Watching the images from the truck-clogged, diesel-fogged, anarchic streets of downtown Ottawa, it’s easy to forget what looms in the background. The Parliament Buildings, the seat of the federal government and where the prime minister spends a great deal of his time, are what lured the so-called “Freedom Convoy.” Never mind that Centre Block is under construction for the next decade or so, or that many MPs are attending virtually, the symbolism of the place is what counts.

But more than three weeks into the occupation, the convoy’s hard core has managed to violate the (imperfect) social contract that Canadians have long had with this space – that it be an open, shared area for democratic expression. When the fumes subside and the dust settles, we must be vigilant about re-establishing a relationship with Parliament Hill – or better yet, reimagining a better one.

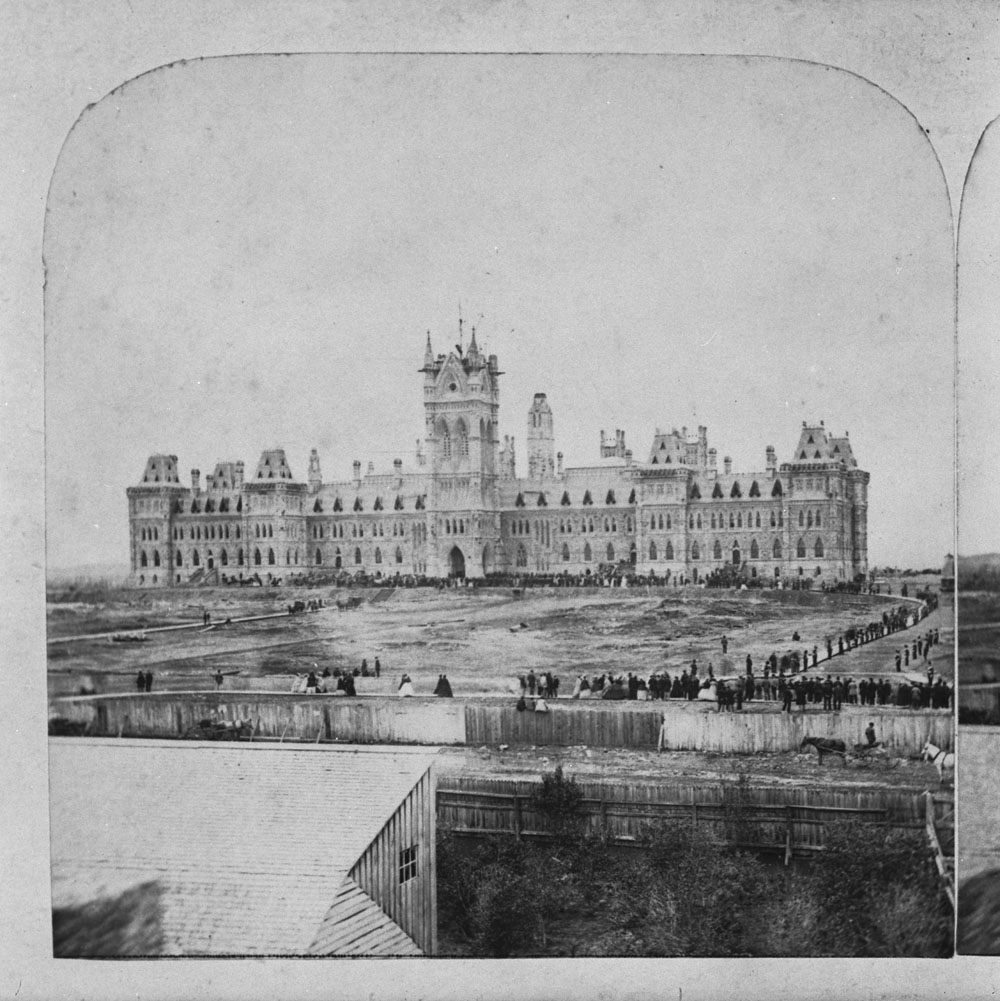

It’s worth noting that when the Parliament Buildings officially opened in June 1866 it wasn’t to a genteel, Victorian-style celebration. The area was a war zone, swarming with soldiers and local militias, as Canada had been under attack that same month by Fenian raiders from the U.S. The Governor General did not receive the typical salute as he opened the last session of the Province of Canada (which predated the Dominion), as all the guns had been sent to the fight.

