Most Canadians probably don’t know that Canada already has a tax on gas-guzzling vehicles. This isn’t surprising when you realize that the current tax applies only to luxury vehicles such as the Lamborghini Aventador Roadster, retailing for well over $400,000. Buyers of that Lamborghini pay a meagre $4,000 in tax for a whopping 461 grams of CO2 per kilometre (a Honda Civic emits only 158 grams). Survey data show time and time again that Canadians are prepared to do their share to address climate change, but when it comes to the cars and trucks they buy, the tax system does not provide a clear price signal: an incentive to do — or buy — the right thing.

In its current form, the federal excise tax on fuel-inefficient vehicles that was introduced in 2007 under the Conservative government should not be considered an environmental measure. It has no impact on vehicle purchase decisions, which means that it has no impact on GHG emissions or air-polluting emissions.

Some may argue that the tax is no longer needed anyway, now that carbon pricing is being introduced across Canada. But a $30/tonne carbon price (as in British Columbia) implies an additional cost of only about 7 cents per litre of gasoline, representing around 5 percent of the cost at the pump. While that level of price may help change driving behaviour, such as distance travelled, research shows that carbon prices in that range, including the new federal carbon pricing mechanism, are unlikely to significantly influence vehicle purchasing decisions for most buyers, particularly given that gasoline and diesel taxes in Canada are among the lowest across OECD countries. There is a serious policy gap in our “polluter pays” approach in Canada: what matters most to consumers is the ticket price, so vehicle prices should reflect the cost of pollution.

Canadians are in fact purchasing more high-emissions vehicles than ever before. Three of the top five best-selling vehicles in Canada are pickup trucks, and 60 percent of the top 30 vehicles sold in Canada are pickup trucks, SUVs or vans, all heavier polluters than regular cars. These preferences are showing up in Canada’s emissions trends, with these vehicles contributing to a growing proportion of the problem. We must reverse this trend if we are to reduce GHG emissions from personal transportation in Canada.

In past years there was little difference in emissions profiles across pickup trucks, so imposing a gas-guzzler tax on them would have been seen as unfairly penalizing people who needed pickups for their work. Now there is enough variation in emissions across models in every vehicle class that consumers can make more environment-friendly choices and still have the wheels they want. Emissions ratings published by Natural Resources Canada, which rank vehicles from best (10) to worst (1) based on the pollution they emit, range from a low of 2 out of 10 to a high of 5 for pickup trucks. Electric and plug-in hybrid pickup trucks are also emerging on the market, indicating that the future will include options with better emissions ratings, even for those popular vehicles. The range of options is even broader for car and SUV models.

Ontario had a “feebate” program in place between 2000 and 2011 that taxed inefficient vehicles and gave a rebate to owners of efficient vehicles. Analysis of the program showed that it had a significant effect on the mix of passenger vehicles on the road, despite relatively modest fees per vehicle. Chile’s more recent approach takes into consideration both the emissions performance of the vehicle and the retail price, charging more for pollution-intensive, expensive vehicles and less for cleaner, cheaper vehicles. This type of tax provides an incentive to purchase cleaner vehicles, without exacerbating income inequality.

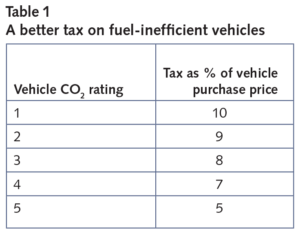

An analysis conducted by Rachel Samson and Sara Rose-Carswell for Équiterre shows that Canada could adopt the best elements of vehicle taxes levied elsewhere in the world and reform its excise tax for fuel-inefficient vehicles to be more environmentally effective, while still providing consumer choice. In order to make low-emissions vehicles more attractive to consumers, the tax should be applied to all vehicles below a certain pollution rating threshold (table 1).

We propose applying the tax to all cars and SUVs that receive a CO2 rating below 6 out of 10, and to all minivans and pickup trucks that receive a CO2 rating below 5. To take into consideration affordability, we suggest a tax that is a percentage of the vehicle purchase price rather than the current lump sum. This would mean that a Ford F150 FFV with a 3.5L engine would cost roughly an additional $1,800 on a $26,000 base price. A GMC Yukon Denali 4WD would cost an additional $5,300 on a $66,000 base price. Popular vehicles such as the Toyota Corolla or Chevrolet Cruze would face no additional tax because their emissions ratings fall above the threshold.

Some argue that taxes on new vehicles actually encourage people to hold on to their older, higher-pollution vehicles longer, defeating the purpose of a tax aimed at decreasing CO2 in the atmosphere. Careful design can easily address this concern. The government could waive all or a portion of the tax on a new vehicle if the purchaser trades-in an older, higher-emitting vehicle (for example, providing a 25 percent discount on the tax for purchasing a vehicle that has a CO2 rating one level higher, up to a 100 percent discount for purchasing a vehicle that is four levels higher).

Reforming the current tax to truly reflect the environmental cost of buying gas guzzlers would encourage Canadians to buy cleaner vehicles, and would therefore result in greater reductions of greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants. When combined with carbon prices, clean fuel standards, and investment in electric-vehicle-charging infrastructure, an effective vehicle tax would help accelerate the transition to the low-carbon and innovative transportation system that Canada needs to meet our greenhouse gas reduction targets.

What’s more, this fiscal reform is needed to put more zero-emissions vehicles on the road in Canada, as the government has committed to do under the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. Transport Minister Marc Garneau and Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Navdeep Bains are developing a pan-Canadian zero-emissions vehicle strategy for 2018. A major barrier to electrification of transport in Canada is the retail price gap between electric vehicles and internal-combustion-engine vehicles. For too long, gasoline and diesel vehicles in Canada have remained artificially cheap: a market failure has allowed buyers to avoid paying the pollution costs of these vehicles. It is time for Canadians to have an accurate price signal and all the environmental information they need to inform their next vehicle purchase.

Photo: Shutterstock/Eduard Goricev

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.