Effective communication can save lives. In a crisis or emergency, it’s essential that people have access to accurate information from trusted sources to protect themselves. Yet, in our highly fragmented mediascape with its splintering of media platforms and proliferation of voices, it’s increasingly difficult to communicate risk in ways that will cut through the noise. Official public health guidance competes for our attention with news reports, public service announcements, advocacy campaigns, celebrity advice, misinformation and conspiracy theories, much of it propagated online.

Despite good intentions on the part of public officials to inform Canadians about the risks of COVID-19 and the need to protect themselves and their loved ones, rates of infection have continued to rise.

What has gone wrong with the communication campaign intended to foster compliance with public health guidelines and reduce the spread of illness?

As risk–communication scholars and professionals, and as citizens with a stake in flattening the curve, we’d like to offer our thoughts on that question, as well as what can be done to ensure communication becomes a more effective part of Canada’s ongoing pandemic response.

Coordination

The federal government runs a national department focused on health and an agency focused on public health within that department. Ten provincial and territorial governments run health ministries and those governments have divided their respective provinces and territories into numerous regional health units. Many of Canada’s more than 5,000 municipalities, meanwhile, also run their own public health departments. There are more than 1,200 hospitals, more than 2,000 long-term care homes and numerous voluntary organizations and advocacy groups in the public health arena. Many are seeking to influence our pandemic beliefs and behaviours.

However, it is the lack of coordination among them that is the real problem. Some governments describe conditions using tiers or levels (1, 2 or 3), while others use colours (red, orange, green and grey). Some jurisdictions allow gatherings outdoors of up to 10 people, others 15 or maybe it’s just five.

In some parts of the country, sending kids to school is the top priority and public health measures are designed to ensure that continues to happen. In other places, keeping gyms, restaurants and big box stores open is treated with a similar level of urgency.

For ordinary Canadians, all this noise can be frustratingly confusing. The consequences of this competitiveness and potential misalignment for vaccination uptake in the coming months could be significant.

Some governments make pronouncements about new measures that seem to involve little to no consultation with key partners. Some activities defined as “essential” in one province are deemed too risky in others, although the levels of risk are largely equivalent, and guidelines prohibiting all but essential travel and work fail to clearly identify what counts as essential. From where we sit, few of these bodies appear to be working together as they did at the outset of the pandemic when elected officials from all parties and across all levels of government spoke from essentially the same page as part of the so-called Team Canada effort.

This confusion is made worse by the myriad sources which pronounce on COVID-19 on a regular basis, from elected officials to public health leaders; CEOs of pharmaceutical companies; small business owners; scientists and academics; celebrities; and a growing army of armchair epidemiologists. These sources sometimes deliver the same message, but increasingly they are speaking across one another, competing for public attention in a risky game of one-upmanship. For ordinary Canadians, all this noise can be frustratingly confusing. The consequences of this competitiveness and potential misalignment for vaccination uptake in the coming months could be significant.

Indifference

More than 17,500 Canadians have died to date and the risks of long-haul conditions associated with COVID-19 infection are serious. So why aren’t more Canadians alarmed and focused on containing this pandemic? Part of the answer lies in communication mistakes. With few exceptions, patients with serious COVID-19 infection have been largely kept hidden from view, especially those who have passed away. People who have contracted the virus are typically referred to as “cases,” their numbers reported so often that it never really connects with ordinary people. Similarly, deaths are now reported in numbers so large that unless you have been directly impacted, no one really grasps the true severity of the pandemic.

All this information has been largely transmitted using traditional media in conventional ways (i.e., a regular, mid-day media conference broadcast on all-news television networks and then amplified across the social mediascape). While this no doubt reaches certain segments of the population, it all but ensures that younger Canadians – now the fastest-growing segment among new COVID cases – are not being reached with the information or support they need (a notable exception was a PSA by the Public Health Agency of Canada launched last summer).

