particular industrial sectors: policies related to transport and communications, oil and gas, and agriculture, for example. The Harper government was active in all these policy fields, but in this section we confine our review to policies on tax, labour market, competition, trade, industrial policy (oil and gas) and infrastructure.

Taxation

The structure of taxation in Canada is set largely by the federal government. Tax policy is perhaps the most important policy lever that the federal government has to influence long-term growth. The Harper government was very active both in modifying the structure of taxation and in reducing the level of federal taxation.

Here we confine our review to a few key issues.

While greatly reducing taxes overall, the Harper government decreased its relative reliance on broad-based consumption taxes and increased its relative reliance on income taxes. (Between fiscal years 2005-06 and 2014-15, federal tax revenues fell from 13.3 percent of GDP to 11.6 percent. At the same time, the share of federal revenues represented by taxes on goods and services, largely GST, fell from 21 to 17 percent.)

This broad structural shift, which reversed the thrust of the Mulroney government tax reform, was somewhat detrimental to long-term growth because it limited the scope for reductions in personal and corporate income taxes that would have been more favourable to long-term growth than reductions in consumption taxes. Notably, some of the high effective marginal rates of personal income tax (and rates of clawback of personal transfer payments) could have been reduced more had the GST rate not been reduced from 7 to 5 percent. Lower effective marginal rates of income tax would have enhanced incentives for individuals to work and save. Importantly, however, the federal government provided the incentives needed for Ontario to join the harmonized sales tax, thereby enhancing economic efficiency.

The Harper government introduced a large number of micro tax measures that should have somewhat strengthened tax compliance and in so doing generated fiscal savings for the government. (See table A5.4 of the 2015 budget document for the list of integrity tax measures introduced since 2010.) Moreover, it announced in the 2013 budget the rationalization of several business tax preferences over the subsequent several years.

Overall, these measures should buttress the integrity of the tax system, although the reduction in the small business tax rate announced in the 2015 budget certainly does not.

On the other hand, the Harper government introduced a large number of “boutique” tax preferences targeted to special groups (such as transit and sports equipment credits). These introduced unwarranted complexity and inefficiency into the system. A reduction of general rates of comparable magnitude would have been economically (although not necessarily politically) preferable.

The Harper government introduced on a restricted basis two measures that began to fundamentally change the structure of the personal income tax system: income splitting and the tax-free savings account (TFSA). On income splitting, the government first permitted pension income splitting, effective as of the 2007 tax year. Then in October 2014 it announced limited income splitting for couples with children under the age of 18, effective as of the 2014 tax year. These income-splitting measures have resulted in a partial shift from an individual-based system to a family-based one for certain groups but not others, while leaving in place the progressive rate structure designed for individual-based taxation. Whether the individual-based system is preferable to a well-structured family-based one is a matter of debate, but it is clear that by introducing limited income splitting the Harper government has left Canada with a hybrid system in urgent need of reform.

A second measure of equal fundamental significance was the introduction of the TFSA in January 2009, ostensibly to increase the incentive for working individuals to save for retirement. While this provision is a clear gift to higher-income older workers and seniors who have accumulated substantial savings in nonregistered accounts, there is little evidence that it has increased or will actually increase household saving. What is clear is that many individuals now face a difficult choice as to which form of registered vehicle is likely the most tax advantageous, TFSA or RPP/RRSP. Moreover, to the extent that moderate-income workers today use the TFSA rather than the RPP/RRSP as a registered savings vehicle (and thus will have nontaxable income in retirement), the integration of the tax and Old Age Security/Guaranteed Income Supplement system has been broken. (The old age transfer system — in particular the clawback provisions in OAS and GIS — is predicated on the simple base of income for tax purposes, with no asset test. Because the TFSA will not generate income for tax purposes, some modification of the eligibility rules for the GIS — such as an asset test — may be needed.)

With the introduction of the TFSA — and the increase in the annual contribution limit to $10,000 contained in the 2015 budget — the Harper government created a muddled retirement savings and income support system with perverse incentives, a system that cries out for reform by governments in the future.

