It seems like only yesterday that the newly elected President Barack Obama strode onto the well guarded stage in Grant Park, Chicago, to deliver his victory speech. The bright lighting in the park and the general feeling in the air as conveyed by TV camera shots of members of the crowd, including a teary-eyed Oprah Winfrey leaning on a stranger, made us all feel that this was a historic moment. The first African American had just been elected president of the United States of America.

The world listened as the young president-elect began his delivery and soon reminded the crowd that “this victory alone is not the change we seek.” He went on to describe a need for a “new spirit of service, a new spirit of sacrifice” and reiterated his campaign commitment to “healing divisions” and bringing about a “new dawn of American leadership at home and around the globe.” He closed by repeating his campaign slogan, “Yes we can!” It was heady stuff.

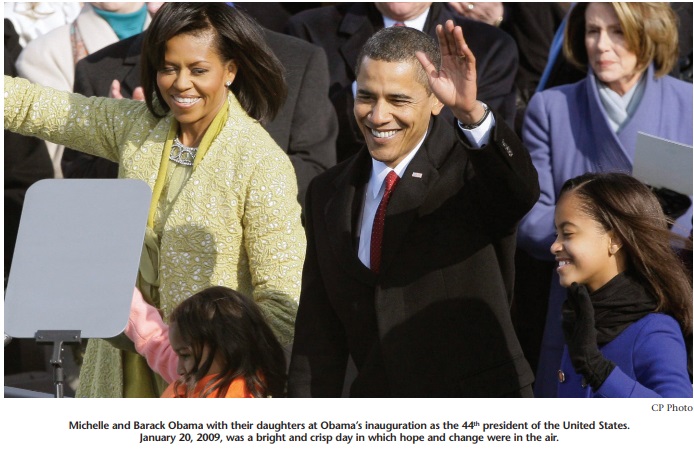

On January 20, 2009, the inauguration of Barack Obama occurred in a setting where the level of anticipation in the crowd could not have been greater and the hopes could not have been higher on a cold, sunny day. The nation was caught up in the euphoria of change, and the belief that a new generation of leadership was emerging. After eight years of the “war on terror,” two wars being waged in Iraq and Afghanistan, a near repeat of the 1930s Great Depression, it seemed like a cathartic moment and the advent of a transformational presidency. Shortly after, voter approval of the new administration hovered in the high 60s. America was on a new voyage, so we thought.

It has been nearly two years since Obama won a decisive victory, not only in the Electoral College but also for the Democratic Party in Congress. This had all the ingredients for an activist presidency: a clear mandate for change, an ambitious agenda and the means to accomplish it. However, things have not quite worked out as anticipated. On the eve of this year’s midterm elections, President Obama’s approval ratings have fallen to the mid-40s. The best prognosticators in the business (Charles Cook and Stuart Rothenberg) are predicting massive losses for Democrats, with a majority of pundits going as far as to concede the House of Representatives to the Republican Party. The Senate may still be a possibility for the GOP.

To be fair, history records that voters are not kind to presidents during mid-terms, as Gil Troy points out elsewhere in these pages. Since the end of the Second World War, only George W. Bush and Bill Clinton (1998) were able to improve their party’s standing at the midterm elections, and that can be attributed to the effects of 9/11 for Bush, and to voter disenchantment with impeachment proceedings for Clinton. All other presidents since FDR saw their party lose seats. Over the past 17 midterms, the average loss in the House of Representatives is 28 seats and 4 in the Senate; is the latter number being attributed to the fact that only one-third of the Senate is at each stake at election time.

Despite the odds of history working against an incumbent president in the midterm showdown, what is particularly noticeable is the changing mood of the country since Obama spoke on that Chicago night of November 4, 2008. It became obvious in a short period that the American voters were more preoccupied with their economic security than with history making or the promises of their new leader. Over 7 million jobs had been lost since the recession of 2007 began, with many homeowners facing foreclosures, as the length of unemployment was increasing as never before since the Great Depression; there were also persistent fears of a meltdown of the financial system.