Despite this rough beginning, the buildings and grand lawn in front of it, have remained one of the most open and welcoming democratic sites in the world. It is not unusual to cross paths with a Member of Parliament, senator or minister on the street. Last year, while sitting in traffic at Wellington and O’Connor, the prime minister and his entourage strode in front of my car – “Hey kids, there’s the prime minister,” I muttered to the backseat.

There’s public Wednesday yoga on the lawn, the changing of the guard for the tourists in the summer, the lighting of the holiday lights in December and the Canada Day celebrations. I recall one winter evening in 2002, when residents spontaneously ran up to the Hill for a celebration of Team Canada’s gold-medal win in men’s Olympic hockey. Some residents have memories of witnessing the repatriation of the Constitution 40 years ago – or even the jubilation of VE-Day as people flooded into downtown.

And yes, Parliament Hill is for protests and demonstrations of all kinds. From the anti-abortion “March for Life,” to the honouring of the children buried in unmarked graves on the grounds of former residential schools. The convoy’s trucks cannot gain access to the lawn area directly around the Parliament Buildings, but their positioning on Wellington and adjacent streets has blocked a national gathering place for nearly three weeks. The intransigence of the protesters spurred the federal government to invoke the Emergencies Act on Monday.

We take the openness of Parliament Hill for granted. Different national and international events have resulted in a throttling of the flow around the precinct. After the 9/11 attacks, the movement of vehicles was restricted and police checkpoints introduced. Circulation inside the building was altered. The 2014 attack on Centre Block by a lone gunman spurred the creation of the Parliamentary Protective Service, and an amplification of police presence.

Changes related to public safety and national security can of course be justified, but they require independent and transparent scrutiny.

The conversations about what Parliament Hill will look like when the renovations are done are largely made behind closed doors with only cursory public input. Many design decisions are being made as the project unfolds. In an unpublicized 2020 report, a group of architects advising the National Capital Commission on the renovations expressed serious concerns that the latest plans for a central visitors’ entrance at the base of the stairs near the Peace Tower would seriously hinder the space that is set aside for gatherings and demonstrations – visitors lining up could find themselves in the middle of a demonstration.

Policing considerations always loom large in these deliberations, and we should wonder whether the convoy occupation will empower the voices that want a more locked down Parliament Hill. If you don’t think it could happen, consider Australia, which blocked off most of the front lawn of its legislature after 9/11, apart from a small, designated area for protest. Whether Canadian police forces and intelligence officials are equipped to deal with the highly organized, foreign-funded actions we are seeing play out is a critical – yet different – conversation.

“Let’s just say that we are observing, learning from every situation that is occurring, and adapting in terms of plans, which will be discussed in camera, in relation to security,” Deputy House of Commons Clerk Michel Patrice told MPs earlier this month at the procedure and House affairs committee.

The convoy occupiers have not only disrupted the lives of residents, but also the space that is supposed to be enjoyed and used by all Canadians. Once they have gone, we should consider what we want from it and how we will protect it. One long overdue reflection is how we honour the Algonquin Anishinaabeg territory on which Parliament Hill is located. Not one centimetre of Ottawa was ever ceded by the Algonquins – in fact, the Crown had promised not to settle these lands in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and then at the Treaty of Niagara in 1764. Algonquin chiefs recently underlined that the convoy actions taking place on their territory were “unacceptable.”

The impact of the protest on the Hill might not be clear until a decade from now, when the construction project is expected to be completed. Until then, let’s not forget to check in with what’s happening behind the construction scaffolds.