In summary, the Harper government tinkered with the structure of the tax system, introducing major measures based largely on political philosophy and many boutique provisions based on narrow group interests. It did reduce the GST rate, thereby giving some boost to household consumption, particularly for lower-income groups (see the later section on income redistribution). It also reduced corporate and personal income tax rates somewhat, thereby improving economic efficiency and long-term growth. What is unfortunate from the point of view of economic efficiency is that the revenue lost through the reduction of the GST from 7 to 5 percent limited the ability of the government to further reduce marginal effective rates of income tax.

Labour market

The Harper government introduced measures that aim to affect labour market behaviour and could enhance potential growth as a result. One was new EI rules in 2013 that clarify what a reasonable job search for suitable employment means and that aim to reduce repeat use of EI through more stringent job-search criteria. Another was to prohibit federally regulated employers from setting mandatory retirement ages, starting in 2011. A third one was to raise to 67 the age of eligibility for the OAS. These last two measures have the potential to raise labour force participation of older workers. A fourth one was the introduction in 2007 and enhancement in 2009 of the Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB), which aims to help overcome work disincentives created by the high effective marginal income tax rates faced at low earning levels. The WITB also has significantly affected progressive income redistribution (see below). Finally, it should be noted that the Harper government’s support to post-secondary education and research moves in the direction of improving productivity growth and hence the longer-term economic outlook for Canada.

Competition

The record of the Harper government in competition policy is mixed. In the area of telecommunications, it worked hard to increase competition in the market for cellular services by reserving spectrum for players other than the big three. It also lifted foreign investment restrictions for telecommunications companies that hold less than 10 percent of the telecommunications market. These measures may improve competition and increase efficiency, although there is only limited evidence that this has occurred. On the other hand, the government took no action to reduce the restrictions (such as cabotage) on competition in the airline industry.

The government continued previous governments’ supply management policies to protect our inefficient dairy and poultry industries and to deny them access to foreign markets. This unwillingness to tackle dairy and poultry competition undermined the government’s ability to secure trade deals, which would enhance the efficiency of Canadian business and stands in sharp contrast to its successful efforts to end the monopoly of the Canadian Wheat Board. Moreover, in the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, “compensation” promised to dairy producers would totally eliminate any efficiency for the sector or benefits to consumers. Finally, the government showed surprising willingness to restrict foreign investment in Canada, such as in oil sands and potash. While the rhetoric of the Harper government was decidedly pro-consumer and pro-competition, overall its domestic policy actions appear to have accomplished little in terms of increased competition in Canada.

Trade

Like the Mulroney government, in principle and in rhetoric, the Harper government was decidedly in favour of trade liberalization. Trade liberalization is favourable to long-term growth because it enhances competition in the domestic market and facilitates access of Canadian exporters to foreign markets. Both effects tend to stimulate labour productivity growth. The Harper government’s record in trade negotiations was somewhat trade and growth enhancing. This government secured an important agreement with the European Union, although some hurdles still remain as we move along the road to implementation. It also affected (a little late) a major free trade agreement with South Korea. While this is an important achievement, it should be recalled that this agreement allowed Canada only to catch up with the United States, which had completed its negotiation with Korea several years earlier.

Not having secured a bilateral trade agreement with Japan, the Harper government entered late into negotiations between the United States, Japan and other Pacific nations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement. As we write this chapter, it is too early to assess the impact that the agreement would have if ratified and what effect the adjustment expenditures for the automotive and supply-managed (dairy, poultry) industries would have on Canada. What is clear is that for both the Harper government and the Canadian economy, the option of not being part of the TPP was far worse than accepting the terms of an agreement negotiated largely among the United States, Japan and other countries.

It is particularly unfortunate that the Harper government shunned suggestions from the Chinese to engage in negotiations for some form of Canada-China free trade agreement. In this regard, Canada has fallen behind Australia and New Zealand in securing access to the world’s second-largest market.

Overall, the Harper government was long on rhetoric in favour of liberalized trade agreements, but short on both the expenditure of political capital and the application of negotiating muscle to achieve greater concrete results during its mandate.

