At Parc Lefebvre in Montreal’s LaSalle borough, I watched strangers turn into neighbours around a set of outdoor ping-pong tables. It’s a modest project, chosen and funded by residents through a process called participatory budgeting, but the social dividends are anything but small. Similar resident-selected projects have since popped up across LaSalle, from community gardens to a winter snowpark, because thousands of people raised their hands not just to be consulted, but to decide.

At a time when trust in public institutions is fragile and many residents feel disconnected from local decision-making, participatory budgeting offers something concrete: visible influence over real public dollars. Done well, it strengthens democracy. Based on what I’ve seen in LaSalle, and on evidence from Canada and abroad, there are a handful of design choices that determine whether participatory budgeting builds trust, broadens participation, and delivers results people can actually see and use.

What participatory budgeting can and can’t do

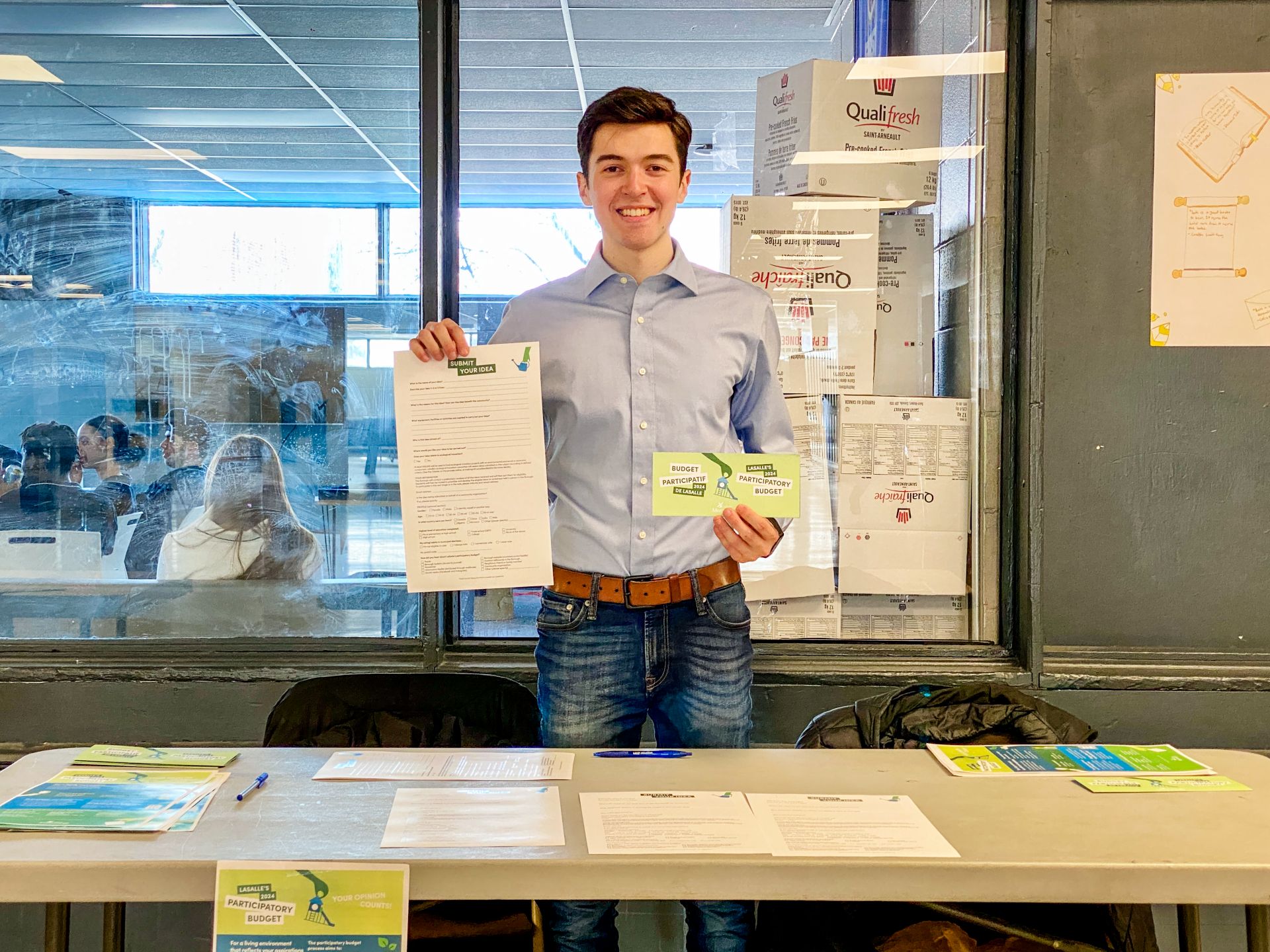

Since 2021, I’ve served on the steering committee for LaSalle’s participatory budget through its three editions, helping shape its rules, outreach, and project evaluation. Each cycle deepened my appreciation for how local democracy can work when residents are trusted to lead, and how even modest sums can transform public trust into visible results.

