Canada’s private refugee sponsorship program has been widely celebrated in recent years as a unique policy framework that allows citizens to actively participate in the process of refugee protection. Sponsors commit to providing funds to cover the first year of settlement in Canada, while the government provides health care, education, language training and some other costs. The popularity of this policy meant that more than half of the Syrian refugees who recently arrived in Canada came under private sponsorship. Next year, the Government of Canada expects private sponsors to take responsibility for resettling almost twice as many refugees as the government itself.

Private refugee sponsorship remains a uniquely Canadian policy, despite efforts to export a version of it to other countries. While some romanticize the success of the policy as a reflection of our national virtue, the roots of the program suggest a more tenuous path of development. In my book, Send Them Here: Religion, Politics, and Refugee Resettlement in North America, I explain why and how Canada developed private refugee sponsorship. At the centre of this story is the creative and humanitarian role played by religious groups and coalitions. Religious groups continue to be leading actors within Canada’s resettlement programs and it’s important that the government recognize their role.

Many scholars trace the origins of private sponsorship to the Indochinese refugee program in 1979 – a milestone moment in the development of Canadian immigration policy. However, the program itself originated in the years after the Second World War.

After the war, a number of religious groups – Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant – negotiated an arrangement with the Canadian government to sponsor displaced people with relatives in Canada. This family sponsorship program evolved into the “Approved Church Program,” in which a handful of religious groups were authorized to select and resettle refugees as long as they paid their first year of settlement costs. This program introduced the concept of “naming” into Canadian private sponsorship, which allows sponsors to identify – by name – the refugees they resettle. It also created the financial liability of sponsors for the first year of settlement costs.

A two-track refugee program emerged during this time: one led by these religious groups and another government-run program targeting economic needs. The tension between the two was captured by remarks by Saul Hayes of the Canadian Jewish Congress, in a meeting with the immigration minister in 1956: “Immigrants should be regarded from the humanitarian as well as the economic point of view… Canada has obligations in the post-war world…and we shouldn’t look at immigration solely from the point of taking the very best people out of Europe.”

On the other hand, Canadian immigration officials grew resentful of the involvement of religious groups in selecting refugees to sponsor for resettlement in Canada. One wrote to the director of immigration that they “appeared almost to specialize in undesirable immigrants of this kind…the final, ultimate dregs, the scrapings of the very bottom of the barrel.” He continued to assert the view that “every immigrant should possess some desirable qualification, at the very least.”

The tension between the humanitarian ethos espoused by sponsoring groups and the economic imperatives followed by immigration officials eventually led to the end of the Approved Church Program in 1958. Scarcely a few months later, however, a private sponsorship program was revived in time for World Refugee Year in 1960. The purpose of that program was to mobilize Canada’s religious communities to sponsor elderly or disabled refugees in Europe who still remained displaced, 15 years after the conclusion of the war.

