The past decade has featured both an abysmal Canadian trade performance and an ambitious policy agenda to further liberalize Canadian trade.

For many trade commentators, the way to improve Canada’s poor results on trade is to implement the big outstanding deals — the Comprehensive and Economic Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) — and to launch new talks with other important partners such as China. This is typically thought to improve the performance of Canadian firms by enhancing their market access abroad and increasing the competitive pressures they face at home.

In his new commentary for the IRPP trade volume, Jim Stanford (Harold Innis Industry Professor of Economics at McMaster University and Economic Advisor to Unifor) agrees with many in Canada’s policy community that we have a trade problem, but he offers a different diagnosis of its causes and proposes alternative policy priorities. His work raises an important and provocative question: Is implementing more free trade and investment deals the right way to address Canada’s trade woes, or has this policy focus actually been part of the problem?

Canada’s poor trade performance

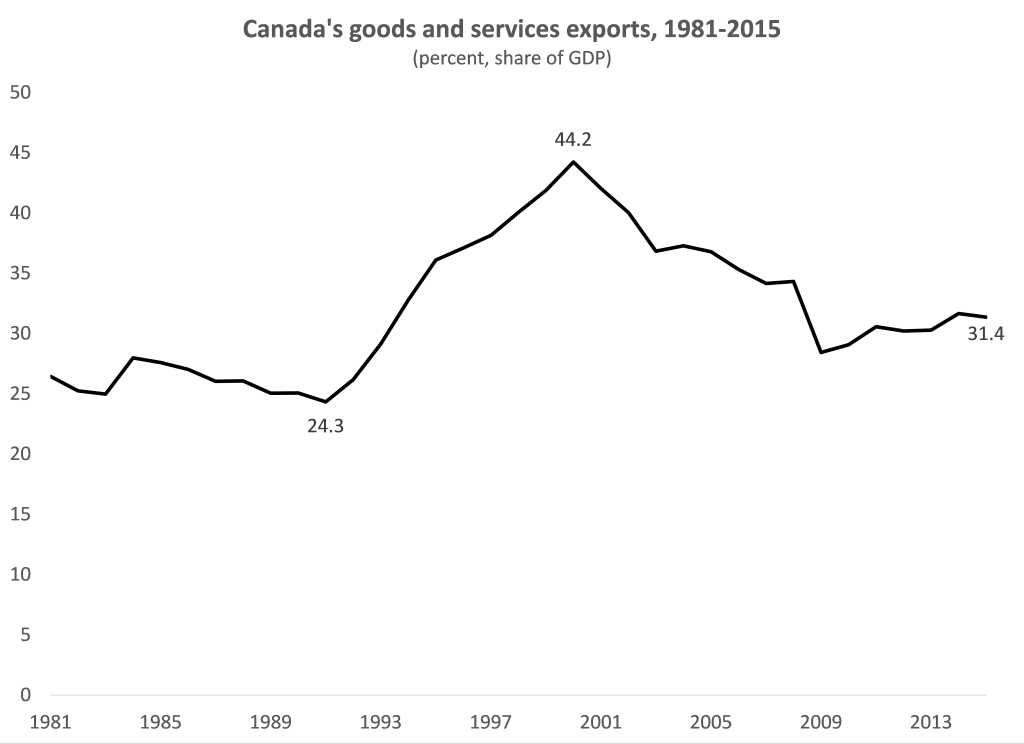

Canada’s trade intensity rose significantly in the 1990s — primarily through adjustments to the new Canada-US free trade deal. However, since 2001 our exports as a share of GDP have given back most of these earlier gains:

Source: Statistics Canada CANSIM Table 380-0064.

