Sadly, it has taken hundreds of COVID-19 deaths for Canada’s long-term residential care to earn another day or two in the spotlight. For the moment we are in high dudgeon, searching for answers. There will be inquiries, finger-pointing and recommendations. Each outbreak and each death have unique elements, but one thing is certain: the calamity is a policy failure that has exposed our values and priorities and placed too many at the mercy of the pathogen.

Public health care is intensely political because how much we spend and on what signals our priorities. The architecture of Canadian medicare, consolidated in the Medical Care Act of 1966, heavily privileges public financing of hospitals and doctors. At the time, Canada had a median age of 25 and only 3 per cent were aged 75 and over. Long-term residential care was barely on the radar, and there were no provincial home care programs.

By 2019 the median age was nearly 41. The 75+ group comprised 7.4 per cent of the population, and the 85+ population, growing at four times the rate of the general population, accounted for 2.2 per cent. Chronic conditions are the new normal, and about a third of people 85 and over have dementia. These needs are not addressed primarily by the work of hospitals and doctors, but by nurses, personal support workers, home care, assisted living facilities and nursing homes.

Governments could have changed the delivery system and the financing rules to reflect the altered landscape. They did not, and as a result it is not your health needs that determine whether and how much the state will pay for your care, but whether the care is delivered by a physician or in a hospital. Only about half of health care services other than hospitals and physicians are publicly financed.

The business model caters to prosperous seniors who can afford high rents and can pay for escalating levels of care offered either by the home or privately arranged. Residents often move in without major needs and age in place.

About 71 per cent of nursing home care is publicly financed, which on the surface suggests that the sector is not one of medicare’s orphans. But these numbers are misleading. First, they do not include the massive amounts of care provided by families: an estimated 80 per cent of community care and 30 per cent of care in institutions. Second, there is a rapidly expanding private sector assisted living and retirement home industry in Canada, which depending on which types of accommodation are included in the bed count comprises an estimated 250,000 units. The business model caters to prosperous seniors who can afford high rents and can pay for escalating levels of care offered either by the home or privately arranged. Residents often move in without major needs and age in place. Many would be nursing home eligible but have the means and the option to privatize their own care. My mother is one of them.

These developments have political and financial consequences. As a general proposition, people will support high levels of public funding for programs they can foresee using, irrespective of income and wealth: hospitals, doctors, freeways and at least for now schools. Where enough people abandon the public system for a private option – schools in Australia are an example – support for the public alternative will tend to decline among the politically important middle class and upper-middle class people who no longer anticipate being clients.

This dynamic is at work in nursing homes. There is no active effort to beggar them; their mediocrity is assured simply by the absence of strong political support to provide them with enough resources to make them better. The age and quality of facilities is variable, and less prosperous seniors who far outnumber those able to afford upscale alternatives are left to take their chances in the nursing home lottery. Most homes are owned and operated either by non-profit societies with limited capital or for-profit companies. In both cases there is an incentive to extend the life of the buildings for as long as possible, and to house the maximum number of revenue-generating residents, often two to a room.

No one wants to go into a nursing home and there have been decades-long calls to invest more heavily in home care and assisted living to prevent or delay admission. Northern European governments spend two to three times as much of their GDP as Canada on health and social long-term care. As with residential services, many seniors – including some with limited means – have simply bypassed state-sponsored home care and bought their own, though numbers are hard to come by because the sector is highly decentralized and often informal.

Governments are reluctant both to build massive numbers of new nursing home beds and to spend enough money on community care to reduce the need for them. In countries like Denmark, the social contract makes it the government’s job to provide the care so families can enjoy quality time together. Here in Canada, the families are conscripts and backstops.

Canada’s policies are a reflection of our cultural attitudes. There is nothing glamorous about even high-quality, spacious and pandemic-resistant nursing homes. They are the last stop on the line, full of people in decline, many with dementia, their contributions to the economy long exhausted, the only return on investment a more humane and comfortable death.

The public and non-profit homes cannot compete with children’s hospitals and research institutes for public and philanthropic funding, and the for-profit homes are obligated to their shareholders first. The pay scales for the health care aides who do most of the work are low, the jobs are frequently part-time or casual and the workforce relies significantly on recent immigrants, many of whom work in multiple places to make ends meet. Accounts of staffing shortages, neglect of basic hygiene needs and skimping on supplies elicit temporary outrage but rarely lead to systemic change. All in all, easy pickings for a novel virus.

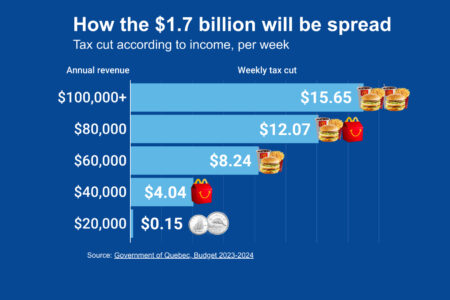

We choose not to tax ourselves high enough to create a first-class long-term residential and community care sector. We tolerate a hybrid public-private system despite the obvious moral hazard of extracting profits from society’s most vulnerable.

This state of affairs is a choice, not an inevitability. We choose not to tax ourselves high enough to create a first-class long-term residential and community care sector. We tolerate a hybrid public-private system despite the obvious moral hazard of extracting profits from society’s most vulnerable. We build, upgrade or replace hospitals where people typically spend a week or less for episodic care faster and at much greater cost than we upgrade the obsolete homes people live in 24/365 for the remainder of their lives.

Canada is stuck in an antiquated model of medicare designed for the country as it was 50 years ago. Today, there are rapidly growing numbers of very old people who need as many non-medical as medical services to remain in the community – the supports for the activities of daily living that governments only grudgingly fund.

Nursing homes are now rightly reserved for very incapacitated people who need a lot of care that can’t be had on the cheap. Maybe the COVID-19 body count will be the scandal too big to ignore, but maybe it won’t. It is no accident that more communitarian political cultures excel at long-term care. Doing right by (mainly) very old and very incapacitated people – and importantly, their families — is redistributive, essentially altruistic and compassionate spending based on dignity and decency. The beneficiaries will not contribute to the GDP. The spending will, all else equal, increase taxes.

It’s ultimately a democratic issue. To date there has been no political price to pay for pushing long-term care down the priority list. Long-term care insurance – where people pay premiums, usually beginning in middle age, to protect themselves against major long-term care expenditures in later life – has thus far had low uptake in the U.S. and there appears to be little interest in it in Europe. It is an unlikely solution because without massive subsidies, it would be unevenly taken up on the basis of class, and given the premiums required to make it solvent, most well-off people are probably wiser to self-insure.

Only significant additional public spending can create uniformly high quality and accessible home care and nursing homes. Canada has a consequential choice to make: either limp along with a hybrid and often minimalist system or raise the bar to what the best of European countries have achieved. It is entitled to turn its back on long-term care, but it cannot avert its gaze.

This article is part of the Facing up to Canada’s long-term care policy crisis special feature.

For related content, check out the IRPP’s Faces of Aging research program.