All is not quiet on the northern front. Last month, Canada took strategic steps with Finland and Sweden to strengthen defence and security relations in the region. This action – essential to our Arctic leadership and national security – deserves applause.

Now, however, Canada must up its Arctic game westward because much of the Arctic’s action occurs where it meets the North Pacific Ocean.

Five Chinese “research” ships plied the Bering Strait, Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea this summer – the most ever. Off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, the Russian and Chinese navies conducted exercises again this year. In 2024, Russian ships escorted Chinese coast guard vessels into the Arctic for the first time. Joint Russia-China bomber patrols have flown over the Bering Sea. In the Arctic and North Pacific, Russia and China are at their closest in decades.

Commercial developments are also accelerating. After testing a container ship route from Arkhangelsk to Shanghai last year, a Chinese company launched its first sailing on a new seasonal “China-Europe Arctic Express” route to British, German and Dutch ports. Russia is building infrastructure to export more energy and minerals to Asia, primarily China, via this path.

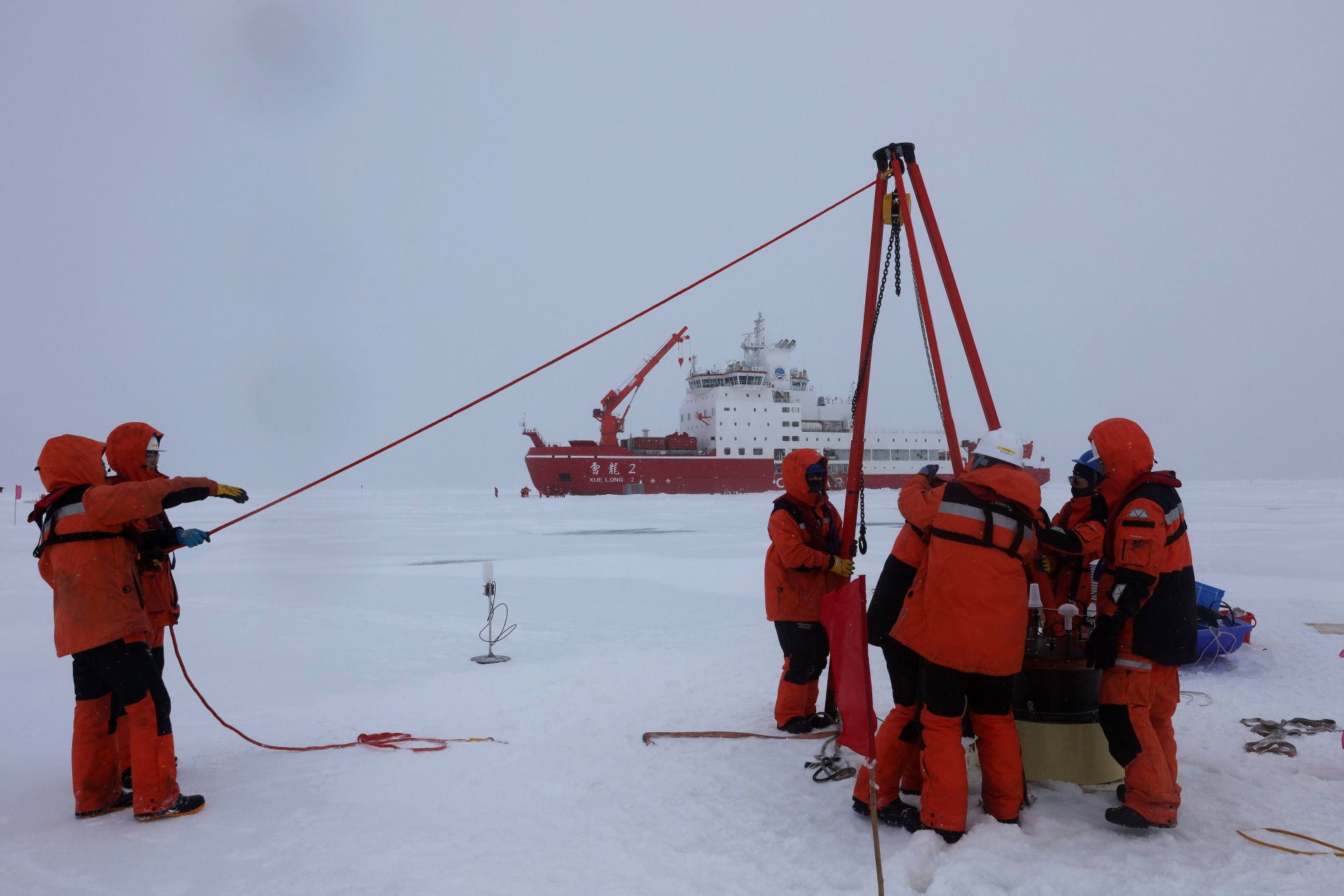

Meanwhile, Canada is participating in Operation Latitude with U.S. forces, training together in the Bering Sea. Although denied by officials, a Canadian Coast Guard ship in July followed one of the Chinese icebreakers as it left Shanghai and headed north. A Royal Canadian Navy frigate kept an eye last year on a northbound Chinese icebreaker, the Xue Long 2. Royal Canadian Air Force patrol aircraft, sometimes operating out of Alaska, have been in the mix.

Canada’s missing strategy

But Canadian policymakers have been slow to grasp how Russia’s Arctic strategy prioritizes the Northern Pacific and how China’s Pacific priorities intersect with its Arctic aspirations.

In its Indo-Pacific strategy, Canada nods to the North Pacific Ocean as part of its neighbourhood. This is the right instinct but the idea never evolved beyond vague rhetoric. Ottawa provided no roadmap, concrete priorities or partnership framework. The concept still holds real promise, but only if Canada grounds it in tangible collaboration.

Canada needs an actionable strategy. South Korea and Japan would be centrepieces and there is good reason to think they would be game. Arctic science, joint shipbuilding and tackling illegal fishing are practical angles that can give the idea credibility and strategic weight.

