“Thanks for not tweeting about the bus,” I gratefully whispered to one of the journalists travelling with us.

“I find campaign bus metaphors so boring, so you are off the hook with me,” she said.

Our Liberal party media bus had beached itself earlier in the day like a whale, stuck on a slight incline leading into a Burnaby BC industrial park. This was Day 14 of the 2019 federal campaign.

A promising morning to launch a plank of the Liberal environmental platform had been momentarily derailed by a keystone cops farce as campaign volunteers, bemused onlookers, RCMP officers and one traumatized bus driver tried to free the immovable 20 tonne colossus by propping its suspended wheels with a combination of lumber products, rocks and elbow grease. Three journalists did a play-by-play of the incident as it unfolded.

Hello from Burnaby where the travel challenges continue for the Liberal media bus. The bus bottomed out on the way into the parking lot for Justin Trudeau’s announcement and is now firmly stuck #cdnpoli #elxn43 pic.twitter.com/uJUnMdTEXT

— Marieke Walsh (@MariekeWalsh) September 24, 2019

As the campaign’s “wagon master” for the Liberals, on a second tour of duty, I was mentally prepared for some of these logistical hiccups. Along with Terry Guillon, I was responsible for executing the movements and taking care of the media traveling with the campaign. For six weeks, we interacted with party people, reporters, photographers, local police, airport baggage handlers, restaurants, hotels and, of course, bus drivers. We were doing a different sort of media relations – any spinning we did was to make sure the wheels were spinning on time, and in the case of Burnaby, figuring out how to get them on the ground.

The media bus (or plane) is political institution, famously chronicled by Timothy Crouse’s The Boys on the Bus, or in Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail in ’72. Yet, its future remains in doubt.

Shrinking media organizations have fewer resources to afford the cost of putting a journalist on a campaign, which has traditionally can run up to $5,000 a week. Broadcasters and The Canadian Press must put multiple staff on campaigns – reporters and photographers/camera people. The number of media travelling with the national Liberal Campaign has dropped from an average of 25 reporters in 1997 to about half that in 2019.

This election had a more robust media participation than the one in 2015 – but coming into the last two federal elections, it wasn’t clear whether all three main parties would put up a media tour. The NDP, with fewer resources this election, had one bus shared by the leader and the media. Ontario Premier Doug Ford chose not to run a campaign bus during the 2018 provincial election, some speculating that his team wanted to run a safer, less scrutinized campaign. Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer’s campaign surprised many by lowering the costs it charged the media to encourage media participation. Those running the campaign hoped to generate more coverage of a lesser known leader and perhaps to distinguish it from the less-media friendly Stephen Harper era and telegraph confidence in the campaign message.

Some have questioned whether the media need to travel with the campaigns at all, what with the power of social media platforms to communicate directly with voters and the large financial expense and carbon footprint of planes and buses. Others criticize the media following the leaders for trivializing politics, engaging in pack journalism and not sufficiently covering policy. As someone who has seen the process up close, warts and all, I still think there is a value in having journalists travel with our party leaders.

Burnaby was just our latest traffic mishap. Day one of our campaign had concluded with our first bus driver plowing directly into the left wing of our campaign plane, generating a wave of media stories and mockery on social media. For the next two weeks, we would fly unbranded planes.

We were determined not to let our bus become an ongoing saga or a dreaded metaphor for a losing or disorganized campaign. Little things can add up in a campaign where margins are very close. Few people know that the 2015 Liberal media bus broke down on its first day on a stressful morning in Trenton, Ont. We were lucky to manage the situation and avoid negative momentum, which would have been very harmful to a third-place campaign.

Up until our trip to Burnaby, we had successfully kept other incidents under wraps. One morning, the leader’s bus had been rammed by a maintenance truck in a bus depot, knocking out its generator. It left a foot-long gash in its side that no one would notice the entire campaign, even as it was used as backdrop in campaign rallies.

And the day before Burnaby, we spent a half a day driving our media bus after it shed a chunk of its bumper in Stoney Creek, Ont. (Averted tweets: “Trudeau bus loses power. Pieces are literally falling off the Liberal Media Bus.”)

