Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, guarantees the protection of “aboriginal and treaty rights” for the First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada. The visionaries who framed the Constitution, particularly this provision, sought to create a real commitment that Canada would work together with the Indigenous peoples. They intended that Canada would make substantial efforts for inclusion rather than confining itself to a legacy of empty rhetoric and a few words strung together in a constitutional document.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau was one of those visionaries. His son, who currently occupies the chair where PET once sat, has undertaken a discussion with Canadians about reforming our democratic system, having promised to end our current electoral system, known as first past the post (FPTP). It requires only a simple majority of votes to win a race.

Many of the great political minds advocate a proportional representation system. It would see the election of a parliament where seats are allocated to parties according to their share of the popular vote. In the FPTP system, by contrast, a party can form a majority government without actually having won the majority of votes of Canadians. This is what Justin Trudeau wants to change. He wants to introduce a system that respects the votes of the people and creates better parliaments: ones that are arguably less partisan and provide otherwise marginalized populations with a more effective role in Parliament and in government.

Here is how this could and should work, from the Indigenous perspective. New Zealand has shown itself to be bold and visionary in its electoral system. In the Maori Representation Act of 1867, it set aside four parliamentary seats for the Maori; today seven seats are designated. Members of the Maori community are not restricted to those seats: other Maori are elected to Parliament in seats other than the designated seven. And that is democracy at work. But the Maori designated seats guarantee the country’s indigenous population its voice in New Zealand’s Parliament.

Canada can be bold, visionary and progressive by doing something similar. With the national discussion now taking place on democratic reform, it is timely to consider establishing Indigenous seats in our own Parliament — effectively a form of proportional representation.

For the Inuit, guaranteed seats in the House of Commons would be a huge step forward. While the number of seats might be debatable, it would not be too much of a stretch to envisage three Inuit seats, one for the western Arctic region of Nunavut, one for the eastern region of Nunavut and one for James Bay and Labrador.

A proportionate and similar structure for the First Nations and the Métis would also be established. Candidates could be required to run as Independents, not an unusual concept since we now have Independent senators. To go a step further, the prime minister could be obliged to elevate at least one MP from each of the three Indigenous populations into cabinet.

If Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is looking for a legacy, here is his ideal opportunity. By recognizing Canada’s First Peoples in this way, he would be building on his father’s vision in 1982, which included recognition of Indigenous peoples in Canada’s constitution. He would also be cementing his place in history by bolstering his vision of rebuilding relationships and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples through significant and substantial action.

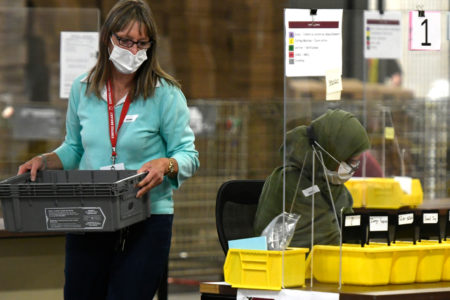

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.