In 2016 there were at least 2,458 apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada. A recent upswing in morbidity and mortality linked to this group of effective but highly addictive analgesics has given rise to something of a nationwide moral panic. Terms like harm reduction, methadone and naloxone are now part of our national lexicon. More and more, Canadians are demanding action from political leaders to curtail deaths from opioids. Despite an array of opinions about how to solve what has been called Canada’s biggest public health crisis, headline writers and politicians seem to agree on one thing: it is going to get worse.

The root causes of this crisis are complex: physicians’ prescribing patterns, slow uptake of harm reduction strategies by policy-makers, an embarrassing lack of addiction services nationwide and economic factors like poverty and unemployment. Canadians are among the world’s highest per capita users of prescription opioids. Widespread prescription use of drugs like morphine, oxycodone and hydromorphone has paved the way to unanticipated levels of addiction. With injectable fentanyl now available on the street (and contaminating large amounts of street heroin), licit and illicit opioid users are at an ever-increasing risk of tragic outcomes. Owing to extensive media coverage, most Canadians have become familiar with this face of the crisis.

And yet in every province and territory there are places where morbidity and mortality from injectable opioid use and abuse have been an inevitable part of everyday life for quite some time but have received limited recognition: Canadian federal penitentiaries. There the crisis is out of sight and out of mind.

Despite the zero-tolerance drug policy of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), drug use is rife in prisons and, unsurprisingly, so is sharing needles. Almost 50 percent of male prisoners have an alcohol or substance use disorder. A 2007 survey of federal prisoners showed 17 percent of men and 14 percent of women had injected drugs within the previous six months, and about half of them shared needles. From 2014 to 2016 alone, the CSC reported 27 overdoses of fentanyl and at least six deaths due to fentanyl. Moreover, prisons are disproportionately populated by individuals from marginalized groups, including Indigenous people and those struggling with mental illness. This is of particular significance because mental illness and drug abuse are known to coexist.

But overdose figures do not tell the whole story about the crisis facing prisoners. Transmission of infectious diseases — namely, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among drug users in prisons. Without sterile equipment, prisoners share needles and fashion makeshift ones, facilitating the spread of infection. Although some prisoners are currently given bleach to disinfect needles, it has been shown that this practice is quite ineffective. Studies are few and far between, but published estimates state that 23 to 87 percent of federal prison inmates are infected with HCV. The rate of HIV is estimated to be about 5 percent. What remains clear is that HCV and HIV rates in prisons are unacceptably higher than in the general population.

Poor health outcomes from opioid misuse and abuse highlight the need for urgent revisions to Canadian drug policies. For the majority of Canadians, change is in the air: in a bid to erase years of draconian Conservative drug policies, Health Minister Jane Philpott announced the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy, which makes it clear that harm reduction is now the order of the day. The Liberals have streamlined the process to open supervised drug injection sites. Opioid antidotes are more accessible than ever. The long-overdue Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act now gives immunity from drug possession charges to those who call 911 to report an overdose. These measures are a good start, but they will do little to improve the health of opioid users behind bars. Canadian prisoners should also benefit from harm reduction policies during this supposed golden age of evidence-based Liberal public health policy. After all, a decades-old and still growing body of evidence shows that harm reduction strategies like opioid substitution therapy (OST) and needle and syringe exchange programs are good for prisoners too.

OST offers prisoners access to opioid replacements like buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone, reducing their reliance on illicit substances like heroin and fentanyl. This approach is increasingly used in outpatient medicine settings across Canada (although we still have a long way to go). Recently, British Columbia paved the way to making life-saving opioid treatments accessible to prisoners in provincial prisons. Roughly one-third of BC’s 2,600 prisoners now have access to buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone through OST.

Prison-based needle and syringe exchanges, which give sterile injection equipment to prisoners, were introduced in Switzerland and have been rolled out in nearly a dozen countries. They are endorsed by over 200 organizations across Canada, in addition to the Canadian Medical Association, the World Health Organization, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Correctional Investigator of Canada. The evidence for these exchanges is compelling: they reduce the spread of infectious diseases due to needle sharing; increase the number of prisoners seeking drug-related treatment; and reduce overdoses. Moreover, contrary to the official view of CSC, the Public Health Agency of Canada has concluded that access to sterile injection equipment does not compromise the safety of prisoners or prison staff. The law and order arguments we are usually fed are baseless: exchange programs have not been shown to increase drug use — in fact, quite the opposite. There is also compelling evidence that such preventive programs can be cost neutral or may even save the federal government a few dollars.

