The TikTok “For You” feeds of Canadians are filled with the work of undeniably talented, funny and engaging creators. Producing everything from comedy sketches to makeup tutorials to social commentary, these creators put endless energy into producing high quality, professional videos.

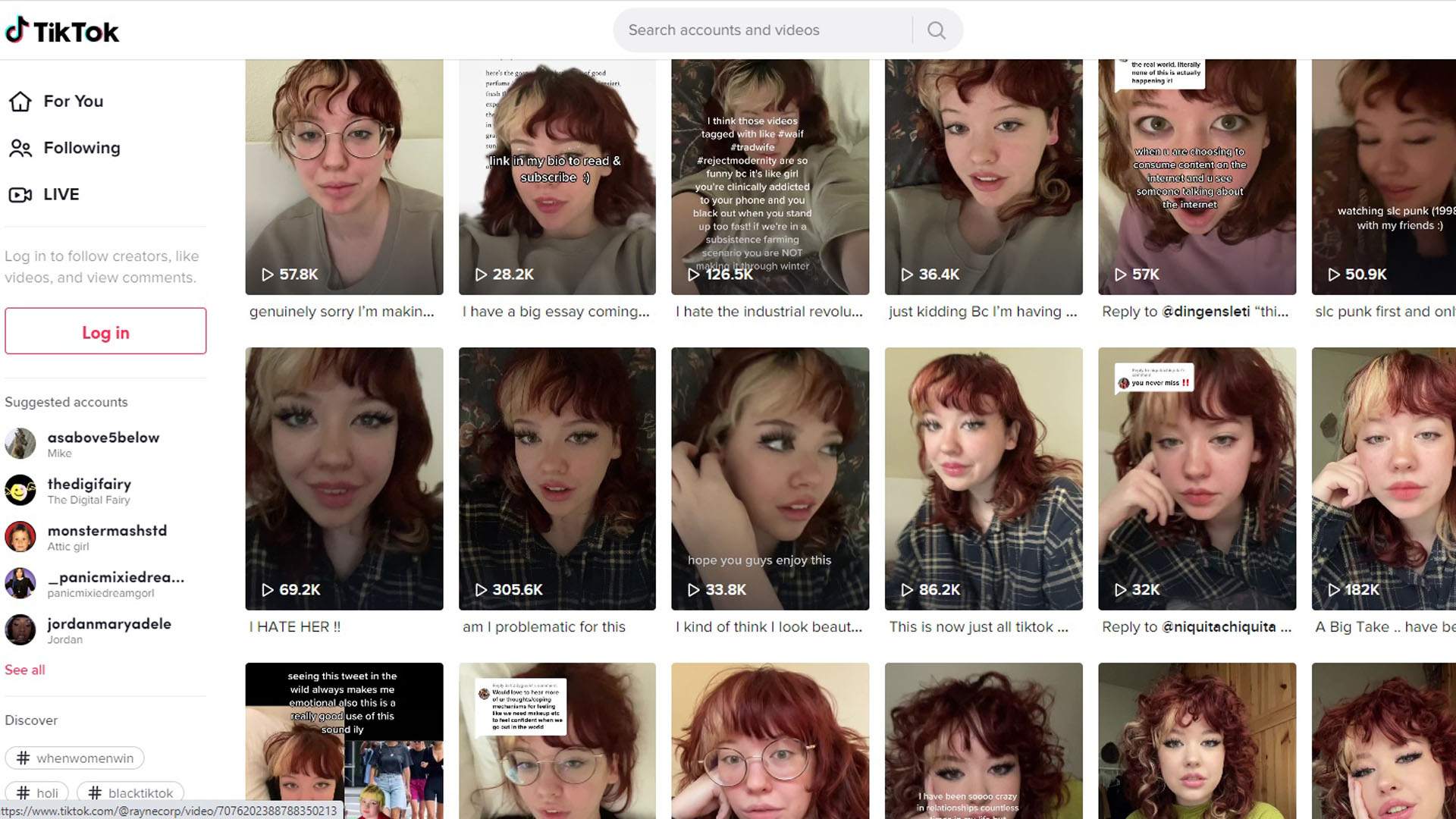

Yet without stable forms of income, many creators like Montreal-musician/comedian Eve Parker Finley or Toronto-based writer and cultural critic Rayne Fisher-Quann employ TikTok as merely one tool in their online arsenal. Visibility on the app can help promote projects with more stable returns, such as a guest video series with CBC or a Substack newsletter. While the lucky few on platforms such as YouTube might be able to make a steady living, sustained income on newer platforms remains a pipe dream.

As Bill C-11, aimed at amending the Broadcasting Act, moves through the Senate, it introduces an existential question on the nature of digital content creation in Canada. Is there a need to regulate the precarious and often exploitative industry of online content creation? This question is particularly valid if the government is willing to view digital creators on such platforms as YouTube and TikTok as distinct from traditional media creatives hosted on digital platforms.