Industrial policy

All governments adopt policies (either explicitly or implicitly) that tend to favour expansion of industries or sectors of the economy that are perceived to be most important for further growth. For much of the quarter-century prior to 2005, federal governments pursued policies with a mild bias toward manufacturing and processing sectors (especially high-tech industries). They also continued to maintain policies highly favourable to mining. The Harper government dramatically changed this policy bias.

Following the stated objective of making Canada a global energy superpower, policies of the Harper government were directed toward the development of the oil sands. A number of technical income tax preferences favourable to the mining, oil and gas sectors were maintained and extended. Pipeline construction was encouraged, and until near the end of its tenure, the government was reluctant to tighten safety regulation on oil shipment by rail. The Harper government failed in its clumsy efforts to promote Keystone XL in Washington, DC, and in doing so drew down on the limited goodwill of the Obama administration to deal with other economic issues important to Canada.

Most importantly, the Harper government did not impose environmental regulations that would increase the cost of extracting and processing bitumen from the oil sands. Consistent with his preelection promises, Harper rejected out of hand any form of carbon tax. In general, the government adopted the stance that Canada would not meet previously endorsed greenhouse gas reduction targets and would not agree to even moderately restrictive targets over the next decade. While many in the oil industry viewed these environmental policies as favourable to oil sands development, clearly they were viewed by customers abroad as inappropriate and thus have reduced foreign (in particular, American) willingness to purchase Canada’s “dirty oil.” As an approach to marketing Canadian oil abroad and securing agreement for pipelines within Canada, these environmental policies were totally unhelpful during the Harper years and will continue to make it more difficult to market Canadian bitumen for many years to come.

It is clear that federal (and Alberta) policies were designed to accelerate the pace of oil sands development from 2006 to the first half of 2014, precisely the period during which rising prices of crude oil were already providing the incentive for accelerated investment in the oil sands. (This was true except for the brief period in 2008-09 when global prices fell.) The combination of federal “energy superpower” regulatory and tax policies exacerbated wage and cost pressures in Alberta that were already severe and further contributed to the strength of the Canadian dollar. During the period of high oil prices and favourable terms of trade, these federal policies may have contributed marginally to overall growth in Canadian output and incomes (labour market and other capacity constraints in Alberta would have limited the gains) but definitely had the effect of fostering a more unbalanced industrial structure. Across the economy as a whole they had a negative impact on cost competitiveness (see figure 7).

Infrastructure

Infrastructure investment results in efficiency gains in the private sector and hence buttresses long-term growth in Canada. Net acquisition of new fixed capital by the federal government in relation to Canadian GDP, although rising in 2008-10, remained modest during the Harper years relative to the period preceding the fiscal consolidation years of the Chrétien government. By contrast, provinces and municipalities increased their new capital spending in relation to the Canadian GDP during the Harper years, compared to earlier periods. By 2013, they would have accounted for 46 percent and 40 percent respectively of total infrastructure investment in Canada against only 14 percent by the federal government (even after taking into account federal transfers to other levels of government for infrastructure, according to Ontario Budget 2015, p. 307). This information suggests that the federal government underspent on infrastructure during the Harper years, directly or indirectly, and after 2011 could have provided greater support for provincial and municipal spending on infrastructure, especially since the federal government was the lowest-cost borrower of all governments.

Income redistribution

Governments are expected not only to help increase the size of the pie to be shared by their citizens but also to ensure that the pie is distributed appropriately among them. This involves income redistribution through taxes and transfers toward lower-income groups. Governments affect household income distribution directly and indirectly through a wide range of transfers and taxes, but mainly through their transfers to persons and their personal income taxes. Governments can also affect real income distribution through changes in the levels and structure of sales and excise taxes and the credits related to these taxes.

The Harper government implemented several measures with potentially favourable distributive impact on lower-income groups, of which four are probably the most important. First, the federal government maintained the GST credit level when it reduced the GST rate from 7 to 6 percent in July 2006 and to 5 percent in January 2008. It also introduced the Universal Child Care Benefit in 2006, a taxable universal benefit of uniform amount provided to parents of children up to the age of six. In 2007 it launched a new Child Tax Credit of uniform amount for each child under 18. (In Budget 2015, the universal child care benefit was increased, especially for children under six, and replaced the child tax credit.) Finally, the Working Income Tax Benefit introduced in 2007 and enhanced in 2009 provided a wage subsidy to persons at low earnings levels who face high effective marginal tax rates if at work.

