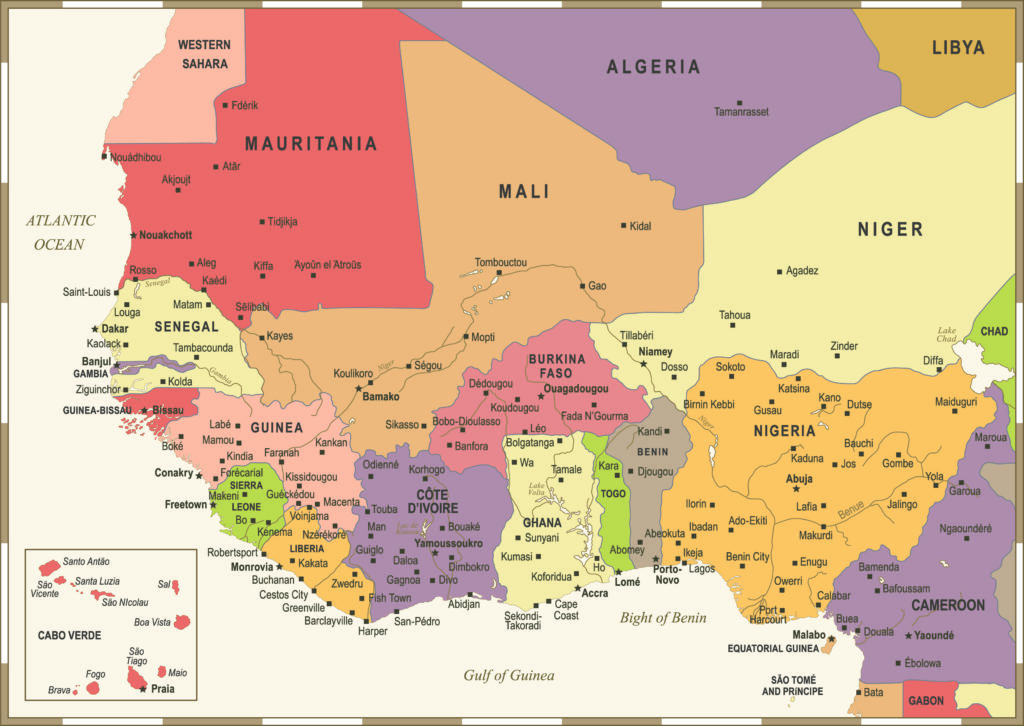

The rapidly deteriorating situation in Mali unequivocally points to the dismal failure of international intervention. The current crisis started with the August 2020 military coup d’état, which marked the first obvious evidence of that failure. It was followed by a second coup in May 2021, when the junta arrested the country’s president, the prime minister and the defense minister.

By the end of 2021, the junta had asked France to revise its military co-operation accord, had reached an agreement with the Russian private security group Wagner for the presence of 500 troops – seemingly in exchange for mining concessions – and had declared a four-year transition government before holding an election. This was apparently the last straw. In January 2022, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) imposed economic sanctions and closed its borders with Mali. And in late February, the French and other Europeans pulled out their troops.

As a January Globe and Mail story put it, Canada “is still considering its options.” Canadian police, military and civilian personnel have stayed and continue to support United Nations and Malian peacebuilding efforts. This is not surprising. It is doubtful that joining in the sanctions would have added much to change the situation. Canada leaving the country would have amounted to an overreaction. The UN and many Malians still need help and support, and the UN isn’t going anywhere. If you want to pressure the junta, you want to stay to keep the pressure on.

But what about Russia? Much has been said and written about the so-called return of Russia to Africa – and the invasion of Ukraine is certainly another twist to the story. As the European Union warned Mali over the use of Russian mercenaries, should Canada and its allies be worried? What impact can a private security group like Wagner truly have on the situation in Mali, especially now that the French and European counterterrorist forces are gone?

Russians in Mali

In Bamako, Mali’s capital, and other cities and towns, massive rallies have demonstrated that Malians are fed up with France, the UN, and ECOWAS. The junta is popular. Its overtures to Russia and the Wagner group are presented as better options and as the exercise of Malian sovereignty.

