The Liberal government’s new firearms-control bill, C-21, has received a frosty reception from both proponents and critics of gun control. Advocates argue that allowing municipalities to regulate handguns would create an ineffective patchwork of regulations. They also object to allowing owners of semi-automatic assault-style rifles to retain their newly prohibited weapons.

Amid these significant points of debate, a seemingly minor reform, aimed at tightening the law banning replica firearms, has generated considerable outrage for its possible effect on the “airsoft” industry. Airsoft guns shoot plastic projectiles at low velocities and are often used in games similar to paintball. The exterior appearance of airsoft guns is often based on real firearms. Retailers market some airsoft guns modelled after the AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, a weapon that Ottawa declared a prohibited weapon on May 1, 2020.

However, governments have had to balance the recreational use of imitation firearms against public safety, particularly given concerns expressed by police organizations across the country. The proposal to tighten the ban on replica firearms is a logical step toward ensuring safety for Canadians.

Sellers of airsoft guns modelled on real firearms have taken advantage of a loophole in existing firearm laws. Under Canadian law, it has been illegal to own a replica firearm (other than one that copied an antique) since the mid 1990s. But airsoft guns are not technically replicas because they fire projectiles. Because they shoot at low velocities, they are not technically firearms, either.

Airsoft businesses object to the closing of this loophole and claim Bill C-21 will cause them substantial financial harm. A parliamentary e-petition arguing against this portion of Bill C-21 is now garnering signatures. Conservative critic for Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Shannon Stubbs dismissed the provision affecting airsoft as an irrational effort to ban “toy guns” that “are not responsible for the shootings” that are “causing death in Canadian cities.”

However, there is a long history of efforts to control the use and/or possession of replica firearms that is not about a desire to ban toys. In 1959, the Progressive Conservative government of then-prime minister John Diefenbaker altered the Criminal Code to prevent crimes committed with imitation guns. Davie Fulton, justice minister at the time, said action was needed because “more and more thefts have been committed by bandits who, in order to frighten or overpower their victims, used nothing more than an imitation firearm.” In this way, an imitation firearm “achieves the same result as would a real one.” Fulton found it logical that possession of an imitation weapon “constitutes an offence identical to the possession of a real one.”

Parliament then enacted legislation stipulating that anyone who “carries or has in his custody or possession an offensive weapon or imitation thereof, for a purpose dangerous to the public peace or for the purpose of committing an offence is guilty of an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for five years.” In 1977, the federal government increased the punishment for this offence to 10 years.

This did not end concerns with imitation firearms, however. The Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) strongly advocated for prohibiting imitation firearms rather than just punishing people who used such guns to commit crimes. In 1994, the association passed a resolution complaining of the “considerable number of criminal offences involving the use of replica firearms,” some of which had resulted in the “death of young people.” The CACP added that replica firearms could “cause trauma to victims,” and urged a ban on the manufacture, sale and possession of replica firearms. The Liberal government of that time responded by creating the current law, adding “replica firearms” to the list of prohibited devices.

This did not satisfy the CACP, which in 2000 passed another resolution calling for stronger action on imitation guns. It noted “a proliferation in the illegal use of replica firearms” and claimed that “replica firearms have been used to terrorize victims and compromise the safety of the Canadian public.” The CACP also expressed concern that police officers might use deadly force “in situations where they believe these replica firearms to be authentic.” For example, Nova Scotia’s Serious Incident Response Team recently concluded that RCMP were justified in shooting a man who threatened his mother with an imitation handgun, then pointed the device at police.