Prison health is part and parcel of public health. The reality is that most Canadian prisoners do not spend the rest of their lives in prison. Those who do return home with communicable diseases like HIV and HCV represent a failure of preventive health care, as these people directly impact the health of those around them. Treating prisoners with addictions and infectious diseases is strikingly more difficult outside prisons than it would be when they are under the supervision of our government. Moreover, prisoners do not give up their lawful right to access health care that is equivalent to what is available for Canadians who are not living in prison. In an effort to confirm this right, a formerly incarcerated Canadian and the HIV/AIDS Legal Network launched a lawsuit against the Government of Canada in 2012 to force it to permit needle and syringe exchange programs in prisons; the case is ongoing. Surely, legal protections preserved in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms are liberties Prime Minister Trudeau is keen to uphold.

The political climate has never been so fertile for progressive and cost-saving harm reduction measures to protect and promote the health of those on both sides of prison walls. Although the evidence is in front of us, no federal political party has made the case for harm reduction measures in Canadian prisons. While the federal government responds to a mounting opioid crisis in cities across Canada, we must not forget the opioid users behind bars. This Liberal government has repeatedly promised us evidence-based policy. So what are Prime Minister Trudeau and Minister Philpott — a physician herself — waiting for? Every Canadian deserves to benefit equally from the government’s new and improved approach.

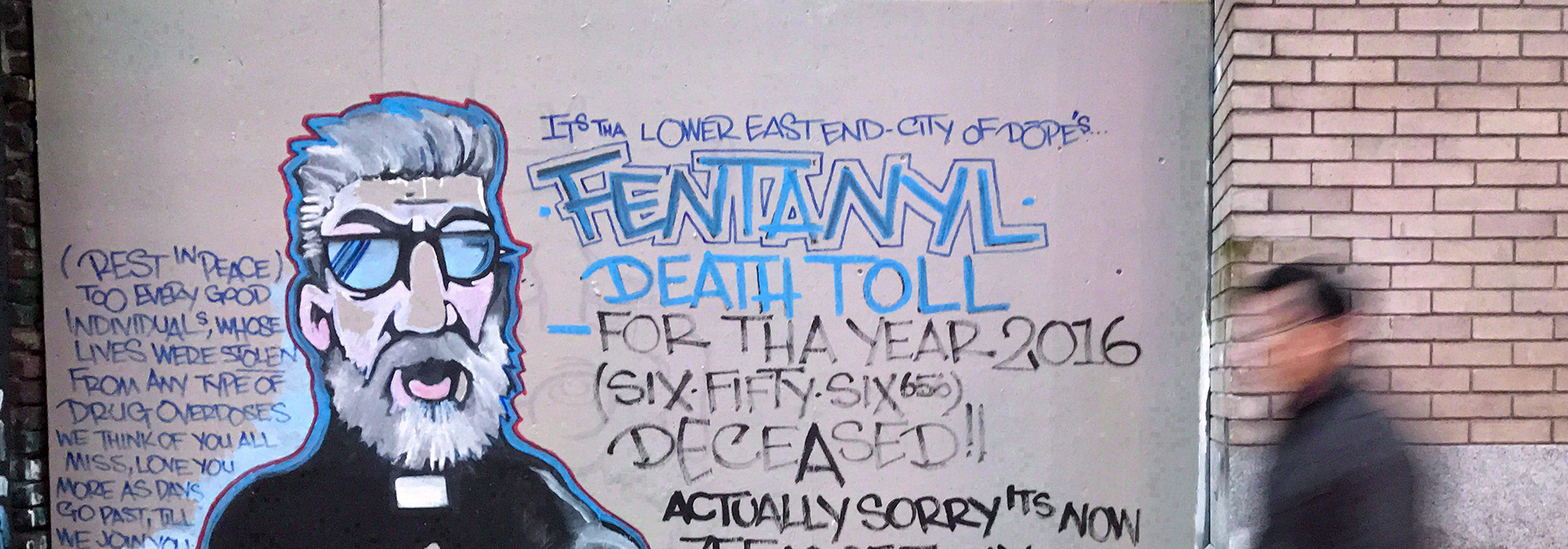

Photo: A man walks past a mural by street artist Smokey D. painted as a response to the fentanyl and opioid overdose crisis, in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, British Columbia, on December 22, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.