Tokyo has steadily deepened its Arctic focus as part of its wider free and open Indo-Pacific vision. It’s already investing in Arctic science and technology, as well as being a strong voice advancing rules-based governance through the Arctic Council. Japan’s robust shipbuilding industry and advanced technology in LNG transport, offshore infrastructure and green shipping would make it a natural partner.

Likewise, Seoul has clear incentives to work with Canada. As a global shipbuilding and port development leader, South Korea has the industrial capacity and strategic interest to contribute to Arctic security and sustainable development. Its advanced icebreaking technology, growing interest in northern shipping routes and strong scientific research record in the Arctic position it as an indispensable partner.

A roadmap for trilateral co-operation

Here’s how Canada can lead a vision of Arctic and North Pacific security, resilience and prosperity.

The first step would be the development of an international agenda connecting shipbuilding in the three countries, including options for maritime mobility, accompanied by a working group on future shipping and resource development in the Canadian Arctic.

In addition, technology could address hybrid and grey-zone warfare in the Pacific and Arctic oceans, helping with co-operation on sensor packages and data sharing, as well as more joint efforts against illegal fishing. A trilateral Arctic science pact would be a step in reinforcing evidence-based policy.

Mary Simon: How do Canada and Inuit get to win-win in the Arctic?

All this would signal to China and Russia that Canada sets the tone on sea lanes leading to and through the Arctic. The U.S. would also take note, with Alaska sitting at a trisection of U.S., Chinese and Russian power. Such trilateral co-operation would position Canada (and Japan and South Korea) to create some fear of missing out in Washington. Building on invigorated ties, the three countries could pitch a North Pacific “quad,” if the U.S. wants onboard.

Given the current state of relations with the U.S., Canada should take independent initiatives guided by its own strategic interests – while communicating to Washington at each step how the two countries’ security interests align and how Canadian international engagement will – as a byproduct – make the U.S. safer and more prosperous. In addition, Canada will independently be strengthening its position in two of its oceans at once.