It soon became evident that voter patience had its limits and Americans wanted “Obama the president” to provide a quick solution on jobs and the economy rather than listening to “Obama the candidate” pushing an array of different issues from health care to climate change. As Democratic strategist James Carville so aptly said in another time (1992): “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Even the most rabid detractors of Barack Obama admit that he has been an activist president — and has delivered results in an extremely challenging political environment. Conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer recently cautioned the Republicans not to underestimate Obama. It is difficult to find a more substantial legislative record in the first 18 months of a presidency since the days of Roosevelt. If anything, this president took on too much, may have communicated too little and, by delegating to his congressional leaders the details of his signature legislation, disappointed some of his political base. As he indicated in his inaugural address, he committed to tackle the economic problems facing the nation, initiate stronger regulations regarding the financial system and its security, offer possible relief for the middle class, reform education and health care, fight for energy independence and climate change provisions, work to end nuclear proliferation, wind down the war in Iraq, combat the continuing threat of terror and reduce the tension in the Middle East. This was quite an agenda he laid out at a time of great economic uncertainty, and a risky one at that.

It was not long before Obama had to deal with the Somali pirates’ takeover of an American vessel on the high seas, and cases of homegrown terrorism were added for good measure. The BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico confronted the President with the worst environmental disaster in US history, sidetracking his agenda for several weeks. Policy intentions are one thing but in the real world, stuff happens.

But politics is not always predictable or certain. It was not long before Obama had to deal with the Somali pirates’ takeover of an American vessel on the high seas, and cases of homegrown terrorism were added for good measure. The BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico confronted the President with the worst environmental disaster in US history, sidetracking his agenda for several weeks. Policy intentions are one thing, but in the real world, stuff happens.

This has not been an easy presidency and the slow economic recovery has done nothing to make it easier. The case for health care reform, with the promise of bringing costs down and providing economic security, would have been easier to make if unemployment had not been at 9.5 percent. By most accounts, this is a historic accomplishment when compared with the efforts over the past century by various presidents. Yet Democrats and Obama will be the first to concede that this major reform has given very little bounce to their approval numbers, despite the magnitude of the reform.

The first and most symbolic legislative achievement of the administration had to do with the economy. Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) the stimulus plan with a price tag of over $800 billion involving middle-class tax relief, infrastructure revitalization and development, investing in emerging sectors (such as green energy) and helping state and local governments to preserve services. In signing the legislation, the administration predicted it would result in bringing unemployment down to 8 percent. It has not. Debates have since raged on between those on the left, like noted economist Paul Krugman, saying it was not enough, to those on the right saying that it was wasteful spending, bringing the return of big government and a high unemployment rate. The increased deficit, the slow job recovery and the rise of the Tea Party (a populist, fiscally conservative libertarian movement) appeared to tip the scales in favour of the opponents and critics of the stimulus package, if we judge by opinion polls going into the midterms.

In truth, the majority of conservative and liberal economists recognize that ARRA may have saved over 2 million jobs and probably prevented a deeper recession, possibly another Great Depression. Nine months of private sector job creation, however, is not convincing enough when nearly one in six Americans is unemployed or underemployed, and many have been out of work for over 24 months.

Another major challenge facing the Obama administration had to do with financial regulation. Since the rise to power of the conservative movement in the United States, deregulation of the financial sector has become a buzzword. Even Democratic President Clinton bought into it, with the result that he agreed to abolish in 1999 the Glass-Steagall Act, which had successfully regulated the financial sector since the days of FDR and the Great Depression. In the summer of 2010, Obama succeeded in signing the most wide-ranging act to regulate the financial sector since the 1930s despite strong opposition from the Republican Party and Wall Street. The tangible impact on the voter remains marginal, however.

There have been three areas where Obama was able to achieve bipartisan support: education, the Iraq war and the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP). Obama has succeeded in bringing the two parties in sync and has garnered kudos regarding education and his Race to the Top program. Even ideological conservatives have applauded his moves to improve schools. And with respect to the war in Iraq, he fulfilled his promise of withdrawing all combat troops by August 31, 2010. While each political party took credit, both agreed with the removal of combat troops.

On the question of TARP bailouts, which began in 2008 under the Bush administration and continued under the Obama administration in the financial and auto sectors, few in the political class doubted their necessity. Most of the money invested in the financial and the auto sectors has been paid back, and both have shown a resurgence. General Motors will soon be privatized after the government takeover of 2009. Despite some real success, however, the voter remains very skeptical about the wisdom of the bailouts.