Here’s how participatory budgeting works: governments set aside a real slice of funds; residents propose ideas; staff and resident delegates refine them; everyone votes; and the winning projects get built. It’s democratic muscle memory for communities that want more than a public hearing.

Of course, participatory budgeting can’t solve every policy issue, and it’s not meant to. Instead, it complements representative democracy by giving residents a direct hand in shaping the places they call home. And, as the evidence shows, when people can see their priorities reflected in real projects, trust and well-being both improve.

Participatory budgeting can increase public trust and perceptions of government transparency and accountability, strengthening the relationship between residents and decision-makers.

Participatory budgeting is proving itself

Montreal recently completed its third citywide participatory budget. More than 880 ideas were submitted, a record 28,000+ ballots were cast, seven projects were selected, and $45 million was invested, including at least $10 million reserved for youth-focused projects.

The city’s model has matured and scaled, with nearly 20 winning projects since the first edition in 2020, roughly $101.5 million directed across its three rounds, and participation now totalling in the tens of thousands.

Canada has many proof points for participatory budgeting.

Vancouver’s first participatory budget in its West End neighbourhood drew more than 8,600 participants to allocate $100,000. Victoria’s 2021 participatory budget allocated just over $54,000 to six initiatives and the city continues to award micro-grants to resident-led projects. Toronto Community Housing entrusts tenants with millions annually for improvements, an approach that demonstrates scale and meaningful control over the built environment.

The international evidence backing participatory budgeting is striking: Brazilian municipalities that adopted it saw a measurable drop in infant mortality – on the order of five-to-10 per cent – alongside shifts in spending toward basic services.

Closer to home, it is also a recruitment tool for democracy: participation rules often allow voting from age 12 and processes are designed to include renters, newcomers, and non-citizens – people who don’t always feel invited into formal public decision-making. Some research also links participatory budgeting to higher local tax compliance over time, a plausible outcome when residents can see their priorities turning into projects.

The challenges

Participatory budgeting is not without shortcomings. Pilots fizzle when they’re too small to matter or when political support fades. For instance, Hamilton’s Ward 2 saw participation drop between its first and second participatory budgets, after which the program was discontinued. Larger administrations also struggle to keep processes inclusive as they scale because the work of translation, facilitation, and outreach is demanding. Under-resourcing that work undercuts the promise. But these are design problems, not fatal flaws.

As someone who helped steer LaSalle’s participatory budget process, there are a few essential design choices I recommend to Canadian municipalities and community leaders who want participatory budgeting to thrive, from Toronto and Montreal to mid-sized cities and small towns.

Put real money on the table.

Residents know the difference between a contest and a commitment. Aim for at least one per cent of the capital budget (more in large cities), with a multi-year runway so projects can be scoped, built, and celebrated. Montreal’s third year of participatory budgeting shows what happens when scale increases: record participation and a citywide slate of seven winners that enhanced public spaces, greened the city, and improved community amenities.

Lower the barriers, especially for youth.

Let residents vote from age 12, accept more than one way to prove a local connection (residence, work, study), and meet people where they are: schools, libraries, arenas, transit nodes. Montreal and other Canadian municipalities already do this. In LaSalle, youth-friendly voting and simple forms lifted participation and surfaced projects of real interest to teens. Research shows that the earlier young people start practicing democratic participation, the more likely they are to stay engaged throughout their lives.

Blend online with on-the-ground presence.

Digital tools widen reach while assemblies and kiosks build trust. The strongest Canadian cycles pair accessible platforms with staffed, multilingual outreach and hands-on workshops to co-design feasible proposals.

Follow through and show your work.

Publish implementation dashboards, set service-level targets, and budget for contingencies so projects don’t die on the vine. Montreal provides project-level updates and open data. That visibility keeps residents engaged from ballot to ribbon-cutting.

A lever for equity

Participatory budgeting can help rebalance who gets heard, which is particularly useful for cities thatstruggle with uneven access to safe parks, transit amenities or community facilities. Last year, for example, Montreal reserved a major tranche for youth-oriented solutions, while other winning projects focused on accessible public washrooms across multiple boroughs, improving dignity and public health through small but meaningful infrastructure.

Across Canada, cities have shown that relatively modest participatory budgeting envelopes can activate thousands of residents. Vancouver proved how quickly people engage when they can directly shape local improvements. Victoria demonstrated that small rounds can build habits and community capacity. And Montreal shows that scaling the pot scales the civic energy, translating public input into safer, greener, and more welcoming neighbourhoods.

In an era of strained trust, giving residents a meaningful say over public spending helps build a democracy that people can feel under their feet.