Estimating the impact of government taxes and transfers on income redistribution is a complex exercise that is beyond our range of expertise. In their contribution to the IRPP volume Income Inequality: The Canadian Story, Andrew Heisz and Brian Murphy worked out such estimates for Canada for the period from 1976 to 2011, the last year for which they had the microdata necessary for their calculations. From our perspective, their key finding is that income redistribution toward lower-income groups through federal and provincial taxes and transfers tended to increase modestly during the Harper years of 2006-11, relative to the first half of the 2000s. No doubt federal taxes and transfers played an important role in this increased redistribution, although Heisz and Murphy do not factor into their calculations the effect of the reductions in the GST rate implemented by the Harper government. Their results indicate that the increase in income redistribution was due entirely to transfers, the effect of which on redistribution rose to markedly higher levels over 2009-11.

Heisz and Murphy estimate that income inequality before taxes and transfers tended to rise slightly over 2006-11 but that income inequality after taxes and transfers remained the same. Thus, redistribution through taxes and transfers fully counteracted the rise in income inequality due to market forces.

What we take from these results is that the Harper government contributed to an increase in income redistribution in favour of lower-income groups during the 2006-11 period, in part by beefing up child benefits and further increasing the overall progressivity of the tax system, even as average tax rates were falling. This redistribution counteracted a small increase in market income inequality (before taxes and transfers) in Canada over this period.

Low-tax balanced-budget objective

In pursuing its fundamental objectives of stabilization, long-term growth and income redistribution, any central government must ensure that its debt remains on a sustainable path. The Harper government made the pursuit of an annual balanced budget a primary element of its economic agenda. It went further than targeting a lower debt-to-GDP ratio. A balanced budget with lower taxes was the key strategy for the medium term. And this the Harper government did achieve.

However, this accomplishment was made possible in large part by the reduction in the tax revenues needed to finance the dramatically lower public debt charges that came out of Chrétien-Martin budget surpluses from 1997 to 2005, and the sharp fall in global interest rates — neither of which was the result of Harper government actions.

Tax revenues during the 2006-14 Harper years represented about 12 percent of GDP compared to about 13.5 percent during the Chrétien-Martin years (1993-2005), while at the same time federal program spending actually increased marginally, from 12.8 to 12.9 percent. Over the period from 2006 to 2014, the Harper government ran a deficit of 0.8 percent of GDP on average, but this was small enough that the net debt-to-GDP ratio of 31 percent at the end of 2014 was lower than the 36 percent it had inherited from the Martin government at the end of 2005. Thus, even if it did not deliver on the growth objective, the Harper government did deliver on its low-tax balanced-budget promise while actually increasing program spending slightly as a share of GDP.

The fact that the Canadian federal government has remained in much better fiscal shape than any other G7 central government is an achievement of the Harper government. We note that, as it went to the polls in October 2015, the Harper government left behind underfunded directly delivered federal programs (such as defence and Aboriginal health) and a revenue system that relied overly on strong resource prices to buttress personal and corporate income tax revenues. With slowing growth due to an aging population and lower resource prices, this legacy will make it very difficult for any future federal government to deliver a public debt performance similar to that delivered by the Harper government in 2011-15.

Summary and conclusion

Relative to the 1984-2005 period, Canadian economic performance during the Harper government years worsened on most aggregate measures of growth and jobs, despite the fact that it was much better than American performance in 2007-11. On the other hand, relative to the earlier period, the growth rate of real disposable income per capita in Canada during the Harper years was much faster. Income growth per capita was also double the rate in the United States over 2006-15.

