(Version française disponible ici)

In its most recent budget, the Trudeau government announced plans to launch a year-long review of federally funded skills-training programs to see if improvements can be made. The changes can’t come soon enough.

Policy experts have been warning for some time that current training offerings aren’t meeting the needs of workers. In workshops held by the Institute for Research on Public Policy, we heard widespread support from employer groups, union representatives, and policy experts for better-designed and more-effective training programs to help workers withstand and adapt to labour market disruptions.

For example, Toronto-based Ada Support Inc. recently released software that allows companies to use generative AI rather than live agents to answer most customer-service inquiries. AI technologies aren’t the only source of turmoil on the horizon. Remote work could lead to greater international competition for service-sector jobs, much like globalization did with the manufacturing sector two decades ago. As well, the shift to net-zero carbon emissions is expected to do away with many existing jobs in fossil-fuel industries and create new ones in the clean-energy sector. The sustainable jobs plan, the federal government’s strategy to transition workers away from fossil-fuel industries, acknowledges that some new jobs won’t require new skills or significant retraining. But in other areas, training programs and financial supports will be key for workers seeking to adapt.

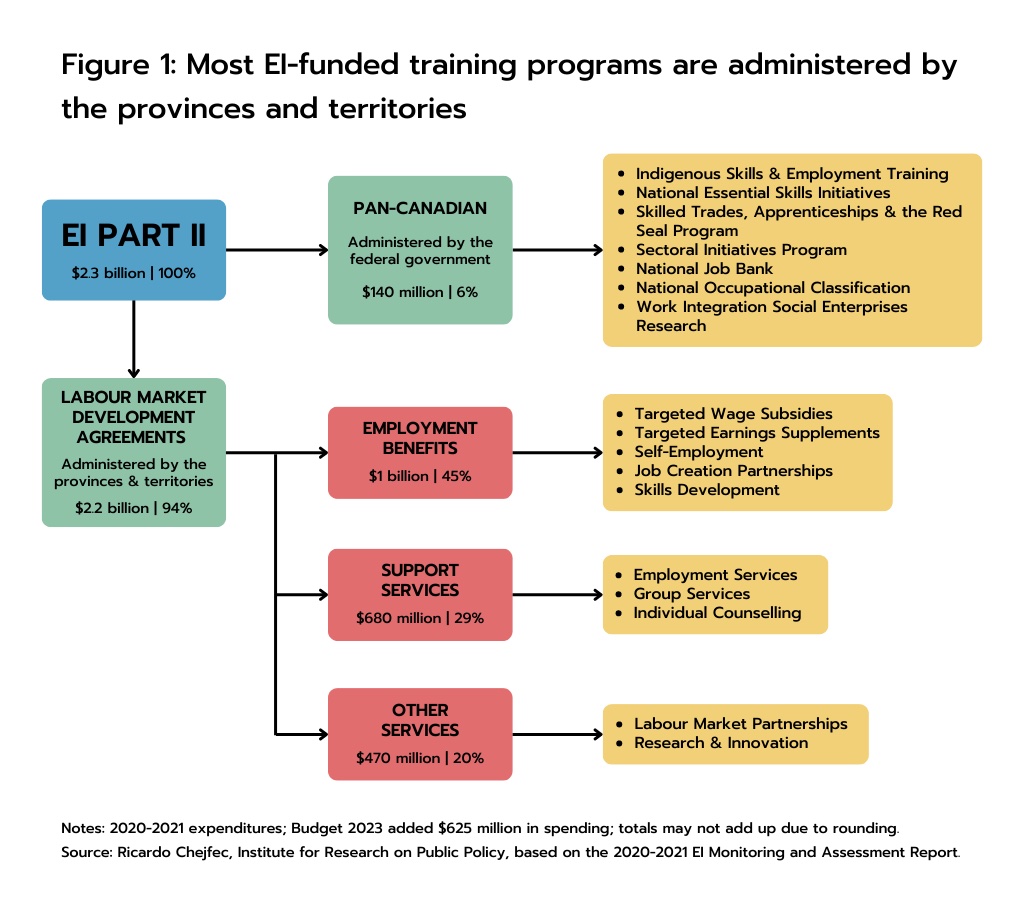

The federal government spends almost $3 billion a year on training programs, and the 2023 budget set aside an additional $625 million for that in this fiscal year. Much of this money flows through the employment insurance program (under part two of the EI Act) and is used to fund training initiatives provided either directly by the federal government or through transfers to the provinces and territories. The money goes toward skills training, wage subsidies, career counselling and help with resumé preparation, among other things.