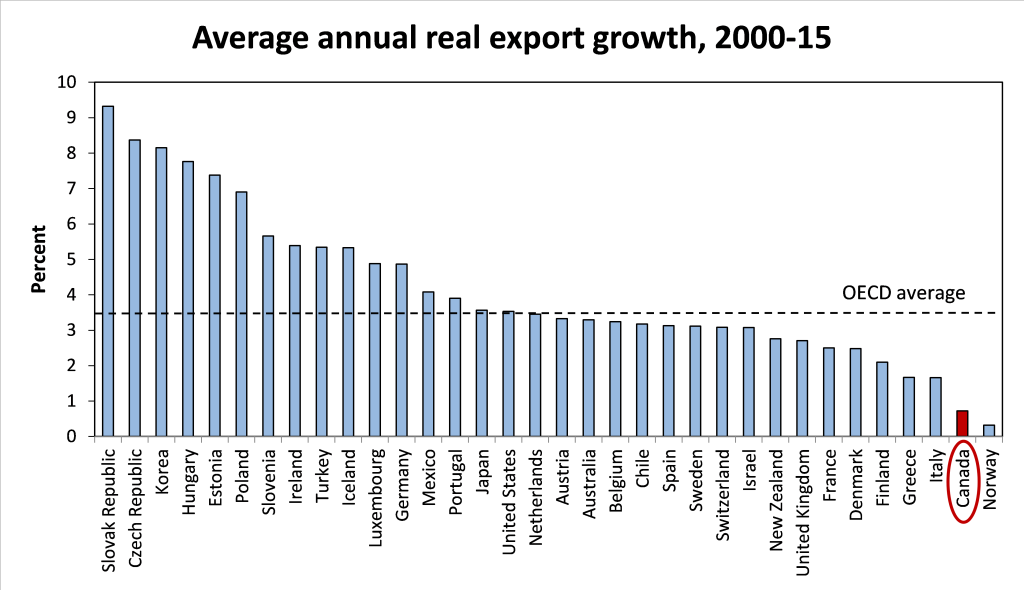

Since the turn of the century, Canada has not only fared poorly relative to its own past performance, but also compared with the OECD, as the growth of our real export volumes ranked a disappointing 33rd out of 34 countries.

Source: Calculations using OECD Economic Outlook 98 database, Annex Table 39

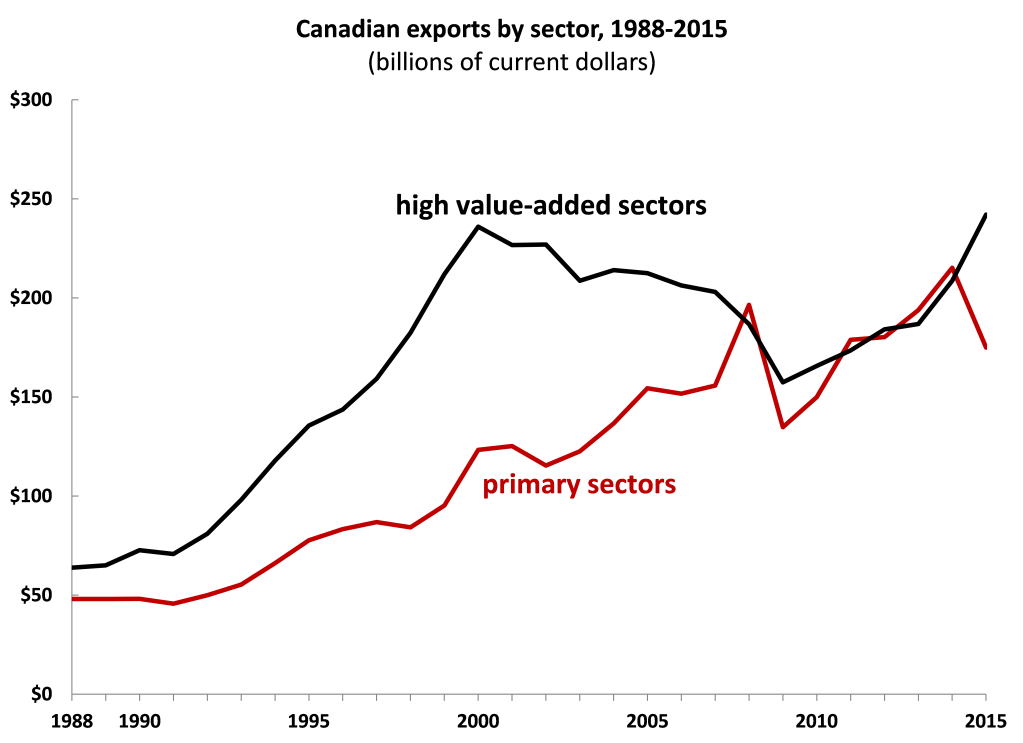

Stanford says that deterioration in the average quality of Canada’s exports is just as troubling as the weakness in the quantity. Our export composition shifted to primary sectors (agriculture, energy, mining and forestry) and away from what he calls “high value-added” sectors (auto, aerospace, industrial machinery and equipment, electronics and consumer products).

Source: Calculations using Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 228-8059.

The shift to exporting more primary goods was encouraged by higher global prices for these commodities, of course, but there’s more to the story. Stanford also partly attributes Canada’s lack of international competitiveness in the high value-added sectors to an over-valued currency (which was associated with the resource boom). He points to underlying structural weaknesses — namely, failing to build a sufficient base of innovative, export-oriented businesses in Canada that sell value-added products and services that world markets demand.

