“I wonder what those women would be doing now,” says Ruth Eden, assistant deputy minister of infrastructure in the Government of Manitoba. Thirty years ago, Eden was a fresh engineering graduate when the news broke that 14 women had been slain in a horrific act of misogyny at École Polytechnique in Montreal. Her question hangs in the air – it’s painful to consider the lives cut short, so many bright futures extinguished. Twelve of the 14 were engineering students.

In her 1999 essay about the massacre and the public response, media scholar Wendy Hui Kyong Chun – an engineering student at the time of the attack – argues that while we can never fully make sense of what happened that day, every woman scarred by the event can come to the table as a listener. “The important task in listening, then, is to feel the victim’s victories, defeats and silences, know them from within, while at the same time acknowledging that one is not the victim, so that the victim can testify, so that the truth can be reached together.”

It’s in that spirit that I approach this anniversary. Our own response to this tragedy must be founded on a remembrance of its terrible specificity. Our speech must take its root in listening.

One way of doing that is by holding vigils, as engineering schools across the country are doing today. Here at Policy Options, we’ve chosen to share the reflections of four women from across Canada who were students or recent graduates of engineering at the time of the murders. They express grief and a sense of solidarity with their late peers. And they emphasize that while the tragedy marked their lives, it does not define what it means to be a woman in engineering in this country.

Kathryn Woodcock, professor at the Ryerson University School of Occupational and Public Health; director of the THRILL Laboratory at Ryerson.

How did the Dec. 6th Polytechnique massacre impact you at the time?

I was a hospital vice president (Centenary Hospital, in Scarborough, Ont.). I had completed my U Waterloo MASc in 1988 while in that position, but PhD programs demanded a singular focus. So I had just given notice to leave my position after eight years and return to school for a PhD in Engineering beginning in January 1990.

This man — he would have shot me, too, simply for doing what I was meant to do. Because he didn’t want me to do it. Because he felt entitled to be an engineer, and blamed his failure on women instead of himself.

It did not just impact me at the time. I am literally in a café crying today because I was reminded. I wear a button that reads “14, not forgotten” every December 1 to 6.

Did it change how you felt about your career and your place as a woman in it?

As of the date of the event, I was already a professional engineer, and preparing to start a PhD, so I was pretty committed. But it shook me to my core that someone could hate me to the degree of being prepared to shoot me to death — on purpose for a specific reason — without knowing me. Being also deaf, I was pretty accustomed to proving myself, but it was chilling to think that there were still people to whom there was no proving, who would still take the oppression of an entire group to the point of violence, on principle.

Looking back to my first University of Waterloo work term, there were engineering co-op job postings that were understood to be off limits to female students, but that was ancient history, and like most people, I had thought we had moved beyond that by 1989. All at once, it was obvious we had not.

How has your professional life unfolded since obtaining your engineering degree?

Since completing the PhD, I’ve pursued an academic career and work extensively with the global attractions industry on human factors applications to amusement attractions, consulting and delivering training, and just secured my first US patent. Although not in the Faculty of Engineering, I do considerable extracurricular teaching and mentoring of engineering students here and from many universities. I produce and direct a university student competition sponsored by Universal Creative, the design division of Universal Parks & Resorts.

Ruth Eden, assistant deputy minister, Manitoba Infrastructure

How did the Dec. 6th Polytechnique massacre impact you at the time?

Disbelief, I think, would be a good word… But for me, I think what resonates more is just the realization that that event has actually stayed with me for my whole career. It’s always been in the back of my mind that something like that could happen and did happen. And just to be vigilant, I think, for that type of attitude throughout your whole career.

I was a recent grad. I was working at the time. I can’t remember exactly where I was when it happened, but I remember the feeling when I first found out. Just the feeling of… I think almost disbelief, almost panic. And then such a strong sense of sadness that we were living in an age where that could happen. And did happen.

Just to give you a bit of background, I was the first – and I hate the term – female engineer hired by the province of Manitoba. And that was in the fall of 1988. I was working in construction. I was a construction engineer, and it was the first time a woman had ever done that. So, there were no other female engineers around at that point.

But the incident affected my male counterparts – I don’t want to say as much as me – but they were as impacted as I was. It caught everybody… shocked, surprised, to that degree.

Did it change how you felt about your career and your place as a woman in it?

No, because I did have a very supportive work environment. And there were a few individuals who I can give a lot of credit to for that. One of them actually was a Jewish man who was in hiding during World War II and escaped the Nazis. So, when you put that in perspective, what he had to go through… he had had that real-life experience, and he helped me navigate through it for sure.

But I don’t want everyone to just think of the doom and gloom. I made the choice to stay in engineering, even when that was going on, because I loved what I did. I felt like I was a very good engineer, and even though it had happened, it wasn’t going to dissuade me or convince me not to do what I knew in my heart was the right thing.

How has your professional life unfolded since obtaining your engineering degree?

Like I said, I’m very, very lucky to have the work family I did, and the support and the mentors that I did. They looked at everybody as individuals and not based on their gender.