Despite a series of investments in recent federal budgets, the current package of training programs lacks a coherent framework (figure 1).

Uptake for many of these programs is low, funding is insufficient, and they don’t adequately target low-income workers and/or those most vulnerable to job loss and precarious work. Under current rules, it’s possible for EI claimants to enrol in a training program for which they pay while they collect EI, but they must be ready to work if they receive a job offer, which can mean abandoning training. Workers who quit their jobs cannot collect EI, even those in low-wage and precarious jobs who quit to enrol in a training course.

How to enhance EI-funded training programs

A recent commentary published by the IRPP proposes a number of initiatives to enhance the training programs funded through EI. For one thing, it recommends expanding the premium reduction program. As currently structured, this program provides businesses that offer short-term disability benefits to their employees a reduction in the EI premiums that they pay. This is meant to encourage more employers to provide short-term disability benefits and reduce dependence on EI. The IRPP commentary suggests extending the premium reduction to small and mid-sized firms that offer training programs for basic skills.

Skills Boost, another EI-funded program, allows claimants who have lost their jobs after several years in the workforce to ask Service Canada for permission to continue receiving EI benefits while taking a full-time training course. But uptake has been tepid: in 2020-21, the most recent year for which figures are available, just 612 claimants received permission, less than one per cent of long-tenured workers who were receiving claims. The commentary proposes broadening the program to include more workers, such as those who have been working for a shorter time and/or who have low skills.

The federal government should also consider expanding the work-sharing program, an initiative that is intended to help employers avoid layoffs during tough times. Under this program, employees who agree to reduce their working hours can collect EI benefits to supplement their wages for up to nine months. They can enrol in a training program while they take part in a work-sharing agreement, but the training must be completed during non-work hours and they can’t receive EI benefits for the time they spend on training. One option is to introduce a revamped program for work-sharing while learning. Briefly in place in the early 2000s, this program permitted workers in industries in high-unemployment regions that were facing structural changes to collect EI benefits for up to a year while attending employer-funded training. The commentary recommends reinstating it but making it available to all workers.

In the IRPP’s roundtable discussions, the working group debated whether to allow employees who quit their jobs to collect EI, something they haven’t been able to do since 1993, when eligibility criteria were tightened and benefits made less generous. Business groups are concerned that permitting this would raise program costs and exacerbate labour shortages. But having access to a skilled pool of workers would be a boon to businesses and the economy. The commentary recommends allowing only those without post-secondary education who quit to enrol in education and training to be eligible. To set a limit on the amount of time spent on training, it suggests giving employees a set number of weeks over their careers, which they could use to pursue several shorter programs or a longer one as they see fit.

Another area ripe for reform is the Canada training benefit, which is separate from programs funded through EI. The program was introduced in 2019 as a means of providing retraining funds directly to workers. One part, the Canada training credit, provides eligible workers an annual tax credit of $250 up to a lifetime limit of $5,000. The funds accumulate in an account administered by the Canada Revenue Agency and can be used to cover up to half the cost of some university and college programs. But Canadians must pay the costs upfront and claim the credit at tax time, which isn’t well-suited to the needs of low-income learners. Neither is it suited to the needs of older workers because it would take 20 years to accumulate the full credit.

The second part, the EI training support benefit, is intended to give workers up to four weeks of benefits while they are enrolled in training to help cover their living expenses. But this provision, though long promised, has yet to come into force.

Meaningful reform will require government co-operation

In the IRPP’s roundtable discussions, we also heard calls for improved personal counselling and career-planning services so Canadians can more easily seek help to identify programs that best suit their needs. In many cases, these already exist but are little-used. The federal government took a step in the right direction in 2019 by making employment assistance services, such as resumé preparation and help with job searches, available to all Canadians rather than just those who are unemployed. There is also a new training section being added to the Job Bank. But more could be done on this front.

Of course, meaningful reform can come only if governments work together. Most of the money for EI-funded training supports flows to the provinces and territories through what are known as labour market development agreements, or LMDAs. While the funds come from the EI account, the programs are designed and delivered by provincial and territorial governments. The two levels of government should work together to identify gaps in the current system and opportunities for greater co-ordination.

The 2022 report by the Auditor General of Canada found that workers who had lost their jobs because of the phase-out of coal-fired power plants were not well-served by the federal government’s “business as usual” approach, which consisted largely of providing them EI benefits. As the labour market evolves and demands a different set of skills, workers will need high-quality training programs as well as income support to make the necessary successful transitions.