In Paris and other Western capitals, the Wagner issue is overblown. Yes, Moscow might want to see Western allies fail – not only in Mali but in the larger West African Sahel. Yes, the Wagner group brings increased risks and uncertainty. Its practices are problematic on several counts as seen elsewhere, like in the Central African Republic. At best, Wagner soldiers won’t exacerbate conflict dynamics in the central and northern regions of Mali. If the junta believes otherwise, its leaders are not who we thought they were.

What Wagner does is to contribute to larger political tensions and struggles and support populist tropes. Wagner and the reactions to its deployment are more the symptoms and consequences of a decade-long deteriorating situation and of the failures of international intervention more than anything else. In this sense, the consequences will partly depend on what others will make of it.

Russia, Wagner and the reactions speak to Malian internal politics, to forms of (largely anti-French) populism and to the tactics of Malian elites battling over public opinion and support. In the 1960s and 70s, Mali developed relations with the Soviet Union as an alternative to the West, but without closing the door to France and the advantages of the special relationship between France and Francophone Africa. In populist fashion, the Wagner group speaks to this nostalgia of the “special relationship” between Mali and Russia as an alternative to France.

Long story short: there has always been a strong anti-French sentiment in Francophone Africa, as a consequence of colonial rule. French military operations in Mali – the January 2013 Operation Serval, later transformed into Operation Barkhane – were different, but nevertheless often patronizing. They were run like technical matters that were conceived of as separate from Malian politics and social dynamics.

In 2022, Operation Barkhane had become the symbol and expression of the limits of French influence and power. Most importantly, it demonstrated the limits of military intervention to solve political and security crises. French operations came to represent the failures of the international intervention and imagination and as such easily portrayed as responsible for the lack of progress in solving the conflict.

Endgame

“Russian manipulation” can not be attributed to Malian dynamics, actions and decisions. As Bruce Whitehouse put it, “what if real sovereignty means the freedom to make one’s own mistakes, and to say ‘No’ to whomever one wishes?”

Indeed. All of it is being and will be played out internally in Mali, albeit under the parameters and limits established by the international politics of intervention. Those parameters and limits are not set in stone or all-powerful. Malian actors push against the boundaries, negotiate what they can within limits, or challenge those limits, just as they can also write their own.

It is a struggle between national sovereignty and international authority and for some Africans a decolonization process 2.0. Everyone agrees that general conditions in Mali have steadily been getting worse since 2015. International actors have argued that the problem is largely found in Bamako: a matter of poor or corrupted governance.

To some extent, the junta agrees. That was the basis of the justification for two coups d’état. But it also argues that international conditions have sustained and contributed to governmental corruption and ineptitude. Hence, the need to radically transform and push against international conditions and reclaim Malian sovereignty, especially in the face of some international partners who stubbornly refused to change their approach, until they left Mali.

In this struggle, for the junta Wagner and Russia are tactical options and tools. Cards that can be played against other international actors and one that is winning over public opinion as it feeds into the populist nostalgia about Mali’s glorious past.

This is a dangerous game that the junta is playing, even more so now as Russia has lost most of its international credibility after the invasion of Ukraine. By using populist tactics and calling Moscow, the Malian junta created space and opportunities to renegotiate the parameters of international intervention.

With the invasion of Ukraine, it is too soon to know precisely what consequences it will have on the Malian junta’s Russian gamble. Much will depend on Malian understanding and perceptions of events in Ukraine. One thing we know is that Mali abstained on the March 2 UN General Assembly resolution demanding the withdrawal of all Russian military troops from Ukraine. It was also reported that, a week later, the Malian minister of defense, colonel Sadio Camara, and the air force chief of staff, colonel Alou Boï Diarra travelled to Russia to discuss Russian arms transfers.

In the short term, the invasion of Ukraine is unlikely to change the Malian junta’s position or tactics. But if Russia pariah status is sustained in the coming months or years – and every indication points that it will – Bamako might want to distance itself from Russia, revisit or annul its contract with the Wagner group, or risk alienating its African and international partners. Outside populist circles, a pro- or moderate position toward Russia might prove unsustainable in the face of international pressures to condemn Moscow.

The French Barkhane and European Takuba forces are gone, taking with them much-needed troops, equipment and funds. This leaves the junta with unknowable and unreliable Russian mercenaries, and with jihadist insurgencies throughout the country that they can’t control or manage with populist tactics.