(Version française disponible ici)

The climate crisis is wreaking havoc on our planet. Over thirty years ago, thousands of scientists from around the globe issued a warning: humanity and the natural world were on a collision course. That warning has become our lived reality. Humanity is not merely colliding with nature; we are driving the collapse through a model of economic and legal globalization that treats the Earth as limitless.

Every year, we release more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, temperatures rise to unprecedented levels, and forests burn in every corner of the globe. Nineteen to 23 million tons of plastic enter our oceans yearly, along with 300 to 400 million tons of heavy metals, solvents, and toxic sludge. One million species are currently threatened with extinction. Multiple ecological tipping points may soon be crossed, with profound and irreversible consequences.

Despite the magnitude of the crisis, the efforts of the international community remain insufficient. One of the key issues is that negotiations take time. In 2016, for instance, the Paris Agreement finally came into force, setting a global target to keep the rise in temperature below two degrees Celsius. That instrument, however, only came to fruition after years of painful negotiation. More recently, the High Seas Treaty was adopted to protect biodiversity in the high seas, but only after several years of negotiations. If history is any guide, any new treaties we need to address outstanding environmental issues will similarly take years to negotiate.

A point of no return

We simply do not have that time. Humanity has reached a point of no return and can no longer afford such lengthy negotiations. The decade in which we find ourselves will be decisive, but we lack the tools to respond quickly to the existential challenges we face.

Today’s dominant legal and economic doctrines, forged during the Holocene to drive industrial development and global trade, were not conceived with the complex dynamics of the Anthropocene in mind. They were built for stability and growth in an era of presumed abundance, and as such, often lack the responsiveness needed to engage with ecological thresholds, feedback loops, and planetary boundaries.

New conditions call for new solutions. It is time to reconsider the way we resolve environmental disputes and negotiate agreements more efficiently. To do so, we need new mechanisms that will truly foster collaboration and cooperation on the global stage. This is where environmental mediation comes in.

Mediation: an underutilized tool

Mediation is a staple of many justice systems worldwide. At its core, it involves negotiations between parties to resolve a dispute or reach an agreement, but with the assistance of a neutral, impartial, and independent third party. Mediators who play this role are trained to identify the interests that lie behind the parties’ positions and to unpack their disagreements in a way that is often more efficient than direct negotiation.

The skills – and sometimes even the art – that these mediators bring to the table have the potential to reshape the negotiation of environmental disputes and treaties. That idea is not entirely new. Mediation is already used to resolve environmental conflicts in various domestic contexts. In a 2015 guide, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) illustrated how mediation helped solve complex environmental disputes on different continents.

