On Thursday, July 20, Appeal Court Judge Michael Dambrot ordered a new trial for Mustafa Ururyar, who Judge (retired) Marvin Zuker had found guilty of sexual assault of Mandi Gray (she has waived the traditional ban on publication of her name). Ururyar’s defence appealed the verdict on the grounds that the trial Judge was biased.

In his reasons for judgment on July 21, 2016, Zuker addressed many rape myths that had been used by the defence. Regarding myths about physical injury, Zuker wrote: “The absence of injuries might suggest that the victim failed to resist and, therefore, must have consented. The fact that a victim ceased resistance to the assault for fear of greater harm or chose not to resist at all does not mean that the victim gave consent.”

Despite the experience being so common, sexual assault is widely misunderstood. Many people still hold firmly to ancient “rape myths”; for example, rape happens when a dangerous-looking stranger suddenly and violently attacks a woman who fights him to the point of injury, but is overpowered. She immediately seeks help as soon as she can escape and never has further contact with him.

Questions that are routinely asked in sexual assault trial cross-examinations of victim witnesses are based on rape myths. They are based on a presumption that if there was a relationship between the accused and the victim (versus they were strangers), there was a lack of physical injury (versus there was injury), the ordinariness or likability of the accused (versus the accused was dangerous), it is unlikely that there was a sexual assault. Instead, it is argued, a judge should find that there is no evidence for lack of consent.

Why the reasoning is illogical

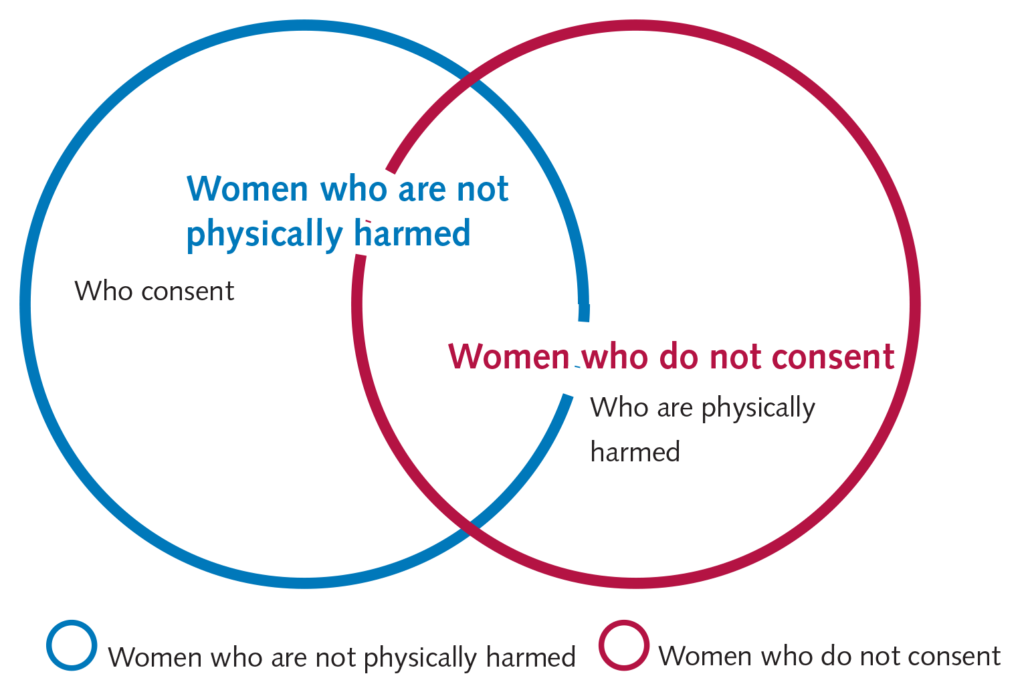

The reasoning behind the questions is illogical, but because the myths are widely held, it is difficult to recognize the false reasoning. Maybe this graphic will help demonstrate the problem in the reasoning, using physical injury as an example.

The blue circle represents women who are not physically injured. The red circle represents women who did not consent. If the myth was true that victims are always physically injured, the circle representing the state of being “not physically harmed” would not overlap with the circle representing the state of “did not consent,” because a sexual assault would, by definition, involve physical injury. But we know, factually, that most women who do not consent are not physically injured: they were sexually assaulted. The circle representing the state of being “not physically injured” must overlap with the circle representing “did not consent.” We can call the part where the circles overlap “the lens”.

Here’s the concept in words:

All women who are physically injured are also women who did not consent to sex.

All women who consent to sex are also women who are not physically injured.

Some women who are not physically injured are also women who did not consent to sex.

Some women who did not consent are also women who are not physically injured.

What the defence asked Judge Zuker to believe is that because “there were no confirmatory injuries,” there is reason to believe that there was consent, as if all women who are not physically injured consent to sex. But that is not one of the four logical possibilities, because the circles are known to overlap. The two statements above, about “some women,” pertain to the lens-shaped area where the circles overlap. If a woman is not harmed, her situation may have been either in the “consent” part of the “not harmed” circle or in the lens-shaped part where it overlaps the “did not consent” circle.

A woman’s lack of physical injury thus cannot inform any logical inference about whether or not she consented, and thus there is no reason for a defence lawyer to draw attention to it. To put it bluntly: if she was physically injured, it’s a near certainty it was sexual assault. If she wasn’t, we don’t have any evidence, either way. The words “physically injured” can be replaced with “tried to escape,” “screamed,” “immediately reported,” or multiple other rape-myth-based content.

As Zuker’s detailed reasons for judgment outlined, Ururyar’s defence consisted of little other than rape myths. Zuker wrote: “I must and do reject his evidence.” In contrast, Zuker accepted the clear, consistent testimony from Mandi Gray about Ururyar’s verbal and then sexual aggression against her on the night in question.

It is high time that we move into the modern era with our thinking about what to believe in sexual assault trials. As Judge Dambrot said at the appeal hearing, in March 2017: “Judges judge. They should do it right.” Perhaps “doing it right” includes thinking logically. To call a rape myth what it is, is not evidence of bias. Dambrot’s ruling should be challenged.

Photo: Toronto, April 3, 2011 – Slutwalk protesters gather to raise awareness about victim blaming and rape myths, by Anton Bielousov.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.