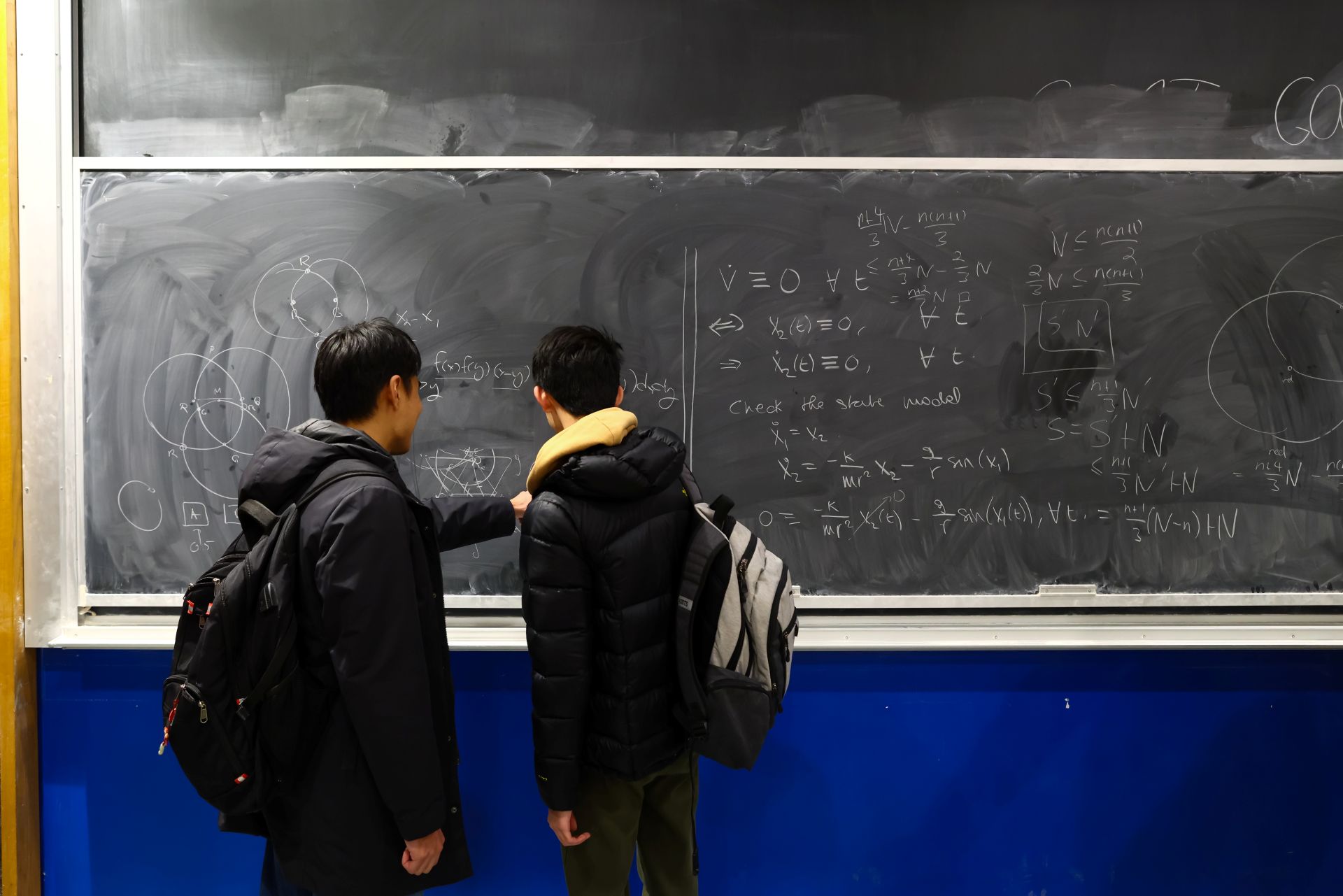

As a PhD student and teaching assistant, I do not need a government report to understand the impact of artificial intelligence on post-secondary education. I see it every week.

Students are already using these tools to study, debug code, draft essays and unpack complex proofs. Yet, the response from the education system has been chaotic. While Ottawa launches a high-level task force and other consultations, the actual classroom experience has devolved into a patchwork of confusion, symbolic bans and widening inequality.

