(Version française disponible ici)

The Trump administration’s recent assertion that Tylenol (acetaminophen) use during pregnancy may cause autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has sparked intense controversy – not only for its lack of scientific credibility but also for the communication challenges it poses to pharmaceutical companies, medical professionals and public health officials.

Billed by President Donald Trump as “one of the biggest [medical] announcements…in the history of our country,” the administration’s claim was not based on quantitative meta-analysis or scientific consensus – as one should expect in such cases – but on a selective reading of observational studies suggesting the possibility of a correlation.

Unsurprisingly, the administration’s statement has sown confusion and anxiety among expectant parents and triggered a potential reputational crisis for Tylenol and its parent company Kenvue.

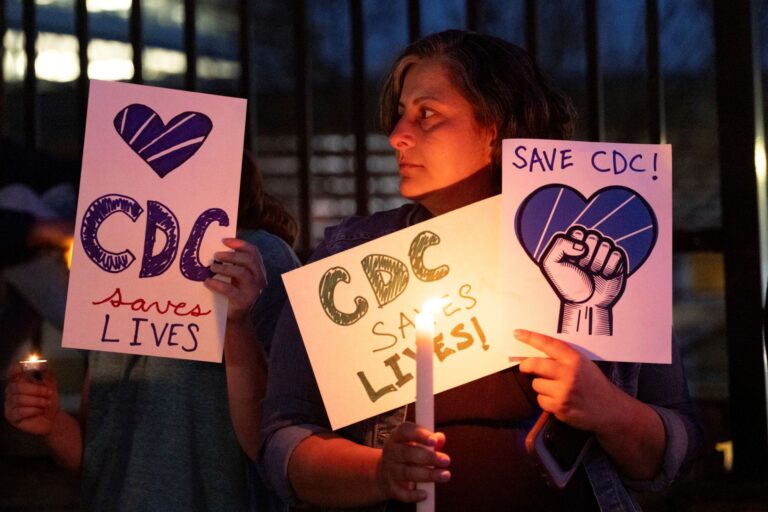

But the damage goes beyond corporate public relations. This episode reveals a deeper dilemma: the growing threat of misinformation and erosion of public trust in institutions. It poses a risk to public health that can be mitigated with rapid, collaborative response, accurate information, and holding those responsible to account.

Tylenol has weathered crises before. In 1982, seven people in the Chicago area died after ingesting cyanide-laced capsules. Johnson & Johnson, the brand’s then-owner, responded decisively, pulling 30 million bottles from shelves, halting advertising and leading the charge for packaging reforms. That incident had a clear cause and solution, and the company’s response is still considered a gold standard in crisis management.

From cyanide to misinformation

Today’s crisis is more complex. It stems not from product tampering but from politically weaponized misinformation. The media environment is fragmented. People get information not just from subject experts via journalists but from influencers and algorithms. Trust in institutions has been weakening for decades and grievance culture is on the rise.

Kenvue responded swiftly, reaffirming that “independent, sound science clearly shows that taking acetaminophen does not cause autism” and warning against discouraging its use during pregnancy because alternatives such as ibuprofen carry known risks. While its share price is stable, the social fallout may be harder to contain.

Medical experts have condemned the administration’s statement. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists called it “highly concerning” and “irresponsible,” emphasizing that untreated pain and fever during pregnancy can pose serious risks to both mother and fetus. The Autism Society of America criticized the claim as “unfounded,” warning it distracts from efforts to support people with ASD and their families.

The erosion of public trust

This episode reflects a broader crisis: the growing influence of health misinformation. A recent Canadian Medical Association survey found that Canadians are exposed to significant amounts of health misinformation.

Those who spend more time on social media are more vulnerable to its negative effects such as delayed medical treatment, strained relationships and heightened anxiety. The erosion of trust in governments, legacy media and public institutions has created fertile ground for misinformation to flourish.

Why academics must speak out against Trump and disinformation

Social media platforms amplify the problem. Their algorithms prioritize engagement over accuracy, allowing false claims to spread faster than corrections. As the saying goes, “a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.”

A study in Health Promotional International identified social media-based misinformation as a major threat to public health, calling for strategies that include monitoring, debunking, education and systemic regulation.

Six steps to counter health misinformation

The Tylenol-autism claim is a textbook case of how misinformation undermines evidence-based medicine and endangers public health. It weaponizes uncertainty, exploits emotional vulnerability and bypasses traditional scientific gatekeepers – jeopardizing individual health decisions and weakening our collective capacity to respond to real threats.

So, what can be done?

- Rapid Response: companies such as Kenvue must continue issuing clear, evidence-based messaging. Ongoing engagement, particularly on social media, is essential to counter misinformation.

- Collaboration: this isn’t just Kenvue’s problem. It affects the whole medical and public health ecosystem. Unified messaging from trusted brands can help restore public understanding and trust.

- Partnerships: Kenvue should work with advocacy groups supporting people with autism and their families, and those in the maternal health sector, to put a human face to the issue and provide credible voices to counter fear-based narratives.

- Media literacy: governments need to invest more extensively in initiatives that empower individuals to accurately assess health information, including educational content, school curricula and community outreach.

- Regulatory oversight: governments should use available tools to hold social media platforms accountable for spreading health misinformation. Measures such as warning labels, content moderation and algorithmic transparency are vital.

- Support for frontline workers: physicians and nurses need resources to address misinformation in clinical settings, while public health officers must stay informed about the evolving media landscape and its impact on health misinformation.

The Trump administration’s claims about Tylenol have created a public relations nightmare. But more importantly, they reflect a deeper malaise. In an era where falsehoods spread faster than facts, the challenge is not just correcting misinformation but rebuilding public trust. That requires co-ordinated action, sustained investment and renewed commitments to science-informed communication.

Failing to meet this moment risks not only institutional credibility but the health of future generations.