While the successful negotiation of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement is a relief, a large bilateral trade issue remains for Canada and the US. The tariffs placed on Canadian iron, steel and aluminum this year by President Trump for national security reasons will stay in effect even though a free trade agreement has been reached. While discussions about these tariffs seem possible, the US sees them as on a completely separate track from the USMCA. The new agreement —which will not be voted on by the US Senate until there is a new Congress next year — does not mean these tariffs will be eliminated and does not protect against the threat of future such tariffs.

Trump’s trade tactics during NAFTA negotiations hurt Canadians and will likely have lasting effects. Our analysis of recent Canadian trade data shows that the impact of the tariffs on Canadian iron, steel and aluminum exports to the US is already visible.

Iron, steel and aluminum tariffs: A case study

On May 31, 2018, President Trump issued two presidential proclamations, placing a 25 percent import tariff on Canadian iron and steel and a 10 percent import tariff on Canadian aluminum.

Our key finding is that these tariffs are having a clear, discernible and statistically significant depressive effect on these exports to the US. We estimate the loss in June, the first month with the tariffs, at approximately $600 million.

We also assessed whether the trend from May to June 2018 for these tariffed goods was comparable to the trend in past periods, and whether the drop could be accounted for by factors such as potential speculation, exchange rate effects and seasonality. The findings did not reveal other explanations for the decline. Further, our preliminary analysis of July 2018 trade data suggests that the depressive effect on Canadian export levels may be sustained, which raises questions about Canadian industries’ capacity to bounce back from Trump’s tariffs.

Two additional points are worth noting. The impact of tariffs depends in part on the type of goods targeted. Iron, steel and aluminum are intermediate goods: that is, they are inputs into other key industries. In fact, most Canada-US bilateral trade takes place across highly integrated supply chains and consists of trade in intermediate goods. As a result, tariffs on intermediate goods can affect competitiveness in a range of other sectors (such as autos and aviation). The additional costs of these tariffs are eventually passed on to consumers, although there may be a time lag.

None of this is good news for Canadian businesses, investor confidence or the public. The imposition of the May tariffs was part of a broader strategy of squeezing Canada’s negotiating position, and it seems to have worked.

Canada retaliated by imposing its own tariffs on US exports of iron, steel and aluminum, which went into effect on July 1, 2018. Our preliminary analysis of their impact suggests that they too are having a significant depressive effect. In contrast to Canada’s industries, however, the larger US sector likely has a greater ability to absorb such effects on its exports.

Canadian negotiators arguably gave in much too generously to US demands. They sacrificed the dairy industry, abandoned the “progressive trade agenda,” accepted the unprecedented clause that requires parties to notify each other before launching trade talks with “non-market” economies, failed to modernize labour mobility and capitulated on the sunset clause.

Yet tariffs on iron, steel and aluminum remain. Canadian negotiators not only should stand steadfast on the demand that these tariffs should be removed immediately, but should advocate strongly for specific and actionable assurances that such measures will not be used in the future.

In late October, Ottawa will host the “Save the WTO Summit,” a gathering to which 13 like-minded countries are invited but, notably, not the US. Saving the World Trade Organization may be a noble endeavour, but the need for this effort just shows how anachronistic the current global trade rules are.

Times have changed. The prospects of saving NAFTA were bleak right from the start; we should remember that in the campaign that brought Donald Trump to power, both parties adopted explicitly anti-free-trade positions. Canadian policy-makers, trade strategists and the corporate community must recognize the new reality and plan to compete in a future where global trade simply may not be as “rules-based” as in the past. This requires thinking much more proactively about domestic sector supports and fiscal countermeasures to both protect Canadian businesses and help level the playing field for them.

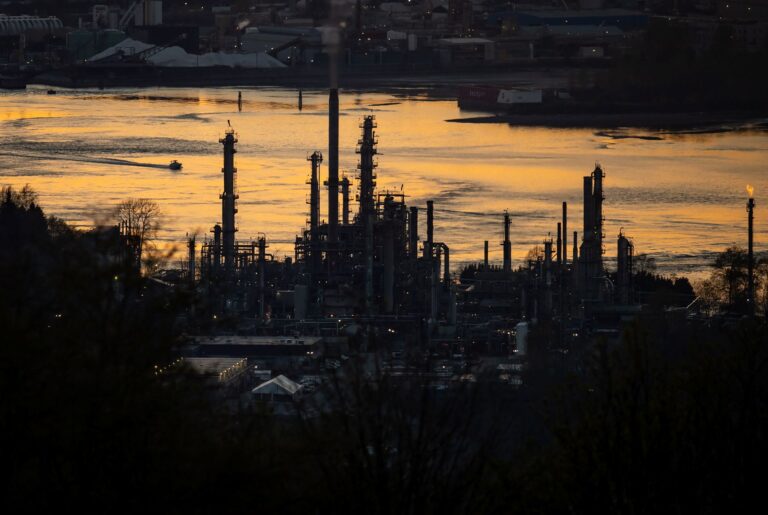

Photo: Chrystia Freeland, Minister of Foreign Affairs, on Friday, June 29, 2018 met with employees at Stelco, in Hamilton, to announce Canada’s retaliatory tariffs on US goods in response to tariffs the US imposed on Canadian steel and aluminum in May 2018. The Canadian Press, by Peter Power.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.