Canada is letting the transformation of education happen by accident. By failing to adopt a coherent, system-wide approach, governments and institutions are leaving individual instructors to improvise – and students are getting caught in the middle.

Although education is a provincial responsibility, there are three things the federal government can do: call meetings with the provinces to develop a pan-Canadian approach; provide the necessary funding to meet the challenge and treat AI as what it already is – a fundamental part of national infrastructure.

The geography of confusion

Without such action, post-secondary institutions have been left to navigate this disruption largely on their own. The result is contradictory guidance that changes not just from province to province, but from course to course.

Consider the mixed signals a Canadian student faces today. At the Université de Montréal, early guidance reflected a ban-first approach, forbidding ChatGPT unless explicitly permitted. Queen’s University, by contrast, chose not to ban tools outright, asking instructors to set their own rules.

At the University of British Columbia, usage is treated as potential misconduct unless the syllabus says otherwise, while the University of Alberta relies on broad principles that ultimately defer to course-level agreements.

This lack of consistency leaves students uncertain about what is permitted.

Worse, it pushes departments toward symbolic control – banning tools that students freely use at home or leaning on AI-detection software. These detectors are increasingly recognized as unreliable and prone to false positives, particularly against non-native English writers, as shown in a recent study. Yet in the absence of better options, they remain a crutch.

Three fractures in the system

This policy vacuum is not just an administrative headache. It is creating structural fractures in Canadian education in several ways:

Assessment is broken: Traditional take-home essays and problem sets were not designed for a world where polished writing or code can be generated in seconds. Yet, recent data from the Future Skills Centre and the Conference Board of Canada – How Are Educators Navigating the AI Revolution? – found about 80 per cent of educators report having little or no training on how to integrate generative AI into their teaching.

Without support, many are retreating to in-person exams rather than redesigning assessments to evaluate the process of learning instead of just the final product. As a TA, I have seen how in-person exams can raise student stress, push learning toward short-term recall and take away class time.

The “AI divide” is widening inequality: Post-secondary education is rapidly becoming a two-tiered system. Students with newer hardware, stable broadband and paid subscriptions to premium AI models have a clear advantage over those relying on restricted free tiers or no access at all.

Premium features can make AI assistance more accurate and more usable at scale, potentially boosting outcomes for students who can afford them while others lag behind.

Generative AI and deeper thinking: What’s in our heads still matters

This emerging AI divide mirrors existing socioeconomic gaps. As the OECD has warned, without deliberate intervention, access to AI is likely to follow patterns of income and geography, widening disparities in learning opportunities. If access to powerful learning assistants is determined by a student’s ability to pay, AI risks becoming a driver of inequality rather than a tool for empowerment.

The skills gap is being ignored: While federal digital strategies – including its Guide on the use of generative artificial intelligence – emphasize the need for Canadians to critically evaluate AI, curricula are slow to adapt.

Schools and universities are failing to teach the AI-era skills that actually matter, such as designing prompts, spotting hallucinations, interrogating sources and explaining reasoning rather than simply repeating answers.

A realistic path forward

Canada cannot wait for a perfect consensus. It needs a pragmatic strategy that respects federalism while addressing these fractures. Here are three action items:

First, Ottawa must use its convening power. While the federal government cannot dictate curricula, it can work through the Council of Ministers of Education to establish a pan-Canadian framework. That framework should set baseline expectations for ethical AI use, disclosure in coursework and data privacy in education.

Second, the transition must be funded. Telling educators to innovate without support is a recipe for burnout. The federal government should provide targeted transfers to fund interinstitutional pilots and professional development. The system needs shared repositories of AI-aware assignments and rubrics, not just high-level policy papers.

Finally, AI has to be treated as infrastructure. To prevent inequality, school boards and institutions should use shared procurement agreements to provide equitable access to safe, vetted AI tools. That would reduce vendor lockin and ensure that student data is subject to public oversight rather than private terms of service.

The federal AI Strategy Task Force has been asking Canadians to help define the country’s future. Education must be at the centre of that conversation. The question is no longer whether to embrace or resist AI, but whether educators and policymakers will shape its role in classrooms – or allow it to reshape learning without them. Canada cannot afford to drift.