Across Canada, debates about diversity have been subsumed by the “anti-woke” backlash. The term “woke” — once a call to remain alert to injustice — has been stripped of its historical meaning and used instead to cast diversity as a liability. In this climate, diversity is often misrepresented as a threat to academic excellence, democratic stability and economic prosperity.

Yet, evidence from across disciplines demonstrates the opposite. When cultivated thoughtfully, diversity expands perspectives for solving complex problems; strengthens dialogue across difference; and bolsters democracy against authoritarian drift.

This is not a time for retreat. Universities, civil society and policymakers must pursue a twin imperative of democratic fortitude (the courage to defend democratic life) and democratic regeneration. We need to renew civic life through what I call the pluralism dividend — the social, democratic, and civic benefits that emerge when diversity is cultivated through inclusive institutions, participatory governance and structured engagement across differences.

For decades, “social cohesion” was the dominant template for managing diversity in western cultures. But while emphasizing harmony and stability, it also carried assimilationist undertones, glossed over structural inequalities and treated difference as a problem to be smoothed away.

In today’s polarized era, cohesion is no longer enough. We need a bolder vision — pluralism, belonging and solidarity — that not only accommodates diversity but cultivates it. The pluralism dividend manifests stronger social trust, reduced polarization, equitable participation and stronger democratic norms.

Super-diverse and hyper-diverse societies

Canada’s cities and universities are super-diverse and hyper-diverse laboratories that reflect the complexity of demographic diversity.

Super-diversity is a term coined by sociologist Steven Vertovec to capture variations within migration histories, socio-economic status, religion and transnational ties. Hyper-diversity gets beyond older frameworks like multiculturalism and highlights the intensity of demographic differences — ethnicity, language, religion, gender, migration status and socio-economic background.

While super-diversity focuses on the complexity of migration-related diversity, including the intersections of demographic and legal statuses, hyper-diversity expands the focus to lifestyles, attitudes, values, behaviours, and practices.

Both terms underscore the reality that social trust, belonging and social solidarity can erode without intentional engagement.

Public perceptions of immigration demonstrate this fragility. In 2022, seven in 10 Canadians supported the country’s immigration levels, the highest such reading in 45 years of surveys. But by 2024 — driven by concerns over affordable housing and public services — nearly six in 10 said Canada admits “too much immigration.” This lurch in perceptions shows the need for policies and programs that cultivate democratic capacity and the pluralism dividend.

How we can use policy to achieve the pluralism dividend

Cultivating the pluralism dividend requires deliberate action, particularly in three critical areas.

- Universities must embed pluralism into curriculums, research, campus programs and civic outreach, advancing epistemic freedom and cognitive justice by engaging Indigenous, diasporic and global South knowledges into problem solving.

- Cities need to function as laboratories of pluralism. Including immigrant and minority populations in planning discussions, service design and participatory governance is a key strategy for building civic belonging and reducing community fragmentation.

- Community organizations should foster cross-community collaboration, leadership and civic ownership. Pursuing partnerships with universities and governments not only helps communities access more opportunities, but helps them shape policies that positively affect their futures.

These steps all represent a shift from managerial approaches to stewardship of dialogue, trust and knowledge co-creation — the conditions that allow pluralism to flourish.

Civic laboratories: Calgary, Toronto, Halifax, and Winnipeg

Canada’s cities are excellent testing grounds for pluralism, illustrating both the challenges and opportunities of super-diversity.

In Calgary, 41 per cent of residents are immigrants, speaking more than 180 languages. Organizations such as ActionDignity, DiverseCities and Immigrant Services Calgary channel this complexity into civic capacity — improving access, combating inequities, fostering leadership, facilitating employment and supporting settlement.

In Toronto more than 46 per cent of residents are foreign-born, representing over 200 ethnic groups and more than 160 languages. Neighbourhoods like Thorncliffe Park and Rexdale illustrate both the challenges of layered difference and the potential for participatory engagement. Local initiatives such as the Black Creek Community Farm and Scarborough’s Neighbourhood Improvement Areas foster a sense of belonging, involving residents in planning initiatives on issues like housing or employment opportunities.

Halifax’s Peace by Chocolate and Winnipeg Chaeban Ice Cream leverage the pluralism dividend. Founded by refugees, both enterprises generate economic value, intercultural exchange and civic participation. They recognize newcomers as contributors of social, cultural and economic capital, not simply individuals to be integrated.

Super-diversity means that we often do not know one another. Programs that engage people across our differences, through dialogue and civic participation, cultivate trust and democratic engagement. Calgary, Toronto, Halifax and Winnipeg show how pluralism produces measurable benefits when intentionally stewarded.

When super-diverse populations are meaningfully engaged, collaboration and social trust deepen, and the pluralism dividend is realized.