The majority of conservative and liberal economists recognize that ARRA may have saved over 2 million jobs and probably prevented a deeper recession, possibly another Great Depression. Nine months of private sector job creation, however, is not convincing enough when nearly one in six Americans is unemployed or underemployed, and many have been out of work for over 24 months.

Despite various significant achievements, critics have a point when they assert that the current political context has not produced the basic premise of the Obama candidacy: heal the divisions and change how politics is conducted. Republicans have consciously acted with the discipline of a party in a parliamentary system and have been systematic in their tactics and in their opposition. There has been no bipartisanship on the major initiatives of Obama. Democrats have also dug in their heels and have consequently labelled their opponents as obstructionists and the “party of no.” Meanwhile, the rise of the Tea Party has scared away Republican moderates, with some moderate incumbents being challenged and defeated in primaries. This insurgency within the GOP does not augur well for a change of the political climate.

Finally, on the matter of performance, whether you agree with him or not, Obama has kept many of his promises. Some on the left are disappointed, but they did get some important reforms. The conservative movement has been emboldened with the active support of individuals like TV personality Glenn Beck and the Fox News Network. As a result, the reviews on Obama’s performance can be qualified as mixed. The general assessment two years into the job can be summed up as significant and promising in terms of achievement, but still a work in progress.

Obama’s detractors have spoken of the one term presidency. Supporters speak of a president who was dealt a nearly impossible hand and is turning things around. The attacks will continue to be virulent, with the 2012 election only two years away. Some Democrats have openly distanced themselves from the President in this election cycle, and many have shown a decided reluctance to defend the reforms brought in. But this should be temporary. The Republicans have revived the discourse against big government, and the old conservative mantra from Ronald Reagan that “government is not the solution, government is the problem” has resurfaced. In addition, Representative Paul Ryan (Wisconsin) and a few others have made cogent proposals for dealing with thorny long-term issues like the reform of Medicare and Social Security. After November 2010, they will be focusing on presidential politics.

Three major issues will remain at the top of the political agenda after the November mid-terms: immigration reform, energy/climate change legislation and entitlement reform. All seem stalled by the election season, where polarization, fear and gridlock dominate the political discourse. But, like it or not, the fact that between 12 million and 20 million inhabitants are considered illegal will not go away. Nor will manmade global warming disappear. And the issue of dependence on foreign sources of energy will continue to affect both domestic and foreign policy. With the entitlement programs taking a greater share of government spending and bringing pressure on deficit and debt, expect this subject to be front and centre after November. These difficult issues have obvious ideological currents, but they could provide opportunities for the two parties to find solutions. Voters will become impatient if they observe deliberate political gridlock on issues affecting their daily lives.

We know midterms are primarily about local issues. This cycle will not be any different. But in 2012, it is fair to say, Obama will own the economy as an issue as well as the wars abroad. While foreign policy has not played a big role with the electorate in the first two years, it is probable that this area could have greater impact by 2012.

Obama’s foreign policy team, led by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, has been methodical and efficient and has some promising possibilities on the horizon. The current talks between Israel and Palestine may be fragile, but they are a step forward, coming so early in the Obama presidency. The sanctions on Iran are starting to have some impact but its nuclear ambitions remain a question mark. Here American diplomacy has not been alone, with China and Russia on board with the sanctions. The New START treaty has a solid chance for ratification, once the election is over. And lest we forget, Obama remains highly popular abroad, and the appreciation for the change in tone in US diplomacy is a welcome development around the globe.

Should the predictions of a Republican resurgence in Congress come true, the big question will be: Can Obama operate with substantially reduced majorities, or the loss of one house or two after November? Clearly, whatever the outcome, he will not be in as advantageous a position as he was in 2008. How effective, then, will the socalled bully pulpit be when he will have to depend more on the mood of voters than on votes in Congress to influence the Republicans, who are likely to be emboldened by the gains made in November?

This will be one more test for Obama. His resilience in adversity, his capacity to rebound and his characteristic coolness will face greater challenges and pressures than ever in his political career as he prepares for his final election campaign. The mood in America is anywhere from morose to sour, and in the short term, the one political figure who can best impact this climate is the President. In a curious way, Obama’s appeal in 2008 was the possibility of a transformational presidency, but his success in 2012 may well depend on how good a transactional president he can be.

Photo: Everett Collection / Shutterstock