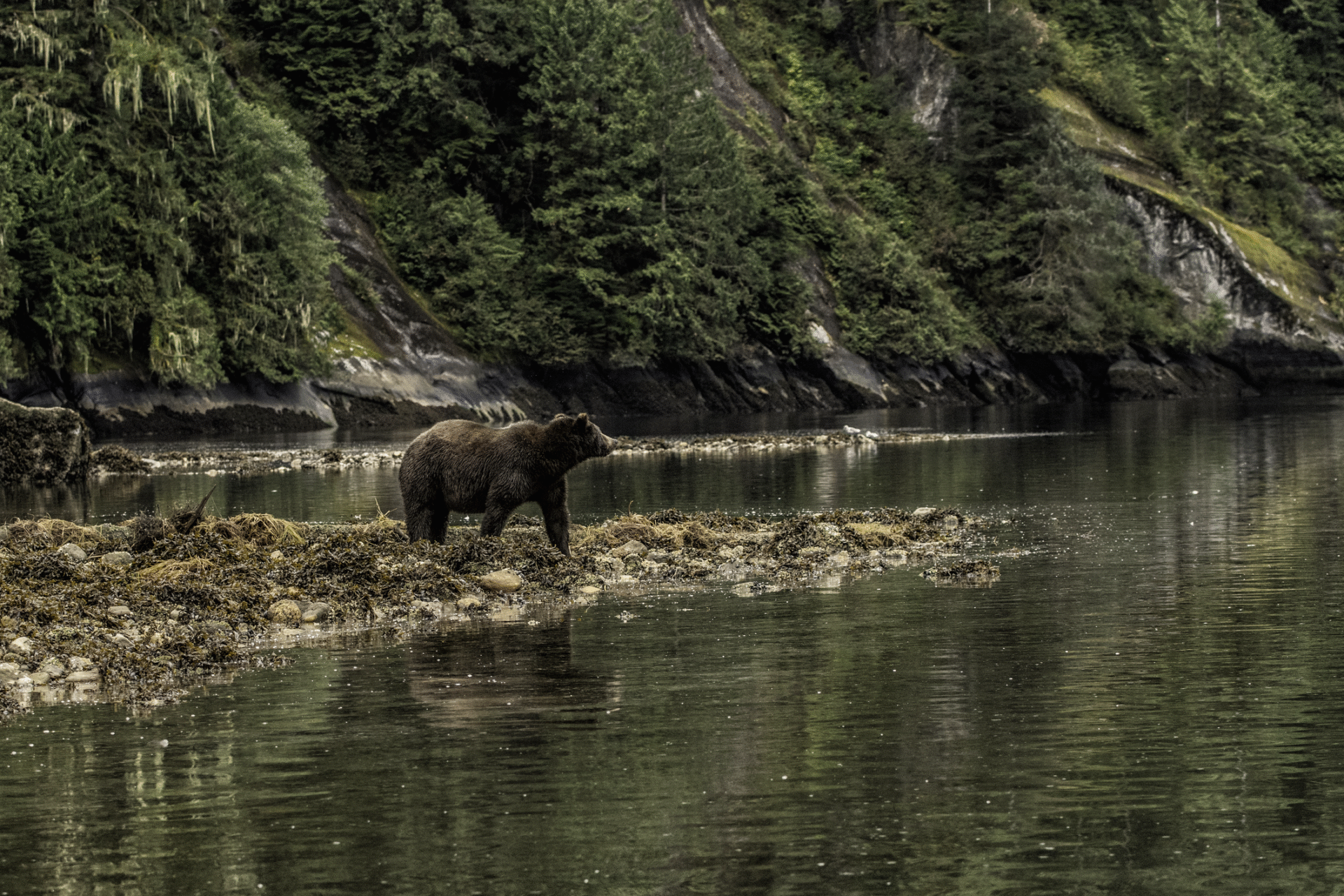

In Canada, mediation helped resolve a conflict among the forestry industry, environmental groups and First Nations over logging in British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest. Through dialogue, the parties reached an unprecedented agreement that protects 85 per cent of the forest while providing a framework for sustainable logging.

Yet, despite its successes, the power of mediation remains largely untapped on the international stage. While that context differs from domestic ones, both politically and in the legal instruments that may apply, mediation holds the same potential. As the UNEP itself noted more than ten years ago, “Mediation has been underutilized by the international system in addressing disputes over natural resources … the international system still lags behind in identifying or acting on opportunities for proactive use of mediation as a tool.”

It is now time to bridge that gap and involve expert mediators in environmental talks to facilitate a process that has become too cumbersome to deal with the complex and dynamic issues we currently face.

Speed up the process through mediation

What would that mean, concretely? Imagine that two neighbouring countries seek to minimize air and water pollution crossing their borders. Under a more traditional framework, their representatives would engage in direct negotiations, which might quickly become protracted as each party becomes entrenched in their respective positions.

Past experience shows that involving a mediator might speed up the process through four different stages. First, a preliminary phase would involve the parties concluding a mediation protocol through which they would select their mediator, venue and timetable, identify their representatives, and agree on the mediator’s mandate.

With that protocol in place, the second, preparatory phase, would involve the parties and the mediator jointly laying the foundations for the mediation by determining its scope, work plan, and logistics. At that stage, the mediator may also develop a preliminary assessment of the options available.

In most cases, the mediator will meet individually with each party to understand their positions and, often, identify the underlying interests and motivations that may be hidden behind them. These meetings may provide an opportunity to test potential solutions to be developed further during the mediation.

The third phase is the mediation itself. In environmental matters, scientists and experts are often called upon to present technical reports that shed light on areas of disagreement, allowing all stakeholders to work with a common set of information. The negotiation itself can then proceed, guided by the mediator’s expert hand, to resolve each issue and reach an agreement between the parties. Even if no agreement is reached, mediation often allows the parties to circumscribe their disagreement and boil it down to a minimal set of key points. Finally, the fourth stage involves implementing the agreement reached between the parties.

Create a specialized unit

How can that system take shape? Throughout the world, expert mediators are available and ready to contribute their unique skill set to addressing the climate crisis. We propose the creation of a new International Climate Mediation Unit, which could be located within the UNEP or the UN Secretariat, thereby uniting these experts under a single team.

This specialized unit would include field mediators ready to resolve conflicts generated by the climate crisis and its consequences, including the increasingly frequent displacement of populations in the wake of disasters.

It would also include governance mediators prepared to help countries reach climate agreements. And it would include tax mediators working toward the establishment of an international tax system that generates the financial means required to prevent and compensate for environmental harm.

This proposal is an urgent alternative that is not simply a procedural fix, but a call to redesign how we resolve conflict in a world on fire. This call for a new architecture of environmental mediation confronts the institutional paralysis that has long stalled action on what is widely understood today as an existential threat to humanity and all of life.

The only missing piece is the political willingness to shepherd and implement this system. Canada can play a key role in that endeavour. We take pride in our position on the international stage and, in particular, in the role we have played in fostering peace and agreement.

Our government can act now and lead the development of this new solution for addressing the climate crisis. Only then can we begin to weave a shared future, what the Anishinaabe call mamidosewin: walking together toward a common destination.