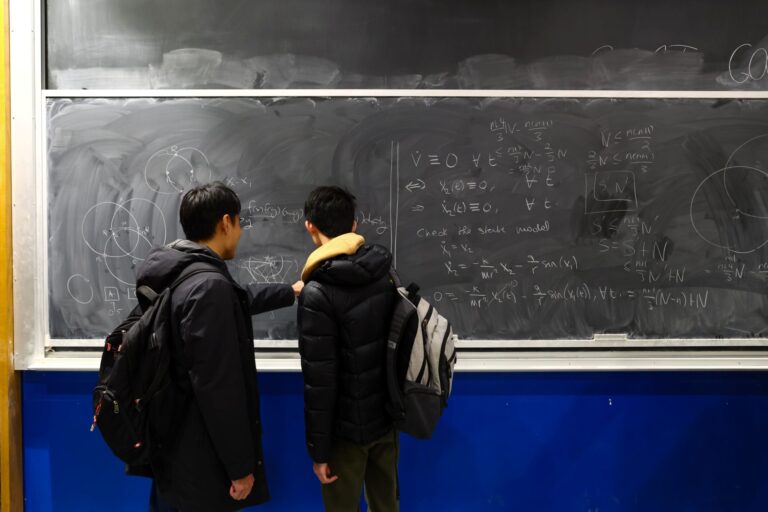

Universities as engines of the pluralism dividend

Universities are central to this transition. They connect students, faculty and researchers with surrounding communities, sharing academic assets for application in civic life. Classrooms, research labs and civic-engagement initiatives are often where residents learn to navigate difference, deliberate collectively, and co-create solutions — vital in helping local programs succeed in super-diverse cities.

Research confirms the democratic value of diversity. Harvard social scientist Robert D. Putnam’s work on social solidarity and social capital demonstrates that while super-diversity can lead people to “hunker down” — withdrawing from strangers and even neighbours — long-term analysis shows that with inclusive institutions, diverse communities build new forms of solidarity and trust.

Diversity researcher Scott E. Page makes this concrete. In The Difference, he shows that cognitively diverse groups — those with varied perspectives and problem-solving strategies — outperform homogeneous groups of “like-minded experts” when confronting complex problems. In The Diversity Bonus, Page demonstrates how demographic diversity correlates with cognitive diversity, producing gains in innovation, predictive accuracy and organizational performance.

Likewise, Canadian researchers Bessma Momani and Jillian Stirk found that intentionally cultivating diversity produces a significant “diversity dividend”. Societies and organizations that embrace inclusion achieve stronger economic performance, institutional adaptability, cultural competency, and global credibility.

These findings reinforce how universities, by sustaining inclusive learning environments, directly strengthen Canada’s civic and democratic regeneration.

Epistemic freedom, cognitive justice and pluriversality

Universities convert demographic complexity into civic strength when they embrace epistemic freedom, cognitive justice and pluriversality.

Historian Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni defines epistemic freedom as enabling marginalized communities to think, theorize and produce knowledge based on their own histories, worldviews, lived realities and cultural resources rather than solely within Eurocentric frameworks. This ensures multiple sources of knowledge can flourish without being subordinate to any single hierarchy.

Cognitive justice, according to international scholar Catherine Odora Hoppers, is the principle that all knowledge systems have the right to coexist, interact and contribute to solving shared challenges. Thus, epistemic freedom and cognitive justice challenge the monoculture of Western modernity by recognizing plural knowledge systems — including Indigenous, African and diasporic knowledges — as indispensable contributors to policy, governance and social transformation.

Researchers such as Walter Mignolo (on pluriversality and multipolarity) and Arturo Escobar (Designs for the Pluriverse) propose pluriversality as an alternative to conventional claims of a single worldview. Unlike relativism, pluriversality fosters an ecology of knowledges in which diverse traditions interact without assimilation. This requires a commitment to relationality, recognizing that no knowledge system is complete in itself; all knowledge is interdependent. This knowledge pluralism lets universities mediate polarized worldviews, social inequality and democratic backsliding by drawing on the widest possible range of intellectual and cultural resources.

Together, these principles — epistemic freedom cognitive justice, and pluriversality — have practical application for understanding diversity and diverse worldviews. They make diversity not only a source of shared belonging and solidarity, but also of social innovation and democratic renewal. They help students appreciate difference and recognize epistemic multiplicity as essential to social life in a super-diverse world, directly countering the risks of polarization, inequality and the erosion of democratic norms.

Stewardship, pluralism, and democratic capacity

The pluralism dividend positions Canada as a global example of how actively cultivated diversity strengthens democracy, mitigates polarization and enhances social and economic well-being.

Canada’s opportunity lies not in treating diversity as a liability but cultivating it as a foundation for democratic strengths. Advancing pluriversality can ensure that pluralism becomes a lasting source of belonging, solidarity and democratic renewal.

Canada’s universities are positioned to lead and energize this transition. By connecting demographic complexity to epistemic plurality and civic engagement, they transform super-diverse populations into engaged citizens and innovators in democracy. In an era of polarization and democratic backsliding, this is central to the mission of higher education and to the future of democracy, itself.

Policymakers, educators and civic leaders must seize this moment. When cultivated with courage and imagination, super-diversity becomes the foundation of both an inclusive university and society.