Broadcasting renewal, broadcasting blind spots

Spearheaded by Canadian Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez, Bill C-11 is an attempt by the Liberal government to bring the Broadcasting Act of 1991 into the digital age. It primarily targets online streaming giants such as Netflix and Spotify with regards to financial contributions to Canadian content production (CanCon).

The ensuing debates over Bill C-11’s scope have raised questions about the production conditions of online creators, sometimes labelled influencers. If left out of the broadcasting system today, should online creators be given better protection in future cultural policy?

Not according to many app creators. Some of the most vocal opponents of Bill C-11 in its current form have been representatives from YouTube and TikTok Canada. Both of their written briefs to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage outline their interest in protecting digital content creation in Canada and ensuring the continued viability of the content creator career path. The assumed threat is that regulation will hurt online creators, but it is worth asking if these jobs are viable in the first place.

Online creators as cultural labourers

Across the globe, online creators struggle to succeed and profits are highly concentrated. The U.K. parliament has already conducted a consultation on influencer culture. We have not collected the same knowledge in Canada, and by comparison Canada lags behind in studying online creators, but we do have some evidence.

A significant part of creators’ work is keeping up with changes to the platforms. Though most have made themselves experts in how to optimize their content for recommendation, often through informal means, this proves to be a constantly moving target.

Content recommendation algorithms are continuously reworked. Upload schedules are punishing. The fear of lengthy gaps between posts translating into disinterest from the algorithm and eventual obscurity is a well-founded one. In short, this is a career path in an industry with no guarantee of longevity, security, or even sustained profit.

Online creators left on the outside of Broadcasting Act reforms

Is the government picking the wrong place to start regulating algorithms?

Online platforms challenge personal data protection and Canada’s cultural sovereignty

Creators do not always, or ever, get paid. Content creators are the ones who bring value to platforms such as TikTok but are not employees or even entitled to a paycheque. While TikTok’s parent company ByteDance made an estimated $58 billion in global revenue in 2021, most Canadian TikTokers were not eligible to monetize their content.

Programs such as TikTok Creator Fund, a dedicated pool of money dispersed to eligible creators based upon their monthly view counts, or the recently announced TikTok Pulse, which promises to share advertising revenue with top creators, sound exciting. However, neither is available in Canada yet.

Those creators who are able to earn money from the following they have built are either receiving donations via TikTok’s in-app currency (with a huge share withheld by TikTok as per the terms of service) or are utilized as talent for hire on the Creator Marketplace. This sub-platform connects brands with influential creators to make branded content, all within the TikTok ecosystem. In short, the economic opportunities that the company promises for creators are merely a chance to become advertisements.

Platform giants claim to be championing the small, independent creator against the tyranny of regulatory overreach. But there is a sense that they are evading regulation over the fear that forced recommendation of Canadian content will translate to algorithmic unfavourability worldwide. The result is threatening the livelihood of creators. Essentially, corporate greed and government short-sightedness are ensuring fledgling Canadian creators are caught between a rock and a hard place.

An online creators act?

When Bill C-11’s predecessor was first making the rounds in 2021, researcher Sara Bannerman wondered if regulating discoverability was the most pressing issue when dealing with digital platforms. Much of the debate now concerns what streaming platforms display on their front pages (or the carousel) yet online creators face similar challenges to being discovered.

Some creators worry that their sexuality or body type might disadvantage them. How might an online creators act unmask some of the gendered and racial biases that could be built into such algorithms and allow marginalized creators to thrive?

Going even further, what might a system where digital platforms offer actual financial equity for creators look like? This is not something that would be willingly given by these corporations. More likely, it would require creators to undertake meaningful labour organizing. Ensuring basics such as a guaranteed minimum wage for sponsored content or benefits like health insurance is possible if digital creators wield the power of collective bargaining.

Digital creators have already had some success. Podcasters at Spotify have formed a union. YouTubers, working with management company Standard, used the strength of their creator collective to negotiate better rates for sponsorships. They are also carving a path to equity with their creator-owned streaming service Nebula. Some TikTok creators now work together to share attention. Yet these efforts pit precarious creators against some of the best-funded firms in media.

If Canadians truly wish to grow our digital-first creative industries, the legislation needs to support and give creators new rights. The federal government could support these efforts with legislation. Along the lines of something like Canada’s Online News Act, new legislation could grant creators powers for collective bargaining. Forcing arbitration, given the power asymmetries between many sellers and the few buyers, may help. Also key: supporting more independent creators (something the proposed Online News Act may struggle to do).

Bill C-11 might succeed only by sidestepping the difficult, less understood problems facing Canadian creators. Another act should follow. Canadian creators have so much to offer audiences both at home and globally; it’s time to make sure they are actually compensated for this work.