Canadian macroeconomic performance during the Harper government years was driven largely by global economic developments; federal economic policy initiatives played a relatively minor role in shaping Canadian performance, except during 2008-10. A severe US recession and sluggish US recovery along with a sizable loss of Canadian cost competitiveness depressed Canadian growth. The drag was offset only partly by the positive effects of stronger prices for commodities and lower global and domestic interest rates. The resilience of the Canadian banking system and the relative buoyancy of the Canadian housing market, which owed little to Harper government policies, helped to preserve financial stability and buttress economic growth, in contrast to what happened in many other advanced economies.

Contributing effectively to stabilization with discretionary fiscal policy is a difficult task. The federal government ran an overly expansionary discretionary policy in 2006 and 2007, a fortuitously but appropriately expansionary policy in 2008 and an appropriately very expansionary policy in 2009-10. Because it was too focused on reducing deficit over 2011-15, its policy contributed to an unnecessarily slow, rather muted recovery in Canada.

There are many channels through which a government can foster long-term growth, including taxation, measures affecting labour market behaviour and product competition, trade policy, industrial policy and investment in infrastructure and research. The Harper government took policy action in all these areas with mixed results. Reductions in the effective rates of personal and corporate taxation were favourable to long-term growth. However, a decreased reliance on broad-based consumption taxes, whose rate was cut twice by the Harper government, was somewhat detrimental to long-term growth, both because it limited the scope for reductions in personal and corporate income taxes that could have taken place otherwise, and because it limited growth-enhancing expenditures.

Changes in the structure of employment insurance and a future rise in the retirement age for the Old Age Security program, if these were to be maintained by subsequent governments, would improve the functioning of the labour market over the longer term. Changes in the regulation of financial markets and institutions will enhance financial stability and market efficiency. On the other hand, the record of pro-consumer competition policy was decidedly mixed. Actions on trade policy, though slow in implementation, should contribute to future growth. Action in foreign investment review was confused and created uncertainty, and that uncertainty will likely constrain future investment and hence lead to slower growth.

With the exception of 2009-10, the Harper government underspent on infrastructure, thereby constraining future growth. Policy on development of the oil sands and related environment policies fostered unbalanced growth over the last decade.

The Harper government contributed to a modest increase in income redistribution toward lower-income groups in the 2006-11 period, in part through beefing up child benefits and maintaining the GST credit while cutting GST rates. In so doing it helped prevent an increase in inequality in disposable income (after taxes and transfers), as occurred in market incomes.

Finally, the Harper government did deliver on its low-tax balanced-budget promise while actually increasing program spending. This accomplishment was facilitated by the greatly reduced public debt charges that arose from budget surpluses in 1998-2005 and a sharp fall in interest rates — neither of which was the result of Harper government actions.

In any period, a central government faces trade-offs when deciding which economic objectives it should prioritize. The Harper government made four major choices that brought some benefits but inevitably entailed costs in the form of sacrificed opportunities:

- Lower taxes in relation to GDP worked toward supporting long-term growth but also lowered levels of public services that could otherwise have been provided directly or indirectly (for example, via transfers to provinces).

- A lower GST rate (while keeping the level of GST credit) helped redistribute income toward lower-income groups but deprived the government of revenues that could have better financed public services directly and indirectly and provided more support to long-term growth through lower marginal income tax rates and increased spending on growth-enhancing physical and human infrastructure.

- Trying to achieve a balanced budget strengthened the already strong federal fiscal position, but it did so at the cost of appreciably weaker economic growth at a time of significant slack in the economy in 2011-15.

- Harper government policies, by favouring the development of the oil sands and neglecting environmental regulations, likely contributed indirectly to Canada’s loss of overall cost competitiveness.

The Harper government promised a low-tax, balanced-budget plan that could grow jobs and increase output and income. The government delivered better per capita real disposable income growth than its predecessors, but worse employment and output growth. And this record was determined largely by factors other than federal policy. The Harper government’s economic policies during 2006-15 met the objective of a strengthened fiscal position without sacrificing the goal of income redistribution, but had decidedly less success in meeting the goal of jobs and growth. In the end, a verdict on the degree of success of the Harper government’s economic policies hinges on the relative values that one attributes to the various economic objectives. In our own judgment, after 2010 the Harper government unduly sacrificed growth in order to improve a debt position that was already solid.

Photo: Sean Kilpatrick / Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.