The public policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic was one of the largest peacetime challenges for government in modern history. The pandemic threatened the life of every person and placed unprecedented demands on political leaders and public officials at all three levels of government. The pandemic also occurred in an age of social media, where information and misinformation spread quickly, and where anonymity has empowered the darkest corners of society.

It’s easy to forget the tremendous uncertainty that came with COVID-19. Scientific and medical experts were working around the clock to understand the virus. People were being infected and doctors were learning how to treat them. Pools of subject-matter experts, researchers and every-day citizens were calling for immediate action. As if this wasn’t demanding enough, then-U.S. president Donald Trump, who was the most powerful leader in the democratic world at the time, was musing about whether people should try “injecting bleach.”

The pandemic also had an impact on trust. While the enormous stress it created in public confidence was deeply worrying, it also opened a unique window into Canadians’ psychology, our most resilient beliefs, and what our society is capable of tolerating and willing to forgive.

We can inoculate ourselves against COVID-19 misinformation

Pandemic puts public trust to the test

What we can learn from COVID communications in other countries

That insight will be critical for decision-makers to chart a path for Canada at a future turning point: when misinformation is increasingly pervasive; when generational shifts are hastening; and when societies are fundamentally transforming due to government response to climate change.

There are three things that can be done to prepare for the next crisis: teach younger Canadians in particular how to distinguish between disinformation/misinformation and reject it; invest in the training of trusted family doctors and nurse practitioners; and develop deeper legislative and policy partnerships between federal and provincial governments.

Three phases of pandemic trust

In conducting our CanTrust Index™ study for almost a decade now, we saw wider swings and higher volatility than normal in each of our annual surveys from January 2020 to January 2023. Any crisis brings volatility in trust. The Dutch proverb still rings true: “Trust comes in on foot and leaves on horseback.”

In Canada, we saw three phases of public sentiment and trust during the pandemic.

In the first phase, there was a rallying around science. It’s an admirable and practical approach, indicative of the majority of Canadians. Trust in scientists and medical doctors spiked to unprecedented heights – around 80 per cent in our tracking research. Recognizing the mood, federal and provincial elected officials rarely appeared without a physician beside them.

