(Version française disponible ici)

In early 2022, the capital of a G7 country was paralyzed by a few hundred protesters who arrived with their trucks. Ottawa was under siege, and the federal, provincial and municipal governments seemed completely overwhelmed.

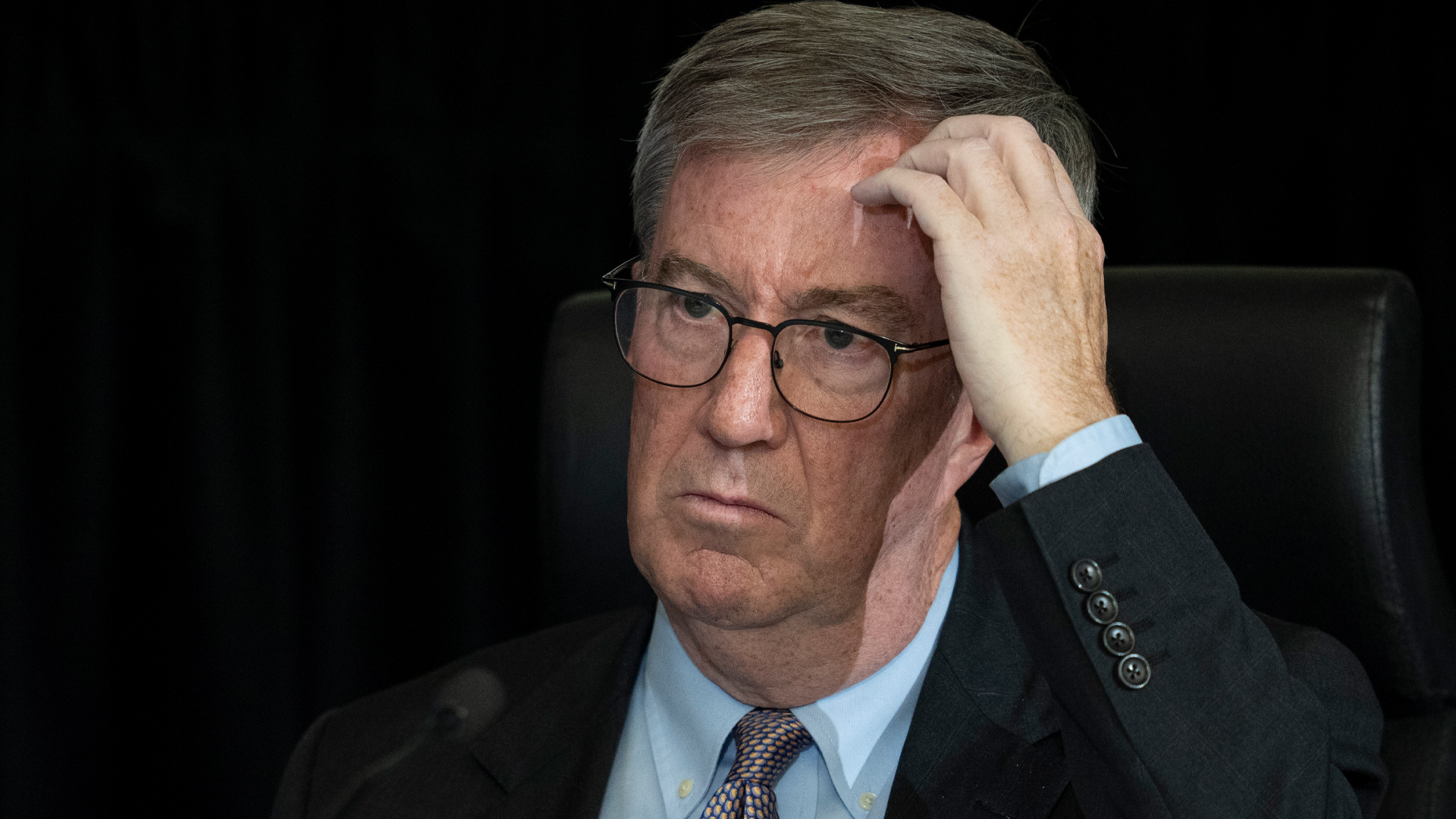

How could this happen, and what lessons in governance can we learn from the public authorities’ response to the “Freedom Convoy”? The findings of the Public Order Emergency Commission, chaired by Commissioner Paul Rouleau, suggest some possible remedies to strengthen governance mechanisms so that our government authorities can better respond if similar events occur again.

We will focus on two aspects of public governance that, according to the commissioner’s analysis, contributed to plunging the country into a major avoidable crisis. The first is the complex relationship between the city, the province and the federal government during the events, which led the commissioner to conclude that there had been a ‟failure of federalism”. The second, which has gone somewhat unnoticed, is the corporate governance that was illustrated by the messy and chaotic relationship between the Ottawa Police Services Board and the Ottawa Police Service at the outset of the crisis.

Apathetic governments

In the third volume of his final report, Commissioner Rouleau severely criticizes the lack of communication and consistency between the federal and Ontario governments and the City of Ottawa. In his view, the scale of the crisis could have been reduced, and the use of the Emergencies Act avoided, if public authorities had co-operated better in enforcing existing laws.

It must be said that the context itself was confusing, which partly explains the apathy of public policymakers. The demonstrators occupied Wellington Street, a highly symbolic location directly opposite the Canadian Parliament, even though the management of this street is normally the responsibility of the City of Ottawa.