As an example, he points out that Canada has essentially lost its stature as a leading source of knowledge, innovation and productivity as it fell from being ranked as the 6th most technically complex economy in 1980 to 33rd by 2013. Moreover, aside from short-lived capital inflows in the resource sector, Canada hasn’t been a particularly appealing site for foreign direct investment in recent years, either.

Canada’s ambitious trade agenda

Interestingly, the deterioration in Canada’s international trade performance occurred alongside a period of ambitious trade and investment liberalization. Comparing the current state of Canada’s negotiations with just a decade earlier reveals much action. Canada’s trade deals have added countries in South America, and the government is hoping to include many more in Europe and the Pacific Rim:

Source: Stanford 2016

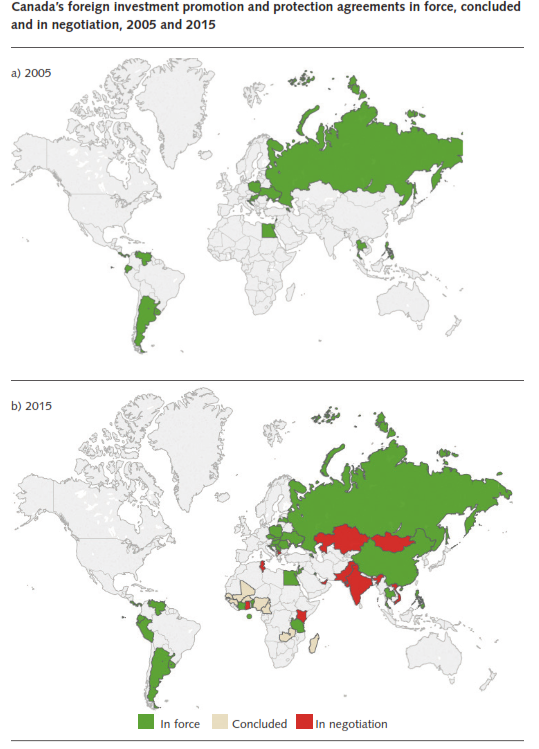

Foreign investment agreements have recently added China as well as several Eastern European and African countries:

Source: Stanford 2016

Time for a new policy focus

But Stanford finds that Canada’s trade flows to free trade agreement partners have performed even worse than our trade with the rest of the world, particularly for manufactured goods. Export growth was slower with FTA partners than with other countries, but import growth was faster. And while the correlation between trade liberalization and poorer trade performance does not prove causation, Stanford’s results and questions raise the bar for trade deal advocates to provide empirical evidence of the practical benefits of recent deals.

Stanford argues that mutual trade and investment liberalization has probably caused more harm than good for Canada in the 21st century, because our economy simply hasn’t been competitive, based on either cost (mostly due to an overvalued currency) or quality/innovation.

Canada’s structurally weak productivity and innovation record means that our firms have been unable to fully capitalize on new opportunities abroad (including those resulting from recent trade and investment deals). Yet those deals have simultaneously exposed Canadian firms to increased foreign competition at home, which can undermine, rather than strengthen, Canada’s productive capacity when our firms are incapable of meeting this challenge.

Stanford therefore suggests that Canada shift its policy focus away from implementing more big trade deals. And even within such debates, he says our attention should shift to concretely and empirically evaluating the impacts of those deals based on the interests of the Canadian economy and Canadian industries (rather than assuming that trade liberalization is always mutually beneficial, as predicted by conventional economic theory).

He says that Canadian policymakers should explore other ways to support the development and growth of globally oriented, innovative, technologically intensive firms in Canada. Policies need to help these firms to upgrade their activities and project themselves more effectively onto the global stage.

To strengthen Canada’s business sector, policy should encourage the growth of Canadian-based firms so that they can become large and outward-looking enough to penetrate global markets. Instead, our current approach often subsidizes small companies with perverse incentives that discourage growth (e.g., lower tax rates for small firms).

At the very least, Stanford says that Canada’s trade policy community should be more open to the possibility that signing more FTAs may not be a magic bullet for Canada’s trade woes. He argues that the effects of such deals can be positive or negative, depending on their provisions, the trading partners involved and the readiness of Canadian industries to grow exports and attract mobile investment.

Stanford judges that over the past decade trade negotiations have probably done more harm than good to Canada’s trade and foreign investment record. Going further down this same road with more blockbuster trade deals might just make things worse, he says. I encourage you to read the full chapter here.

Photo: Volodymyr Kyrylyuk / Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.