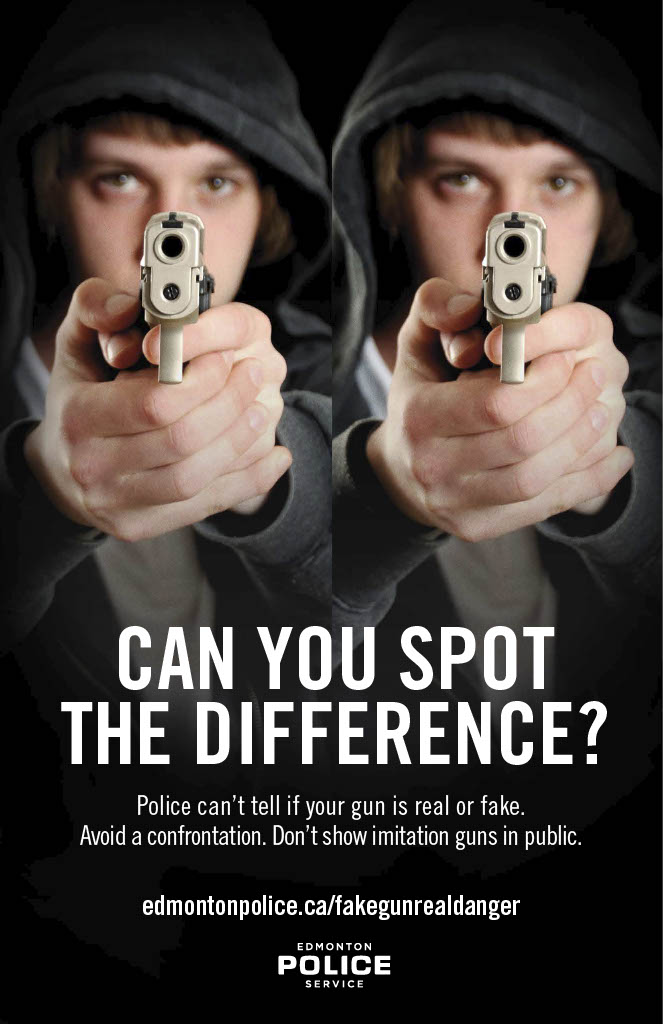

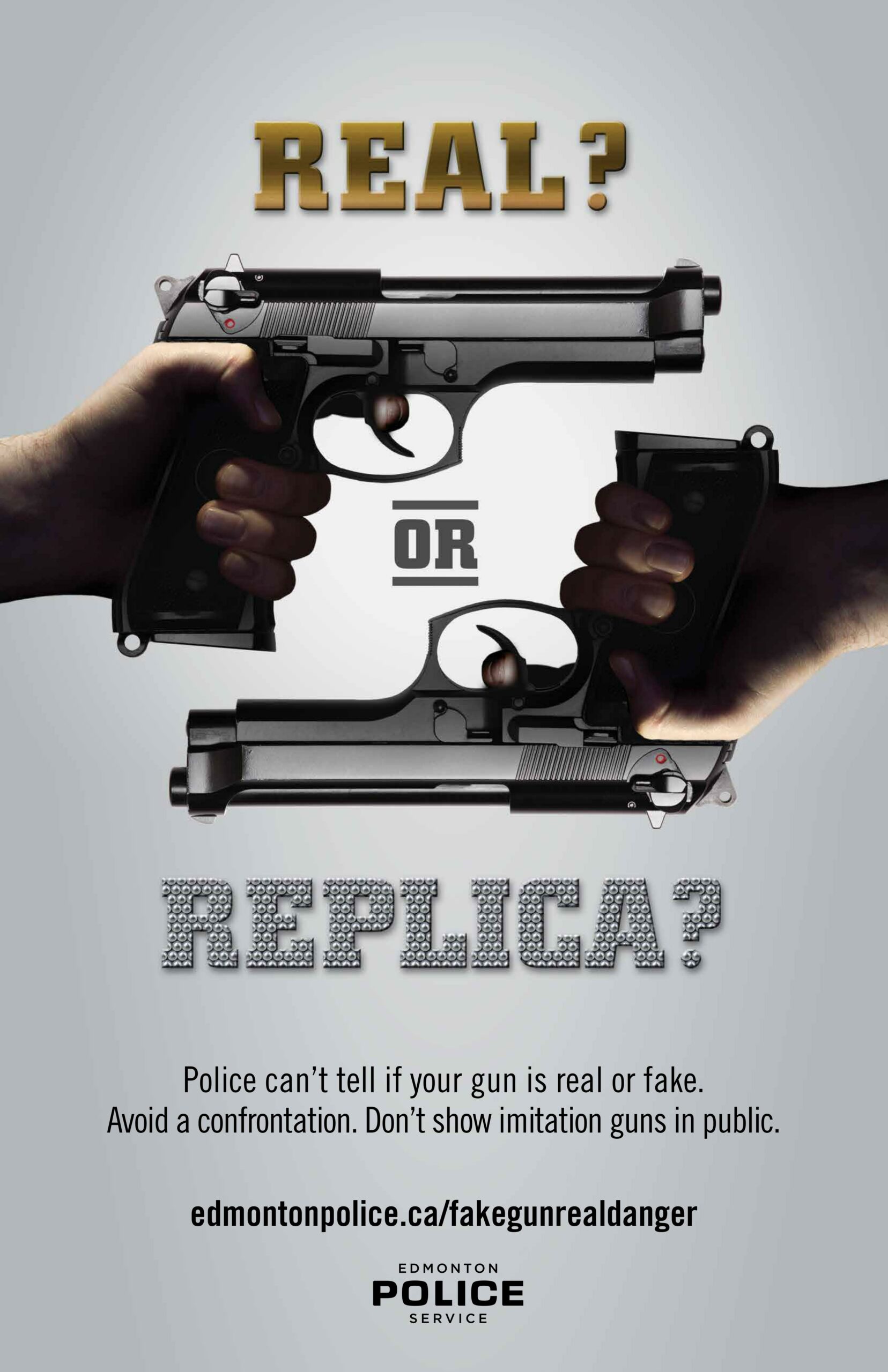

The federal government did not respond to the CACP’s 2000 resolution with new legislation, so several police forces continued to highlight the problem of imitation guns. For example, in 2015, the Edmonton Police Service reported that imitation guns were involved in approximately 1,598 files, and launched a public education campaign in 2016 discouraging people from brandishing replicas.

In 2019, a Manitoba judge urged new rules governing imitation firearms to reduce the risk of fatal shootings involving police and so-called suicides-by-cop. Surveys have found that case law reveals many incidents of imitation firearms used in a variety of crimes, including robbery and sexual assault.

In explaining the expanded ban on replica firearms, Minister for Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Bill Blair said the government had listened to decades of police advocacy on this issue. He said these devices “are often used in crime,” and “present an overwhelming, impossible challenge for law enforcement officers when they are confronted by individuals using these devices. This has, in many circumstances, led to tragic consequences.” Given its long advocacy for action on replica firearms, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police has expressed support for this part of Bill C-21.

If Bill C-21 becomes law with the new replica firearm provisions, where does this leave the airsoft industry? At the very least, it will likely force airsoft businesses to ensure the guns sold do not closely resemble real guns. Blair told the House of Commons that the government has no problem with airsoft guns “except when they are designed and manufactured to exactly replicate dangerous firearms so that they are indistinguishable from those firearms.”

What this means exactly is unclear. How different do airsoft guns have to be from real firearms? Blair has since suggested that manufacturers and retailers could “render them, either by colour or by significant markings, distinguishable from the real thing,” and that, in his view, such changes would not limit the recreational use of airsoft guns.

Will airsoft manufacturers produce products designed specifically for the relatively small Canadian market? Developments in other jurisdictions suggest airsoft will survive despite finally receiving greater legislative supervision. Several nations have identified as a problem the tendency of airsoft to create products that closely resemble real firearms, and have imposed regulations to ensure public safety. For example, the United Kingdom passed legislation affecting airsoft guns. Critics of the British legislation said it would destroy airsoft, but the industry continues.

A Canadian solution needs to allow the games to continue, but ensure that toys look like toys and guns look like guns.