Part of the wagon-master responsibilities entails serving as a media advocate within a campaign to ensure journalists have enough time and space to report on the campaign. We can delay campaign events and even plane departures for media needs. There are always last-minute stragglers.

The media wagon master also works closely with the networks covering the campaign and will share details of the next day’s itinerary on a confidential basis, or what we call for “planning purposes.” This has become less necessary as satellite trucks, the main logistical media hurdle of the past, have been entirely replaced by a small technological device we carry around called a Dejero, which can feed content through cellular networks. The media bus is basically a large media filing room on wheels. It has a kitchen, printer, a couple of tables and over a dozen media workstations.

We media wagon masters are a small part of a large tour team that meticulously organizes every second of the campaign. Wonder how important it is for the leader to visit communities? Our internal polling suggested a 2-to-3 percent jump in popularity in communities Justin Trudeau would visit.

Where the front-line campaign staff tackle challenges such as international breaking news, domestic bombshells, candidate gaffes and volleys from rival leaders, we wagon masters have our own list of headaches: late candidates; under-filled rooms and disappointed organizers; over-filled rooms and fire marshals; malfunctioning or missing AV equipment; traffic jams; bus drivers trusting their gut instead of GPS; press secretaries getting themselves left behind; real protesters and fake media; and the odd overzealous local RCMP detachment.

These forces would all conspire to keep us behind schedule and imperil the most precious media bus commodity of them all, media filing time. Media have a hierarchy of needs, which includes morning coffee, wi-fi, decent food and access to a decent truck stop bathroom. Provide these things, and the media bus wagon master survives another day.

A typical campaign day starts with a policy announcement at a local venue chosen for its thematic alignment followed by a 20-25-minute-long media availability. Media filing time occurs immediately after this event – usually at a nearby hotel and under ideal circumstances lasts a couple hours.

Photographers, print and broadcast journalists use this time to do such things as set up their equipment, write and submit their content, argue with their editors, resentfully accept editorial changes to their texts and in the case of radio and TV, record and upload their stories.

Journalists will continue to work on reports throughout the day, and the TV reporters will file their on-air bits at various junctures. We had up to five broadcast reporters join us at a time – CBC, CTV, Global, Radio-Canada and TVA. The networks pool their resources to fund the presence of a producer and two camera persons/technicians, who shoot and file the raw footage for the respective newscasts and shows. How it is assembled and how the story is framed is up to the individual reporters who are writing the scripts. All of this involves setting up and taking down cameras, sound and lighting equipment, and finding a good shot in a convenient location.

Our campaign tried to maintain at least an hour for filing times for policy announcements or major stories, which is the absolute minimum needed to accommodate media needs and avoid a mutiny. And we were mostly successful. Mr. Trudeau is an energetic campaigner, doing at least six events per day.