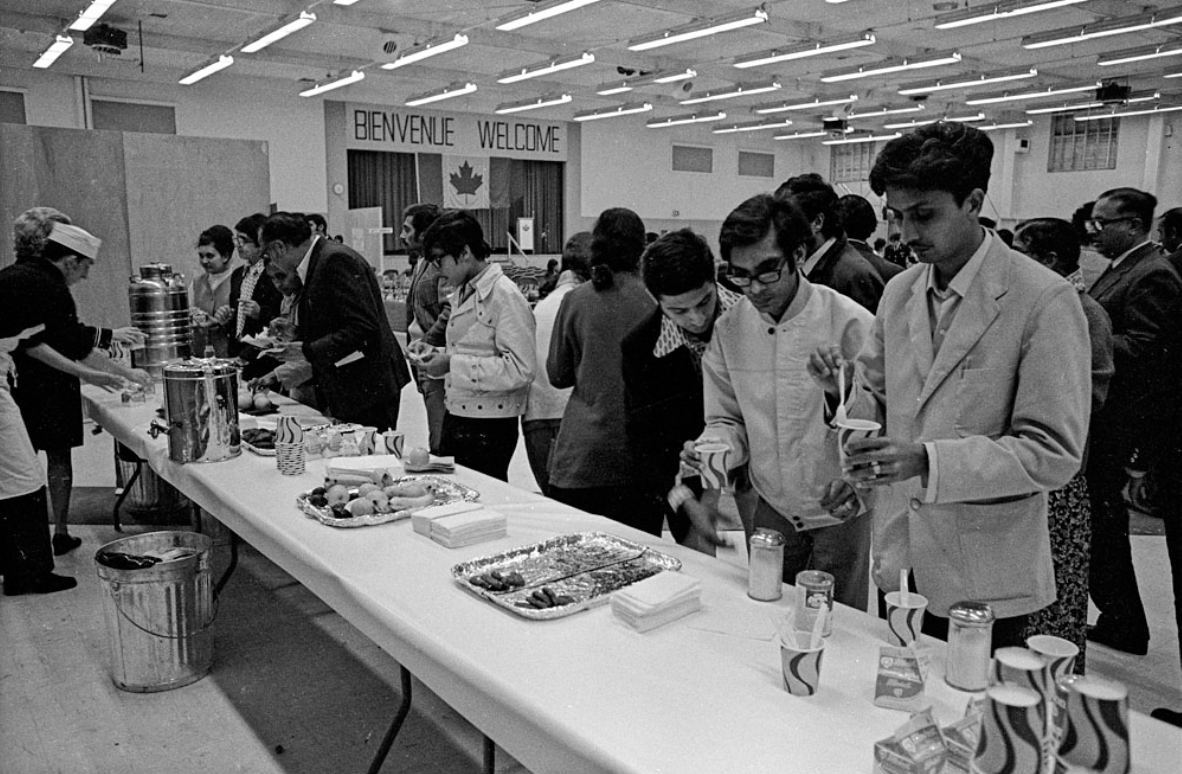

During the 1960s, Canada’s early private sponsorship program fell into disuse. The then-minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Ellen Fairclough, was said to be “suspicious and wary” of cooperation with the religious groups. The feelings appeared to be mutual. With the exception of a small program to sponsor Jews fleeing the Soviet Union, resettlement programs for Czechoslovakians and Ugandan Ismaili refugees were principally led by the government (with an eye towards Canada’s economic interests).

In 1973, Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s government initiated a process of immigration policy reform that included broad-based public consultation and input, centred on a government Green Paper. These public submissions included one by the Jewish Immigrant Aid Service (JIAS) that proposed that “individuals, or responsible voluntary social agencies…offer sponsorship or co-sponsorship” of “humanitarian immigrants.” As one of the only groups to maintain a private sponsorship program during the 1960s, it is not surprising that JIAS recommended its inclusion in the 1976 Immigration Act. After the Act came into effect, JIAS was approached by immigration officials to carry out the first pilot program under the new legal provisions.

As refugees began to flee from Indochina in the late 1970s, however, it was the Mennonite Central Committee of Canada (MCCC) that approached the Canadian government with a proposal to create a clear policy framework around private sponsorship. Their negotiations created a structure of formal agreements that clarified the financial responsibilities of sponsors and guaranteed government support for education and language training.

These formal arrangements – called master agreements – were eventually signed not only with the MCCC, but with some 40 other religious organizations. Indeed, the creation of these agreements provided the backdrop for the later government commitment to resettle more than 60,000 Indochinese refugees in a one-for-one matching scheme with sponsors.

Canada’s private sponsorship program is currently in the middle of another renaissance, and religious groups remain at the centre of the program. Of about 120 Sponsorship Agreement Holders, around 90 are affiliated with a religious community. The future success of private refugee sponsorship – in Canada, as well as in other countries currently studying the model – will be predicated to a large extent on support from religious groups.

Recognition of this fact is important if the government is to accurately perceive the potential that exists in society for humanitarian action. Religious groups are effective at private sponsorship because they motivate their community members through appeals to shared spiritual principles and have the structures and resources that can be mobilized into the field of social action. Not only could Canada’s private sponsorship program fail to function without the support of religious groups, but it is also entirely unlikely that it ever would have been created without them.