Governments at all levels appear not to have effectively designed risk messaging to resonate not just with teens and young adults, but with the different linguistic, and socio–cultural communities and populations that make up our country. Those groups are more vulnerable to exposure and infection. Our system is set up well to communicate in both of Canada’s official languages but appears to be ill–equipped to communicate to Canadians in the numerous other languages they speak. This is unacceptable and all governments need to be thinking about this now.

Empathy

The American psychologist Abraham Maslow developed his hierarchy of needs to better explain what motivates people to make particular decisions. In the case of a deadly virus, we would expect people to be fully focused on the two most basic needs in the hierarchy – the physiological need to survive, and our search for security and safety. Despite what Maslow may have predicted, the need to socialize or participate in a coming-of-age ritual or family tradition (third on the hierarchy) has often won out over the need to survive the COVID-19 pandemic. This has become particularly acute as the pandemic has dragged on.

Yet for all that tension over deeply held needs, we have seen and heard little empathy on the part of our leaders. Rather, much of this communication – mostly from elected officials but also some public health leaders – has focused on instructions, warnings and scolding. Instead, why don’t they show that they know this is hard, scary and confusing? Why not approach risk mitigation and risk communication from the perspective of reducing harm rather than setting impractical standards that many tune out anyway? Why not implement enforceable policies to support survival and security so that people may be able to fulfil their need for social connection sooner and more safely? We have seen examples of empathetic public health communication over the course of the pandemic, but these are too often the exception rather than the norm.

Transparency

One of the great lessons of the 2003 SARS crisis was the importance of open communication among governments, and between elected officials and the communities they serve. An unwillingness to acknowledge and communicate urgent information about the virus in the early stages of the SARS outbreak, motivated by economic and geopolitical self-interest, aided the global spread of the disease. Only after a massive international communication effort was undertaken were chains of transmission eventually disrupted. In its final post-incident report, the World Health Organization concluded that in the case of future pandemics: “Information should be communicated in a transparent, accurate and timely manner. SARS demonstrated the need for better risk communication as a component of outbreak control.”

Although there have been significant improvements since 2003 in terms of information sharing among governments, cooperation between scientists, as well as commitments from some political leaders to be more consistent in updating the public, gestures to transparency still outweigh substantive actions by governments and health authorities alike. We don’t engage the public as a partner in pandemic response by withholding modeling data, refusing to disclose infection prevention and control benchmarks, or failing to release all advice and recommendations from publicly funded COVID-19 advisory tables. And we surely don’t engage the public as a partner by failing to align serious policy measures to the seriousness of our rhetoric.

A fresh strategy is urgently needed for pandemic communication that will capture the attention of a fatigued and disaffected public. This approach must involve a creative, coordinated campaign that features motivational messages providing realistic options to different groups that will minimize their levels of risk; credible spokespeople working in tandem across all sectors and levels of government; effective storytelling that captures public attention; and facts that appeal to logic and reason to guide informed decision-making. Information must be shared in a timely and completely open manner. If there are good reasons to withhold some pandemic planning information, then officials need to level with Canadians and explain why those decisions have been taken, unpopular as they may be.

Elected officials and public health leaders need to show Canadians with both their words and their deeds that they care and appreciate the major sacrifices we are all making – and, for goodness sake, they need to lead by example. If you’re a hospital CEO, health–care bureaucrat or elected official who wants to ignore the rules that the rest of us are also tired of following, maybe it’s time for you to step aside or be relieved of your duties.

Finally, it should go without saying that a fresh approach to communication alone won’t fix the problems that continue to knee cap our national, provincial/territorial and regional pandemic response. Better risk communication must complement meaningful policy measures that will keep people safe at home, school and work – smaller class sizes; systematic testing of asymptomatic populations; rigorous contact tracing; paid sick leave; a moratorium on evictions; a temporary ban on non-essential travel; and so on. If our health–care system is truly on the brink of collapse, as our politicians continually tell us, then they should take bolder action to show us that we are truly at a level of high urgency.

Developing a fresh campaign to flatten the curve requires money, leadership, coordination and collective commitment. It urgently demands more sophisticated communication and a more–intensive policy response than we have seen. The cost of continuing with a campaign that has been woefully underperforming will be far more significant and long-lasting.