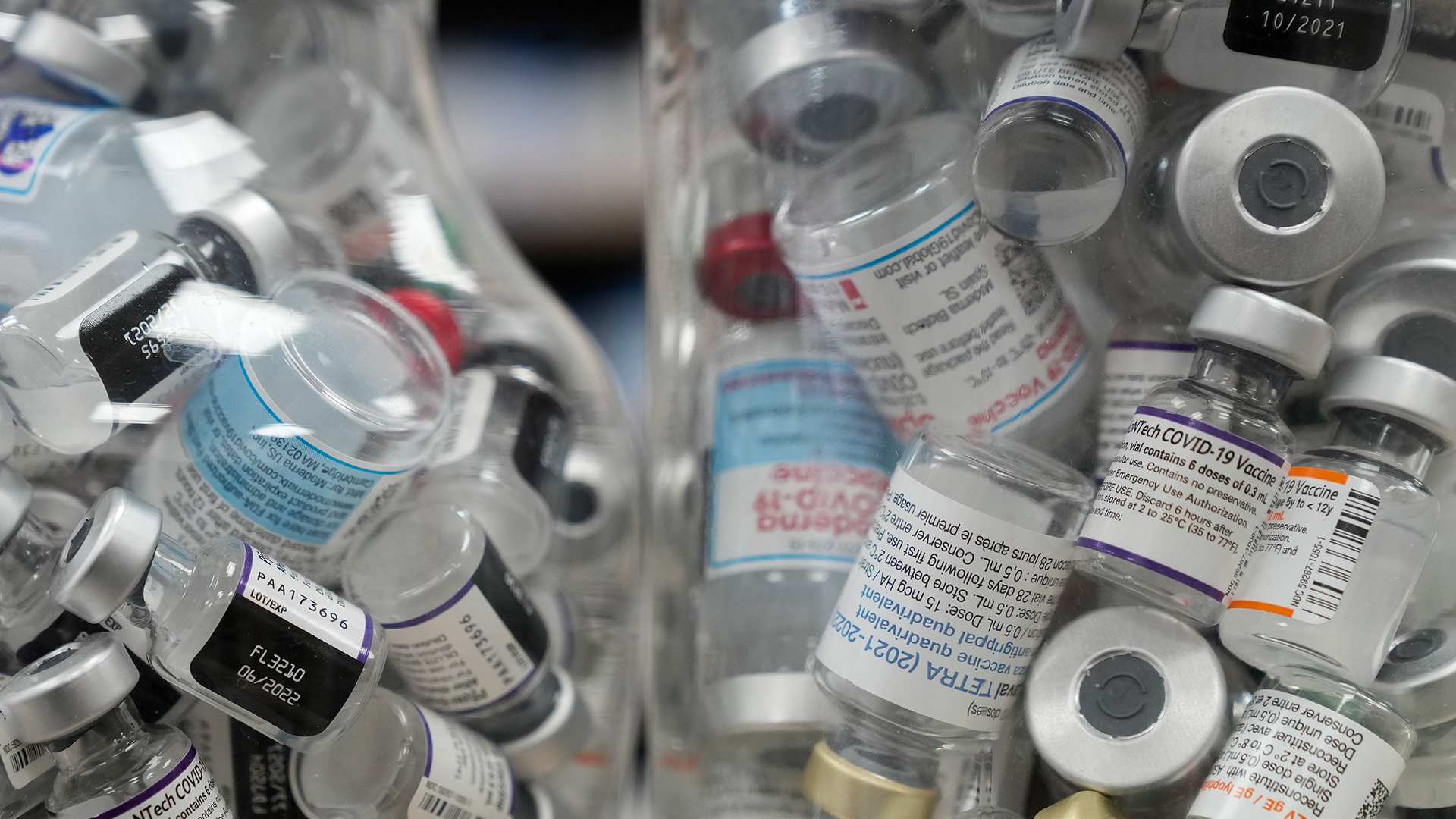

In the second phase, we had the vaccine race. Governments scrambled to obtain doses in a less-than-free global market. Opposition parties focused on how fast doses could be delivered, not the merits of the vaccine. Vaccines were seen as the panacea. Once again, the trust of Canadians in vaccines was high – in the 80 per cent range.

In the third phase, we saw fatigue. Canadians were tired of lockdowns, separation from their loved ones and limited travel. Vaccination rates reached impressive levels; however, as the end seemed near in late 2021, the Omicron variant stormed onto the scene and reversed the sense of progress.

Looking back

In our January 2023 study, the benefit of hindsight had set in among Canadians. About one-third, or 36 per cent, agreed that “governments struck the right balance in managing the pandemic, promoting safety measures and using restrictions.” Slightly more than one-quarter, or 28 per cent, took the opposite view, agreeing that “governments added too many rules and were too slow to remove safety policies as vaccines became available.” Notably, 20 per cent of Canadians said governments “should have done more to maintain safety and require vaccinations.” (The other 16 per cent were unsure.)

In sum, a very comfortable majority of decided Canadians believe that governments struck the right balance, or could have done more, to maintain safety. That acceptance is notable: it fits with the re-election of several Canadian governments in various jurisdictions during the pandemic.

Despite this majority sentiment, there was a highly vocal and active minority opposed to various pandemic management efforts. This minority included people opposed to vaccines in general and others who opposed requirements for mandatory vaccinations. In parallel, pitched political rhetoric on the subject – from different points on the spectrum – boosted tension. It will not be as easy for governments to impose restrictions and mandatory requirements in any future pandemic. We can also be certain that misinformation will abound, likely empowered by artificial intelligence.

There’s a parallel track. The outbreak of the pandemic effectively overlapped with the coming of age of a new cohort of Canadians: Generation Z, those born after 1997. The 2023 CanTrust Index data showed a notable drop in trust levels amongst both Gen Z and millennials when compared to Boomers. The spread of increasingly sophisticated misinformation risks eroding the younger groups’ trust even further.

Misinformation gets around

False news online travels “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth,” according to a study of Twitter released in 2023 by staff at MIT. This observation is more pronounced for false political news than for false news about other topics.

Falsehoods are 70 per cent more likely to be retweeted on Twitter than the truth, researchers found, and false news reached 1,500 people about six times faster than the truth.

Whose job is it?

An interesting question is who is responsible for stopping misinformation. A 2022 Léger Marketing study, in partnership with the Institute for Public Relations and McMaster University, found that more than eight in 10 Canadians said their provincial government (83 per cent) and journalists (83 per cent) should be responsible for combatting disinformation. The same research showed a lack of confidence, with fewer than four in 10 saying their provincial government (38 per cent) and journalists (36 per cent) were combatting it at least “somewhat well.”

What to do

There will be future pandemics, growing pressure on our health-care systems and other crises. The entrenched and vocal views that emerged during COVID-19 offer a clear sense of future challenges. To give Canada a chance of managing any future health crisis, and the ongoing misinformation crisis, we present three ideas:

1. Implement curriculum reform in classrooms and mount education campaigns across the nation on media literacy, digital deep fakes and fact-checking. Canadians of all ages need to be armed with the tools to consume modern information with a critical eye. The kindergarten teacher is where it should start, and methods should be tailored for each generation’s needs and habits. Media outlets also have a role to play in amplifying important voices on this topic. More subject-experts need to be given the platform to educate the public on misinformation so that all Canadians are equipped to root out what is true from what isn’t.

2. Invest in the recruitment, retention and education of family doctors and nurse practitioners. Our research shows that 73 per cent of people trust their doctor, but too many don’t have one. When the next health crisis occurs, these relationships will be the educational antidote to fears and misinformation campaigns.

3. Establish a co-ordinated legislative and policy partnership between Ottawa and the provinces to use all the legal tools possible against false information, including misrepresentation of people or organizations. This should be respectful of each jurisdiction’s responsibilities and sensitive to freedom of speech. It is feasible: Canada’s governments worked together to meet the moment during the pandemic and can do so again. Collaboration with other democracies should also be a part of the plan. Canada has invited G7 nations to the table to develop an international set of tools and programs to tackle disinformation – and should continue to move this forward. Advisors from the private sector can help guide legislation, but we should be wary of the motives of some social media companies.

For all its destruction, the pandemic also delivered the experience, insights and perspective Canada needs to face the next round of challenges. Decision-makers, public officials and Canadians would do well to take heed.

To learn more about the 2023 Proof Strategies CanTrust Index, visit www.cantrustindex.ca.