I talked about being the first woman engineer in the province, the first woman construction engineer in the province. I went back and got my master’s while continuing to work. And I’ve just risen through the ranks through my career. At this point I’m assistant deputy minister with Manitoba Infrastructure.

I love what I do, and I wouldn’t change it for anything. I work with great people, and every day in this job I see the value of what we do for the people of Manitoba. And that’s a huge reason why the career that I’ve had, and that I will have, has been so fulfilling. I feel like I’m making a difference for the people of Manitoba every single day.

For all the women thinking about going into engineering, I want them to see that it’s so rewarding. It makes you such a better person, I think, this career. And I don’t want them not to consider it or to be dissuaded by the guidance counsellors or the influencers, the people along the way, who would maybe steer them away.

I’m also past president of our engineering association in Manitoba. And Manitoba is taking a lead role in the 30 by 30 initiative across Canada. It’s an initiative that recognizes that there has to be more women engineers. If we’re trying to find solutions to problems, we should be including all of the great minds across our society, and not just one portion of it. We need our profession to reflect that diversity so that the solutions that we develop are actually representative of society as a whole.

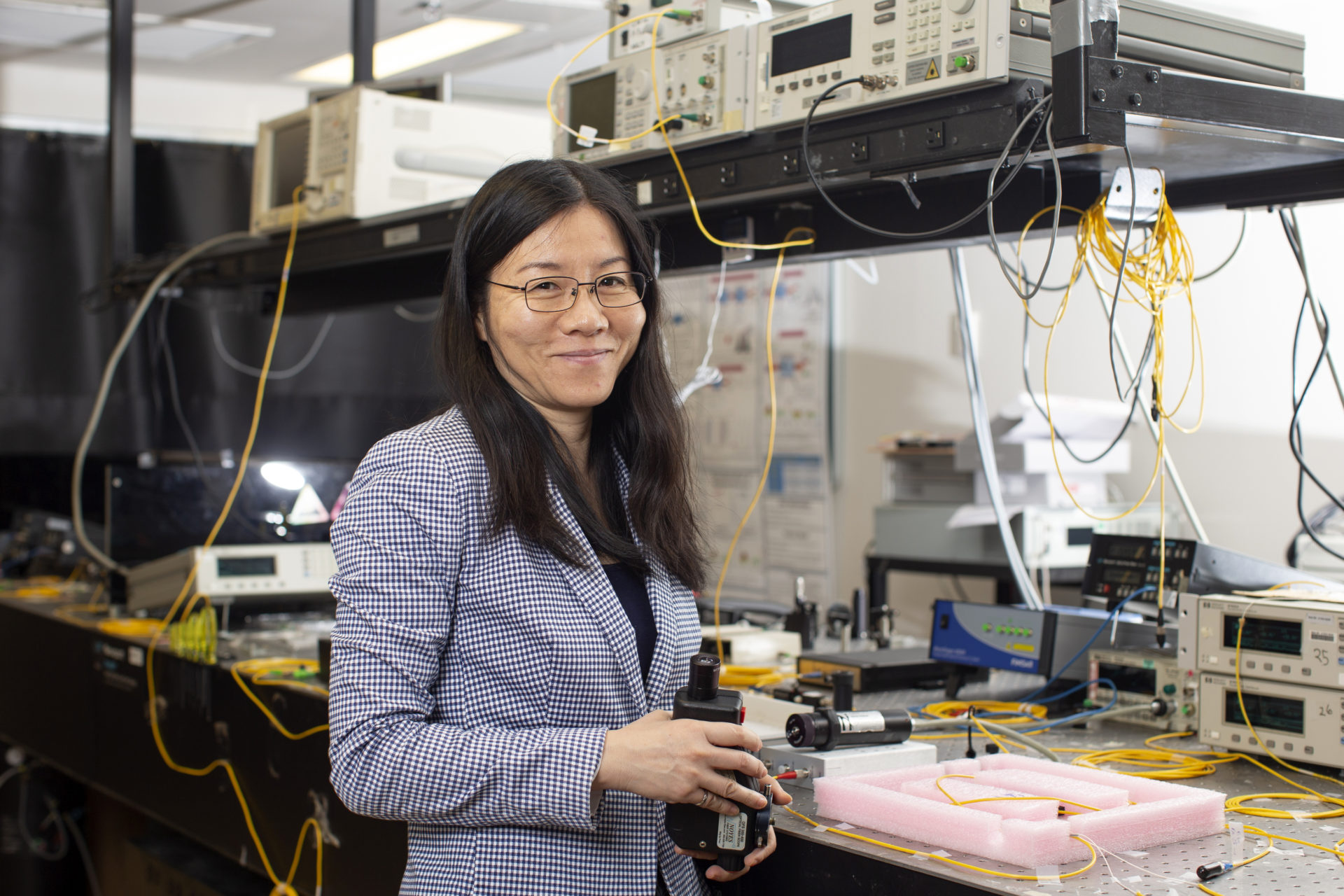

Li Qian, professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (Photonics Group), University of Toronto

How did the Dec. 6th Polytechnique massacre impact you at the time?