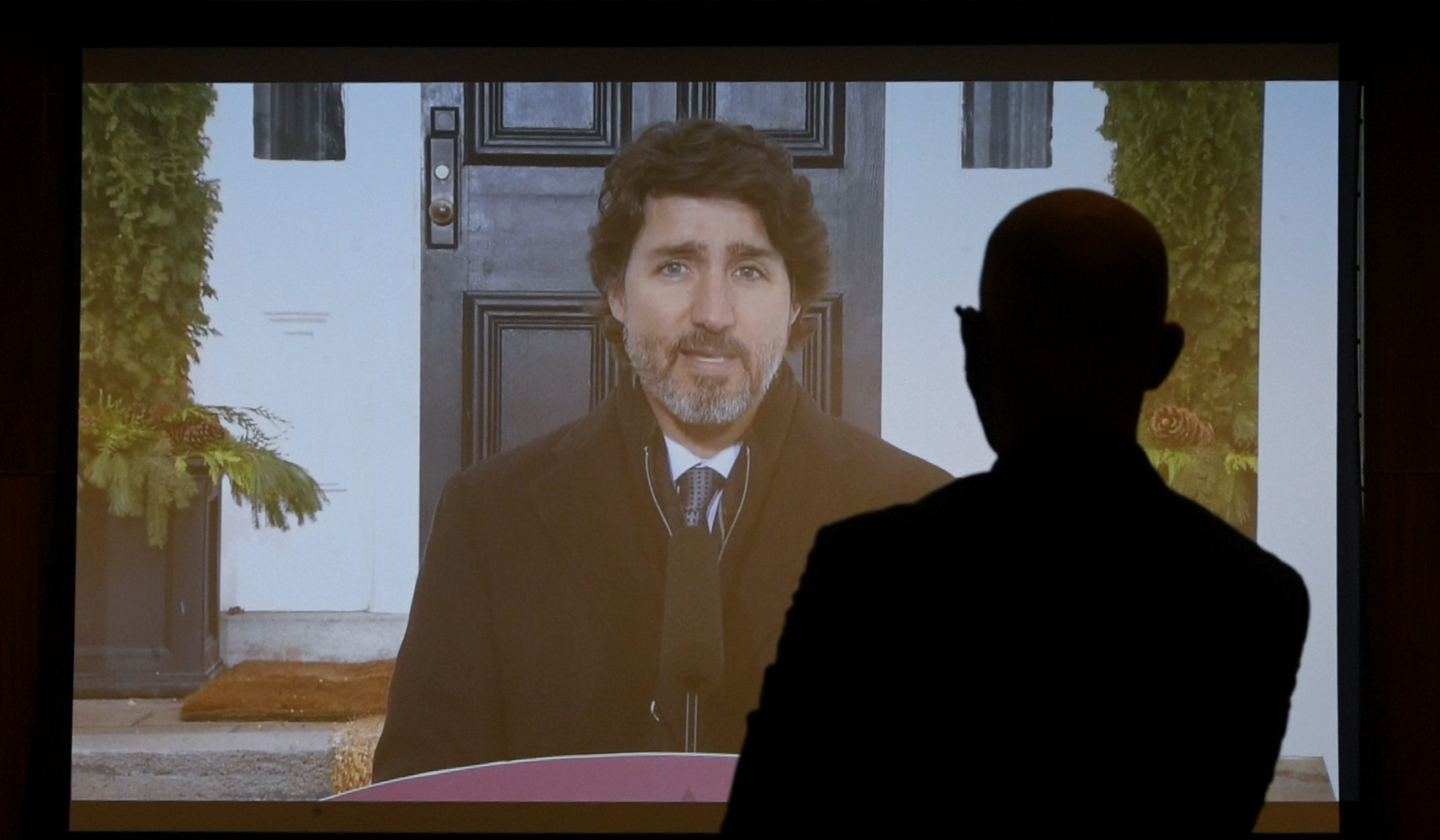

Photo: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaks during a news conference on the COVID-19 pandemic outside his residence at Rideau Cottage in Ottawa, on Jan. 26, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang