(Version française disponible ici)

COVID-19 was a tough stress test for Canada’s federal system of government. Our largest cities continue to suffer significant pandemic-related economic and social damage, in part due to provincial governments sweeping constitutional responsibilities they wish to avoid onto municipalities. These “creatures of the province” have become rugs provinces use to hide their problems.

COVID-19 lifted those rugs to expose a series of longstanding urban crises that provinces have offloaded onto underpowered municipalities, forcing the federal government to jump in with unprecedented direct municipal pandemic financial assistance. Anticipating future crises and acknowledging provinces’ general disdain for municipalities, the federal government should build a formal line of communication from cabinet to local government officials by, for example, re-establishing a ministry of state for urban affairs, a position that existed only briefly in the 1970s.

Any discussion of the Canadian response to COVID-19 must begin by remembering more than 52,000 Canadians died from the disease, with equity-deserving groups being the worst affected. Rapidly acquiring and distributing vaccines and implementing federal economic assistance programs for individuals and businesses undoubtedly saved countless lives. So, too, did provincial governments undertaking important public health measures such as physical distancing, mask mandates, and emergency hospital management measures to reduce infection rates.

World Health Organization COVID-19 data from G7 countries shows that Japan lost the least number of people per capita, with 59 deaths per 100,000 people. Canada lost the second least with 138 deaths per 100,000, with both countries well ahead of the United States, with 340 deaths per 100,000 residents.

I was privy to many confidential conversations about the federal and British Columbia governments’ COVID-19 response while serving as mayor of Vancouver between 2018 and 2022. The overall response from Canada was better than most. I know this from talking to mayors around the world. At international mayoral conferences I attended on Zoom early in 2020, Italian mayors wept as they described the unthinkable: their overwhelmed cities were digging mass graves to deal with the crush of COVID-19 casualties. It was horrifying.

The Canadian federal government secured critical supplies and equipment and shut borders while the B.C. provincial government implemented extraordinary public health measures to battle the virus. Physical distancing orders were essential to stop people from becoming infected, but they also changed Vancouver and other cities overnight.

Our commercial districts fell silent, economically devastating workers, businesses and, less often discussed, many municipal governments. These measures also disproportionately impacted, and continue to impact, marginalized residents – a fact that Canadians have yet to come to terms with. The worst impacted include those living with employment and housing insecurity who also often struggle with mental health and addiction challenges and tend to be racialized.

