The Internet, as a tool for on-line campaigning, is a moving target. The “killer app” for campaigners appears to change from election to election. Campaign Web sites and on-line fundraising were new and novel in 2000. While major and minor Canadian political parties had established campaign sites, they failed to take advantage of the full potential of the medium. By 2004, Howard Dean’s success with Blog for America had made political parties and candidates jump on the blogwagon. In the 2004 federal election, Canadian sites were more dynamic and integrated into the overall strategy of the parties.

This said, the sites seem to lag behind the American ones in terms of citizen engagement tools. The blogging revolution occurred two years later in the 2006 election, where amateur bloggers, media bloggers and party bloggers covered and discussed the election. This year, there is much talk of the “Facebook effect.” Candidates for election on both sides of the 49th parallel have established Facebook pages to capitalize on the millions of Facebookers. But yet again Canada’s parties have lagged behind those of the southern neighbours.

Facebook is part of a broader transformation of the Internet called Web 2.0. Compared to its predecessor, Web 2.0 is far more collaborative, creative and interactive. Social networking, blogging, microblogging, on-line video sites such as YouTube and social bookmarking sites like Digg are part of the Web 2.0 universe. All of these sites allow users to interact with other users and collaborate in the creation of site content. While Friendster and MySpace launched social networking, Facebook is now the major player. Founded in February 2004, Facebook is a social utility that helps people communicate more efficiently with others. Not only is it the most popular social networking site, Facebook is one of the world’s most trafficked Web sites — period. Initially targeting college students, Facebook has more than 100 million active users, two million of whom are Canadian.

On-line social networking has grown rapidly. A 2007 IpsosReid study reported that 37 percent of Internet-enabled Canadians, 18 and older, had visited a social networking site and 29 percent have placed a profile on at least one such site. One year later an M2 Universal social media survey reports that 59 percent of on-line Canadians have created a social networking profile. Like other social networking sites, Facebook allows individuals to create a personal profile and form links with other users. These links may replicate off-line personal relationships with friends, family, co-workers and classmates, but users may also link with others who share similar interests. Politics is very popular on Facebook. In 2006, the site allowed politicians to create profiles and buy ad space. Like any Facebook user, a politician can provide information about themselves, post photographs or videos, post notes to their supporters and interact with supporters on their wall. Beyond the personal profiles of the politician, there are a growing number of groups dedicated to various political issues forming via Facebook. These groups may or may not have comparable off-line equivalents.

There are clear benefits for a campaign on Facebook; first, a campaign can increase exposure at a low cost or no cost. Moreover, this exposure is unmediated by the press. Second, Facebook provides access to the millennial generation — those born between 1980 and 2000. A study by the Dominion Institute shows that four in five young Canadians aged 18-25 have a Facebook profile. Some see social networking sites as an ideal way to reach young people, who are increasingly apathetic about politics. Third, because Facebook requires the user to request to be a “friend” or supporter of the campaign, a ready-made database is created allowing campaigns to raise contributions and recruit volunteers on-line. Fourth, like other aspects of the Internet, Facebook is interactive. This could potentially allow communication between voters and the campaign and between voters and other voters.

Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama is the newly minted king of on-line campaigning, and Facebook is playing a central role. The hiring of Chris Hughes, one of Facebook’s cofounders, to coordinate his on-line campaign evidences the importance of social networking to the Obama campaign. Obama is clearly winning the Facebook war with Republican John McCain; 2.2 million people have “friended” the Democratic presidential candidate on Facebook, compared to just over half a million for John McCain. Some 500 unofficial Facebook groups are dedicated to the Democratic candidate. One of the oldest Obama Facebook groups, One Million Strong for Barack, is 183,000 short of meeting its goal of one million supporters. Facebook as well as other digital tools such as e-mail and text messages are being used to reach potential donors and volunteers. To date, the campaign has raised than $600 million. Like Howard Dean before him, much of Obama’s money comes from millions of small donors over the Internet.

Has the Facebook effect hit Canadian election politics? A quick search of the term “Canadian election” in the Facebook search engine results in more than 400 groups.

Has the Facebook effect hit Canadian election politics? A quick search of the term “Canadian election” in the Facebook search engine results in more than 400 groups. Moreover, all five of the major Canadian party leaders, as well as thousands of candidates across Canada, posted profiles on Facebook during the recent campaign. However, if the mantra of Web 2.0 is collaboration and interaction, the Facebook sites of the party leaders did not live up to this in the 2008 election. The use of Facebook by the parties was very minimal compared to their American counterparts and even compared to their use of other parts of the on-line campaign.