I was in Canada studying engineering at the time this tragedy happened. I arrived in Canada only a few months earlier, in September 1989, to start my undergraduate studies in engineering at Memorial University of Newfoundland (MUN). I was 18. It was my first time abroad. Before coming to Canada, I was a physics undergrad in Shanghai and had never been outside China, nor had I heard much about the world outside due to the strict media censorship there.

It was also a tumultuous year for me even before the École Polytechnique tragedy — The Tiananmen massacre took place in June while I was still in China, and I was among the thousands of university students participating in the pro-democracy protests in Shanghai. (There were many pro-democracy protests in various large cities in China at the time, not only in Beijing.)

It was a shock to hear the news on the radio. I couldn’t comprehend it. It was not something I expected to happen in Canada, though I knew very little of Canada at the time. I am not sure if I can comprehend it now. Whatever the social background against which it happened, and whatever unfortunate circumstances that led Lépine to commit this unthinkable crime, I felt, and still feel, it was an isolated incident, not representative of the Canadian society or the Canadian values which I now regard as my own.

Did it change how you felt about your career and your place as a woman in it?

No, not at all. I have always liked to be in STEM, and cannot imagine myself otherwise. No external event, however shocking, is likely to change that. Also, I don’t really think of myself as a “woman in STEM”— I am just my thinking self, and my gender is irrelevant in the profession I choose.

How has your professional life unfolded since obtaining your engineering degree?

I suppose you can say that it unfolded very well. I continued to pursue graduate degrees, and eventually obtained a PhD in electrical engineering (photonics) from U of T. After working in industry for a couple of years, I returned to U of T as a professor. Engineering was not my passion at 18 — physics was. I took engineering because it was the only way I could pay for my education in Canada on my own, thanks to the co-op program at MUN. But over the years I came to like, even be passionate about, the engineering profession.

Lianna Mah, vice president of business development at Associated Engineering in Vancouver

How did the Dec. 6th Polytechnique massacre impact you at the time?

In 1989, I was an engineer-in-training with a consulting firm in London, Ont. I had recently graduated from UBC with an undergraduate degree in civil engineering and a master’s degree in environmental engineering.

I had grown up in an environment where my parents encouraged me to be anything I wanted to be. While there were few women in engineering at UBC when I was completing my degrees, and there was only one other female engineer at my workplace, I did not feel that being a woman was a barrier to my career. That changed on December 6, 1989.

I heard about the massacre while I was at work. I recall feeling extremely sad and angry at the same time. I was outraged that these young women were murdered because of their gender, and that their lives were cut short because they had chosen to study engineering.

Did it change how you felt about your career and your place as a woman in it?

While I had seldom felt isolation as an engineering student or an engineer-in-training, at that moment I felt an extreme sense of isolation. There was no one in the office with whom I could share and express my feelings of grief and outrage about the murders, and loneliness that there were not more women in our profession. I had no female role models or mentors who I could go to for advice.

The massacre of these women became a catalyst for me to find and connect with other women engineers and to do more to promote women in engineering. That’s when I started to get more involved, and with a group of women we formed the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of BC’s Division for the Advancement of Women in Engineering and Geoscience (now Engineers & Geoscientists of BC’s Women in Engineering and Geoscience Division).

DAWEG established a mentoring program and school visits, created a regular newsletter, and organized conferences and networking events to promote and advocate for women in engineering and geoscience. I believe our work helped to provide awareness and encourage girls to pursue a career in engineering, and create a network for women in engineering which improved retention of women in our profession.

How has your professional life unfolded since obtaining your engineering degree?

Throughout my career I have worked for companies that are open to diversity. My supervisors and managers gave me the opportunity to work on a wide variety of projects and to take on a range of challenges.

I have participated in the design of water and wastewater treatment facilities, and water supply and wastewater collection systems in British Columbia and Ontario. I also had the opportunity to work on a waste management project in the British Virgin Islands and travelled there twice as part of the project.

One of the highlights of my career was working on the design of upgrades to the Annacis Island and Lulu Island Wastewater Treatment Plants for Metro Vancouver in the 1990s. The upgrades improved the quality of wastewater treated at these two facilities, which together treat wastewater from over 1 million people in Metro Vancouver. As an environmental engineer, this was a project of a lifetime, in particular to work with leading professionals in the Lower Mainland, and from across Canada and the US.

For the past 15 years, I have been responsible for business development, marketing and communications at Associated Engineering. I’m also corporate champion for our Women in Science and Engineering Retention (WISER) Committee and Young Professionals Group…

While my career experiences have been largely positive, I know that women still feel isolated in the workplace; some women are harassed on job sites; and some women are not hired or promoted because they are women. While we have done so much to welcome women to our profession, we still have much work to do to improve the culture for women in engineering in our profession.

We need to continue the conversation about the importance of diversity and inclusion. A diverse and inclusive workplace that includes people with a wide range of backgrounds, skills and experience spurs creativity and results in better outcomes and stronger organizations.

Photo: Fourteen lights shine skyward at a Montreal vigil on December 6, 2018 honouring the victims of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Ryan Remiorz

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.