The main target of the demonstrators was the prime minister of Canada, who was criticized for requiring truckers to be vaccinated in order to enter the country, whereas health measures are generally imposed by the provinces. Finally, the federal government was faced with a dilemma between citizens’ legitimate right to protest, maintaining public safety and the smooth functioning of the economy and trade with the United States.

In retrospect, the various levels of government took no responsibility for managing the crisis. The federal government blamed the provincial government for not having grasped the magnitude of the situation. The provincial government expressed frustration with the way the City of Ottawa’s chief of police and then-mayor Jim Watson had handled the situation, and with the federal government for failing to mobilize the necessary resources. According to Ontario Premier Doug Ford, management of the convoy was a national rather than a provincial issue. Municipal representatives blamed both the premier of Ontario and the prime minister of Canada for not sufficiently sharing intelligence information or mobilizing their respective police forces.

For his part, Commissioner Rouleau points to communication problems between the intelligence services of the Ontario Provincial Police and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which had disastrous consequences for co-ordination and co-operation between the players. In particular, the commissioner notes that the RCMP provided conflicting information to other police forces. He also noted inconsistencies in information collected on social media and in open-data sources.

Confused municipal authorities

It didn’t get any better on the municipal front. Commissioner Rouleau and, shortly before the release of his report, the City of Ottawa’s auditor general, who produced a very interesting report on the city’s management of the crisis, observed serious co-ordination and communication problems and misunderstandings between the police service, elected officials and city administrators.

READ MORE FROM THE SERIES

Peaceful assembly rights should not protect protests that cause fear of violence

The Rouleau report and the politics of living next to a powerful neighbour

Perspectives on the Ottawa convoy protest and the Rouleau commission report

Legal tussling over the Emergencies Act is far from over

Firstly, elected officials were not all on the same wavelength, and we now know that there was also friction within the police department itself. From a governance perspective, there are also serious questions about the role of the City of Ottawa Police Services Board, which could have played a more decisive role as a crisis unit, given that it is supposed to oversee the actions of the police service and that it is made up of both municipal councillors and community representatives appointed by the province and the city.

So why was the Ottawa Police Services Board unable to play a key role in the risk analysis and management of this crisis? All reports indicate that at the time of the incident, the board had a confused understanding of its own role in the crisis. Its ability to provide adequate civilian oversight of the Ottawa Police Service was restricted by the police service’s own resistance to providing relevant information it requested in order to play its role.

The commission should have ensured that the police had contingency plans in place in case the protest turned into a longer occupation. In his report, the commissioner concluded that the commission’s terms of reference authorized him to order the police department to provide more information. In other words, the commission should have assumed a greater role in crisis management and in the governance of emergency measures.

How do we avoid another failure?

In short, public players at all levels completely failed to take measure of the situation and react quickly. They let the convoy protesters settle in beyond the first weekend, with the consequences we now know. From a governance point of view, we must remember the absolute confusion in roles and responsibilities, the lack of accountability and the communication problems.

Who is responsible for what when such a crisis occurs? And what are the mechanisms to foster co-operation? Commissioner Rouleau’s report offers suggestions for the future.

Better information gathering, sharing and co-ordination

The commissioner suggests that the federal government work with other stakeholders to develop or strengthen protocols for the sharing, collection and dissemination of public safety information. This includes clarifying who is responsible for collecting, analyzing and distributing information in the event of a major event, and improving the ability to assess the reliability of information while respecting the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the protection of privacy.

Such protocols should also aim to ensure compliance with legislative mandates, better monitor social media and open-access information, and ensure that detailed and reliable information is shared between police forces. The commissioner also proposes that stakeholders agree to designate a national intelligence co-ordinator for events whose scale exceeds a single province or territory. Finally, the commissioner recommends that all governments and their respective police forces work together to develop pan-Canadian standards for dealing with major events of national, inter-provincial or inter-territorial dimensions.

Improve oversight and governance of police services

Commissioner Rouleau also offers some interesting avenues for improving civilian oversight and governance of police services. He acknowledges that the Ottawa Police Services Board did not have the information it needed to carry out its duties, and that its police service did not understand (or recognize) the extent of the responsibilities the board had to assume. This confusion resulted in part from an overly broad interpretation of the prohibition on interference by a commission in the day-to-day activities of the police.

[wd_hustle id=”20″ type=”embedded”/]

In this regard, the commissioner recommends that all provincial police services boards clarify their oversight and governance role for major incidents. At a minimum, policies should explain what constitutes a major incident, identify best practices for policing within their jurisdiction, differentiate between planned (normal police oversight) and unplanned events (such as a crisis), define the scope of prohibitions on interference with day-to-day operations, and clarify the role of commissions in supporting requests for additional resources from other levels of government.

Commission members should also receive better training on their roles and responsibilities in crisis management so as not to be caught unprepared. It may be necessary to create local procedures to clarify the role and responsibilities of police services boards vis-à-vis police services in crisis situations.

Three lessons in governance

In short, the Rouleau report offers three lessons in crisis management governance. The first is that public authorities become vulnerable when they fail to work together. The second is that roles and responsibilities must be clarified between different levels of government before major events occur. The third is that our public institutions must be better equipped to anticipate and manage risks in the future.

This article is part of the Lessons from the Rouleau Commission special feature series.