Campaign managers are the central administrative actors in Canadian constituency campaigns, and they perform numerous and varied tasks both in the lead-up to and during these campaigns. Here we explore the three central challenges that campaign managers juggle: managing downward (the local campaign), managing upward (the candidate) and managing outward (relations with the national campaign).

Managing downward – or the local campaign – is the most important and demanding function of a campaign manager. The campaign team and its resources must be garnered, organized and mobilized to focus on helping to elect the candidate. Constituency campaign teams consist of both secondary workers and sympathizers, who perform a range of both specialized and nonspecialized tasks. Some campaigns have several specialists who manage teams of their own. These include sign chairs, who oversee the distribution and maintenance of election signs, field captains, who take the lead on canvassing, and office managers.

The presence of several specialists, who report to the manager and direct teams of volunteers, is a sign of a professional campaign. Managers try to delegate tasks to specialists and do not involve themselves in the day-to-day minutiae of the campaign, instead taking a broad strategic view of activities and focusing on managing the candidate and the relationship with the national campaign.

Most functioning campaigns have such specialists, but they may not be paid positions. Where there is no expertise available, the campaign manager may end up taking on some or even most of these tasks. Directing even a modestly sized team of volunteers can easily consume a manager’s time. In campaigns that are not well staffed, the manager may even end up performing tasks normally reserved for volunteers.

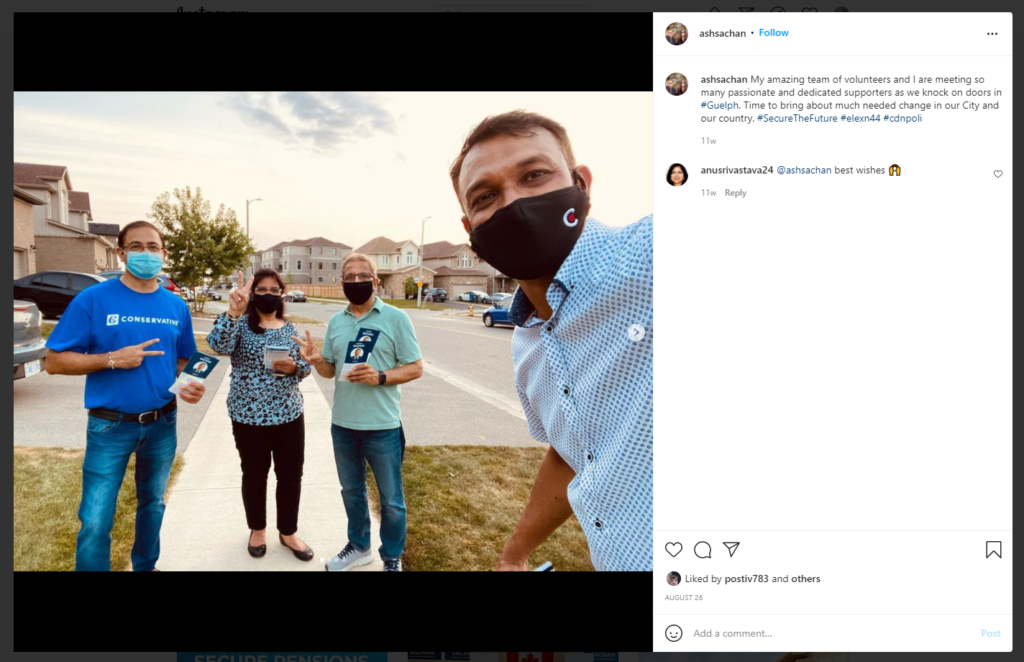

All serious campaigns include volunteers, whether they are only a handful of friends and family members or an army of grassroots activists. This raises two issues for campaign managers. The first is how to co-ordinate volunteers who do not show up regularly. Volunteers who show up unannounced and unpredictably contribute to the chaotic nature of constituency campaigns. The campaign needs to either reject these offers of time or be flexible and imaginative enough to make sound use of volunteers’ time and skills.