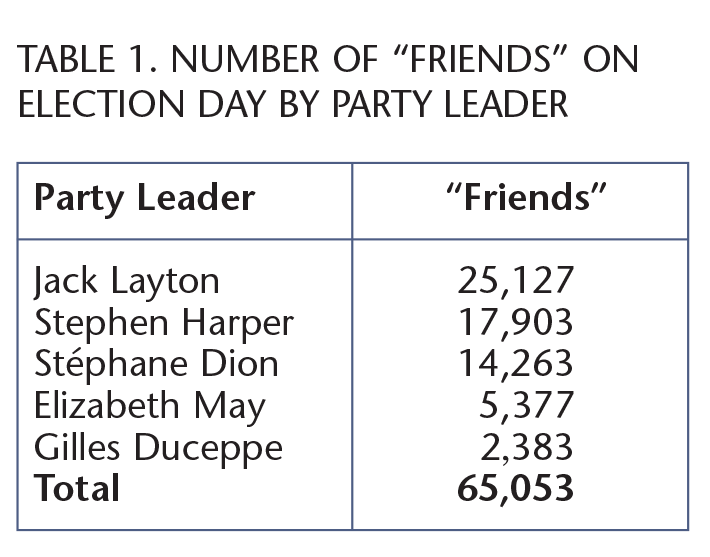

If the highest number of “friends” indicated success in the election then Jack Layton would now be prime minister. Table 1 shows the number of “friends” each party leader had on election day. Canadians did not clamour to “friend” a Canadian party leader in this campaign. The number of Facebook “friends” of the party leaders does not compare to Barack Obama’s or even John McCain’s. Indeed, Facebook “friends” are a small proportion of the Canadian electorate, making up not even 1 percent of those who actually showed up at the polls on October 14. This said, the number of Facebook “friends” of Canadian party leaders did increase over the 37-day campaign by 39 percent. Facebook was used to provide basic information about the leader. In addition to basic contact information, “friends” were privy to some interesting facts about Canada’s party leaders, including that Star Wars is Jack Layton’s favourite movie and that Stephen Harper is writing a book on the early history of professional hockey.

Overall, the Facebook profiles were static and low on information. Whereas hundreds of press releases and reality checks were uploaded to the home pages of the party Web sites, none of it was uploaded to Facebook. Mainly, the profiles featured photographs from the campaign trail and/or the parties’ television advertisements. However, very few of the party leaders took a page from Barack Obama’s playbook, using the direct access to supporters to raise funds and recruit volunteers. Jack Layton sent two notifications, one seeking volunteers and one for fundraising. Stéphane Dion once engaged in viral campaigning by asking supporters to “help us spread the message” by sending a message to others, encouraging them to “friend” the Liberal leader. Beyond these examples, direct appeals for support via Facebook were non-existent in the Canadian on-line campaign. Obama’s fundraising success would suggest that this was a lost opportunity for the political parties. Arguably a Facebook “friend” would be the very type of person who would be willing to donate or volunteer.

With Web 2.0, a politician could use the Internet to allow for considerable participation in the campaign by letting supporters contribute campaign content and interact with the party and with other supporters. Generally, Facebook was not utilized in this capacity. Even though “friends” of Elizabeth May and Jack Layton were able to submit “fan” photos and videos, only a small number of people did so. The wall feature did allow “friends” to post comments to the campaign and for other supporters. By the end of the campaign, some 4,000 comments appeared on Layton’s and Dion’s wall, both May and Duceppe had fewer than 1,000 comments. Interestingly, the Prime Minister’s profile did not feature a wall; there was no two-way interactivity on that site.

A Facebook group called Anti-Harper Vote Swap Canada formed. The group’s mission was to ensure that Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party did not obtain a majority in the 2008 federal election.

Perhaps the most interesting Facebook moment of the 2008 election had nothing to do with the parties at all. Shortly after the writ dropped, a Facebook group called Anti-Harper Vote Swap Canada formed. The group’s mission was to ensure that Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party did not obtain a majority in the 2008 federal election. Using a Facebook application, the group aimed to match up voters in ridings where the Conservatives were in tight races and encourage people to vote for the party most likely to upset the Tory candidate. The only way to participate in the vote swap was to have a Facebook account.

Vote swapping is not a new phenomenon; in both the 2000 and 2004 presidential election campaigns, various Web sites emerged to allow supporters of the Democratic candidates and Ralph Nader to trade their votes. In the United Kingdom, there are even reports that vote swappers using the site Tacticalvoter.net were successful in one riding in the 2001 election. This was, however, the first time that vote swapping came to prominence in a Canadian election and on a social networking site.

Anti-Harper Vote Swap Canada received considerable media attention. The group even prompted an Elections Canada investigation, which determined it is legal and does not violate any electoral laws. A number of Facebook groups formed in opposition, including Anti-Anti-Harper Vote Swap and Voters Against Vote Swapping. This Facebook group was a part of a broader on-line phenomenon of strategic voting Web sites that appeared in this campaign. Sites like www.voteforenvironment.ca encouraged voters to vote “anything but Conservative” or ABC by identifying ridings where the party was vulnerable. By election day, some 13,000 Facebook users had joined the group. With the victory of the Conservative Party in this campaign, the success of Anti-Harper Vote Swap Canada and other strategic voting Web sites is called into question. Given the secret ballot, there is no way of knowing how many members of the Facebook group followed through on their commitment.

The use of Facebook by Canada’s party leaders shares little with Barack Obama’s. However, given the differences in political context, this is not surprising. The United States is a candidate-centred polity with a vastly different regulatory regime and media environment than Canada. It should be expected that these factors would shape how candidates and parties on both sides of the border use the digital technologies. Moreover, given the small number of people who “friended” the party leaders, it may not be surprising that the campaign did not focus much of its precious resources there. It should also be remembered that Facebook was just one part of the sophisticated on-line strategy of the Canadian parties. In addition to their standard party Web sites, several parties utilized other Web sites that had a narrower focus. For instance, the Conservative Party’s controversial Not a Leader site featured the “pooping puffin.” The Liberals created This Is Dion to introduce Canadians to the Liberal leader, while the NDP established a social networking site call Orange Room. The Bloc Québécois Web site featured a blog called Blogue Québécois. Other social networking sites like the microblogging site Twitter and YouTube were also prominent during this campaign. The 2008 on-line campaign was very sophisticated and dynamic; it just did not occur on Facebook.

Overall, the impact of Facebook on electoral politics remains to be seen. Even if Barack Obama wins the US presidential election, it will be difficult to assess the contributions of Facebook and other digital technologies to the victory. What is certain, however, is the growing centrality of the Internet as part of the campaign strategy in both the United States and Canada.