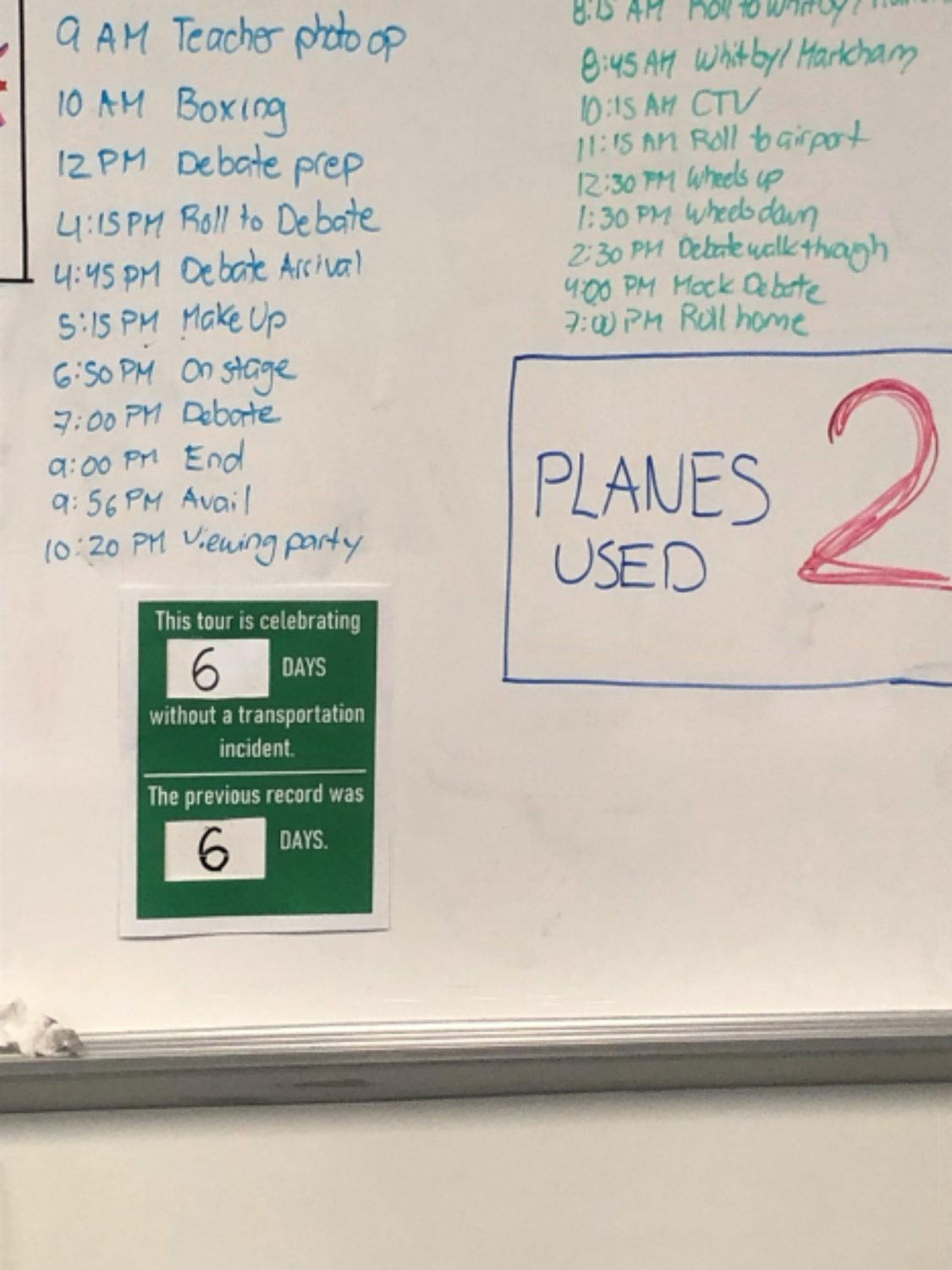

After the Burnaby event, Ottawa tour HQ created a chart tracking our days without a traffic mishap and would send us congratulations when a new record was established.

We ended up going 16 days – with our streak of luck finally broken the last Thursday night of the campaign in Montreal with a second bus beaching. The leader and media buses were being moved to provide a backdrop at the rally. The leader bus got cleanly into the event but the media bus following it somehow got stuck at the back entrance.

During the event, I snuck out to check out the bus; I could not help myself. I saw the tell-tale signs of discarded wood and rocks. The back wheels hung helplessly, cruelly elevated several inches from the pavement.

Our bus was towed to freedom as soon as the Montreal rally was over. It was dead-headed overnight to Markham, Ont., no worse for wear. We acted as if nothing had happened.

The media traveling with us were generally patient, understanding and always professional. They worked incredibly hard under tremendous pressure to tell Canadians how the election was going, keep candidates accountable and to provide local context and campaign insight to help voters make informed choices.

From my perspective, I hope the tradition of the media bus continues. It is still the best way for candidates to tell their stories, to reach Canadians where they live and to provide interaction between the leaders and the national and local media.

Some argue that campaign resources would be better served by engaging directly with Canadians through social media. Perhaps in the future we will all be replaced by artificial intelligence. Robots will be programmed not to beach their bus or drive it into airplane wings. Automated journalists will take less space and won’t complain about the quality of their vegan meals. But, until then, campaigns are still, and must be, about people. The 2019 Liberal campaign again proved the power of door knocking and personal interaction with voters. While the media bus is an imperfect institution, it still plays a valuable role connecting Canadians and their communities to the election process.

Main photo: Members of the media inspect the wing from Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau’s campaign plane after being struck by the media bus following landing in Victoria, BC, on Sept. 11, 2019. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick.

Other photos courtesy of David Rodier.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.