Campaign managers must also provide benefits that sustain volunteers beyond whatever initially drew them to the campaign. Most campaign managers report that keeping spirits high is an important aspect of the job, as is thanking volunteers and building a sense of community among campaign workers. Occasional pizza in the evening at the campaign office can help.

https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/november-2021/inside-the-constituency-level-election-campaign/

The second challenge campaign managers confront is to manage upward, which means managing the candidate. The candidate is the crucial public-facing figure in the constituency campaign, so the candidate’s time and effort must be used wisely. Generally, this is a task that falls to the manager.

It sometimes surprises outsiders that the need to keep candidates productively engaged in the campaign is a central goal for managers. One way they do so is by keeping candidates focused on what they should accomplish. The classic example several campaign managers have relayed to us is of candidates who enjoy hanging out at the campaign office chatting with volunteers. Since there are no votes to be found in the campaign office, the manager must push the candidate out the door and schedule their time so they are canvassing or increasing name recognition by campaigning throughout the constituency.

Just as campaign managers must direct candidates to what is important, it is equally necessary to steer them away from what is not. Candidates running for public office are exposed to a variety of information that can be deflating. Managers try to dissuade candidates from focusing on national polls or bad news stories – especially negative stories in local newspapers – or, worst of all, angry comments on social media.

A recurring theme when discussing managing upward is the importance of knowing candidates well enough to shape a campaign that makes use of their strengths while avoiding activities with which they may struggle. Other times, problems must be addressed. Sometimes candidates are bored by policy platforms and never-ending arguments about policy, so managers must encourage them to be sufficiently informed to be able to talk about these issues on doorsteps. Or, candidates might not enjoy shaking hands and other trappings of the local campaign, so the manager must gently push them toward doing so and provide encouragement. More frequently, candidates run themselves ragged, and campaign managers have to intervene and insist that the candidate take a day off to recuperate.

In all cases, the goal in managing upward is to create trust between the campaign manager and candidate, which provides the basis for the campaign to function smoothly. Candidates must be able to trust their managers and accept criticism. Candidates who trust that the administrative aspects of their campaigns are well-managed are free to focus on reaching out to voters. At the same time, managers must be willing to intervene when necessary and believe that their views will be heard and respected by the candidate.

The third challenge campaign managers confront is managing outward, the relationship with the national campaign. Constituency campaigns may benefit from the national campaign providing money or other resources such as volunteers. National campaign co-ordinators will sometimes direct volunteers from one seat to another if it is determined that a seat is marginal and can be won with additional effort. Local campaign officials can also benefit from guidance provided by experienced campaign professionals in the form of workshops or weekly telephone briefings.

Campaign managers at the grassroots level are typically assigned a provincial or regional representative of the national campaign who is responsible for interfacing with the constituency campaigns within their regions. The national campaign tends to leave local officials alone if things are going well, but will provide services if asked.

On the other hand, national officials will sometimes intervene if local officials are having difficulties. If constituency campaigns are not meeting their targets with respect to canvassing, a national official will be in contact to encourage volunteers to move quicker when door knocking. Campaign managers will bear the brunt of this hectoring and must contemplate how or whether to follow the national campaign’s guidance. In addition, friction between the constituency and the national campaign can develop if the national campaign or the party leader performs poorly, and gives the impression that the local candidate is being dragged down.

The first loyalty of campaign managers is typically to the candidate and the constituency campaign. This means that when the interests of the national and local campaigns diverge, the manager will side with and protect the interests of the constituency campaign. But campaign managers are not generally or reflexively belligerent toward the national campaign, recognizing that one of their roles is to act as an intermediary between the local and national levels for the overall benefit of the local campaign.

This article is abridged from a book that UBC Press plans to publish in 2022. It is part of the Inside the Constituency-Level Election Campaign special feature series.