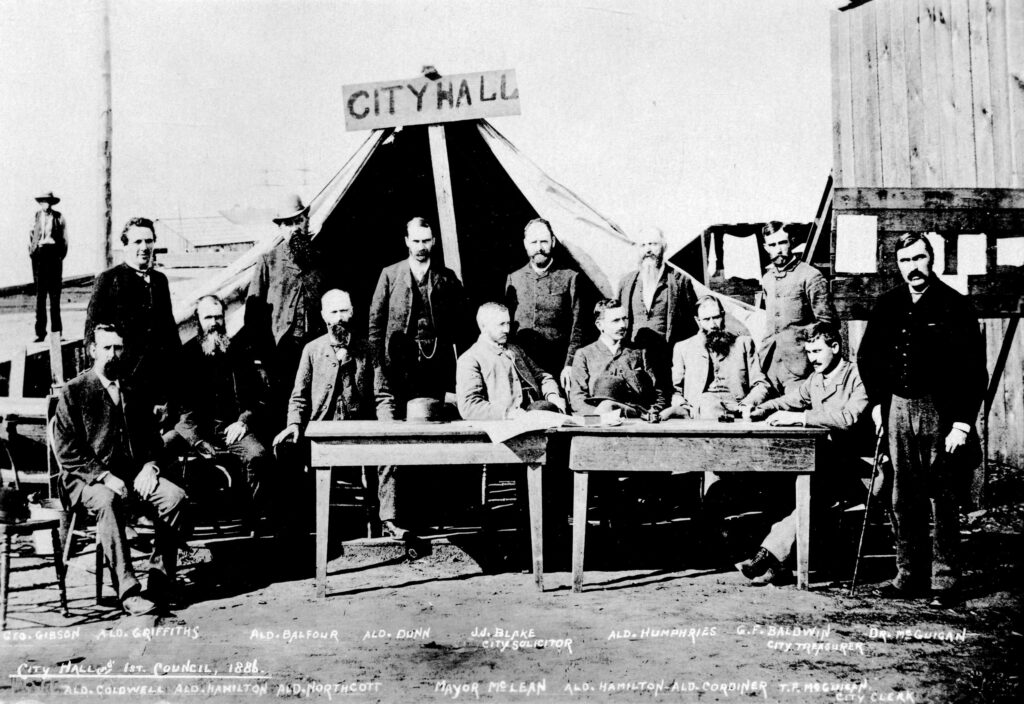

The emergency health orders early in the pandemic had an immediate economic impact on Vancouver. As businesses closed and people lost their jobs, city hall faced a dramatic decline in user fee revenues, with a projected revenue loss of $189 million for the 2020 fiscal year. We also projected a whopping 25 per cent of homeowners might only be able to pay half of their 2020 property tax bills – resulting in an additional estimated revenue loss of up to $325 million. During this early stage of the pandemic while operating under the first state of emergency in the city’s history, we faced a projected revenue loss of approximately $500 million – around 30 per cent of our total annual revenue. Without the ability to run deficits, we immediately laid off nearly 20 per cent of our 8,000 person workforce and discussed other measures such as selling city-owned land to keep the lights on during the worst disaster to hit the city since it burned to the ground in 1886.

On the social side, a large proportion of British Columbia’s social housing is in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, with approximately 160 single-room occupancy hotels providing 7,000 minimalist rooms in

which residents live by themselves and share bathrooms and other commons spaces. Many of those living in these often-dilapidated single rooms are poor, suffer from mental health and addiction challenges, are racialized, or are surviving the Canadian Indigenous genocide. These hotels permit overnight guests, which allows couples and families to stay together and means someone is nearby to provide aid to those who overdose from poisoned drugs.

Physical distancing orders forced operators of single-room occupancy hotels to cancel their overnight guest policy, which had two major negative impacts. First, hundreds of guests no longer had a place to sleep and were forced out into the streets and parks, leading to an explosion of encampments. Second, the coroner and public health officials began reporting a massive spike in illicit drug-related deaths as people began to use drugs alone in tents and back alleys as border closures disrupted the already extremely toxic drug supply. Where 248 people died from toxic drugs in Vancouver in 2019, 423 people died in 2020 – an increase of 71 per cent.

These emerging catastrophic conditions were clearly too much for municipal governments to handle on their own, especially with anti-vaxxers terrorizing health workers and protesters pushing to defund the police after George Floyd’s murder.

Thankfully, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities began to call regular Zoom meetings of the Big City Mayors’ Caucus, of which I was a member. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his cabinet colleagues frequently attended, and we had frank and open dialogues about how COVID-19 was impacting us and what needed to be done.

In stark contrast, there was little in the way of communication between municipalities and the B.C. government even though provinces are responsible for municipalities under Section 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867. It is a sad fact that I was only ever able to secure one short person-to-person call with B.C.’s then-premier Horgan during the entire pandemic.

The federal government stepped in as things worsened on the ground and for the first time in Canadian history provided direct operational funding for municipalities. Some provinces also provided funding to keep their cities and towns afloat, but only after the federal government dragged them to the table. Federal economic support programs helped people pay their property taxes and lessen the threat to this key municipal revenue source.

Stress testing Canadian governance

How to get cities out of their constitutional straitjacket

Lessons to learn from the EU and its cities during the pandemic

Let’s empower municipalities, too often the little siblings of federalism

The federal government also led the response to Vancouver encampments, with Ahmed Hussen, federal minister of housing, providing millions directly to the City of Vancouver so we could purchase hotels and erect temporary modular housing. Patty Hajdu, who was then federal health minister, increased funding to overdose response programs, including those involving safer supply.

I often wonder why Trudeau did his best to help the City of Vancouver while Horgan was content to mostly abandon us. The only explanation I can come up with is that in tough times good federal governments step up and do all they can, even when it involves wading into areas outside their constitutional responsibility, whereas provinces generally view municipalities as problems to manage rather than partners with which to work.

It is a good time for provincial politicians to reconsider how they view municipalities as we continue to sift through the COVID-19 pandemic tea leaves, although I am not hopeful this relationship will change too much as it is convenient for provinces to blame municipalities in tough times. I also think the federal government should recognize that it will have to step in again during future crises.

One suggestion to better prepare is to improve federal/municipal lines of communication – especially with the mayors of Canada’s largest cities. This was last tried under the Pierre Trudeau government in 1971, when Robert Andras was appointed Canada’s first minister of state for urban affairs. It was a short-lived appointment, abolished in 1972 because of provincial government opposition and cabinet in-fighting. However, this might be worth trying again as we collectively search for urban solutions in times of seemingly perpetual crisis.

This article is part of the Resilient Institutions: Learning from Canada’s COVID-19 Pandemic special feature series.