The efficiency and reliability of a country’s transportation networks are key drivers of international competitiveness, and can help expand global trade and attract foreign investment. This is particularly true with the emergence of a “supply chain mindset” as production processes become more international.

In this latest chapter, Jacques Roy (HEC Montréal, Professor of Logistics and Operations Management), examines the role of Canada’s transportation infrastructure in moving goods in and out of the country by four key transportation modes: road, rail, sea and air.

Overall, he finds that Canada’s transportation and logistics networks perform reasonably well compared with other countries. But he identifies several areas for improvement, namely for:

- roads: domestic congestion;

- rail: capacity constraints;

- sea: container port competitiveness; and

- air: cargo capacity, competitiveness and airport landing fees.

Roy points out that the countries that lead the global logistics performance rankings have all invested heavily in major hubs to connect various transportation modes efficiently. As the new federal government looks to increase infrastructure spending, he urges them to take advantage of the opportunity to enhance Canada’s trade-related infrastructure to support our trade, and thus our longer-term prosperity.

Canada’s shifting trade patterns by transportation mode

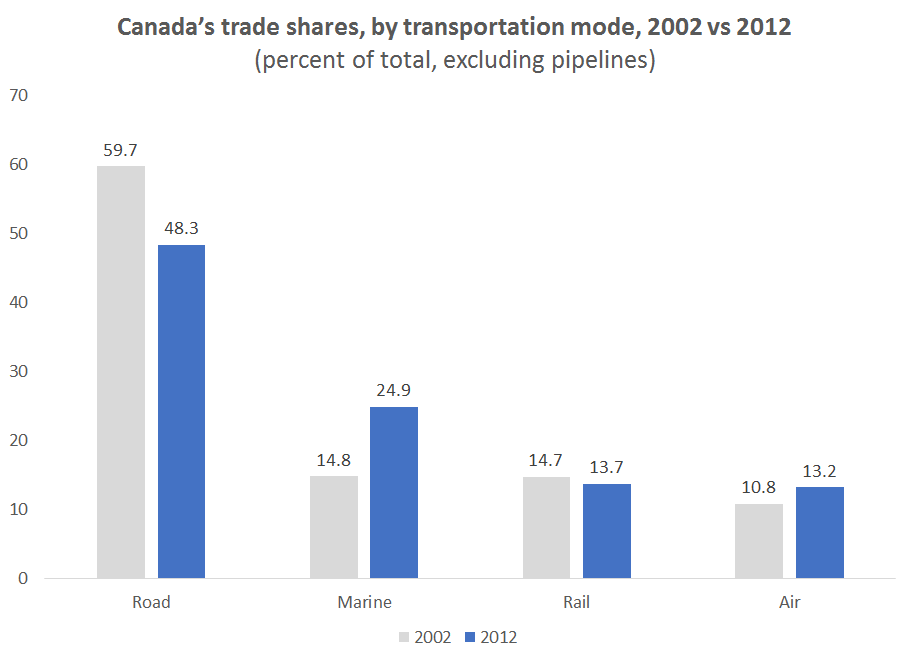

The chapter finds that, over the past decade, Canada’s goods trade has become far more reliant on marine transportation and less reliant on roads — although roads remain the most common mode by a wide margin:

The author suggests two key drivers of these trends.

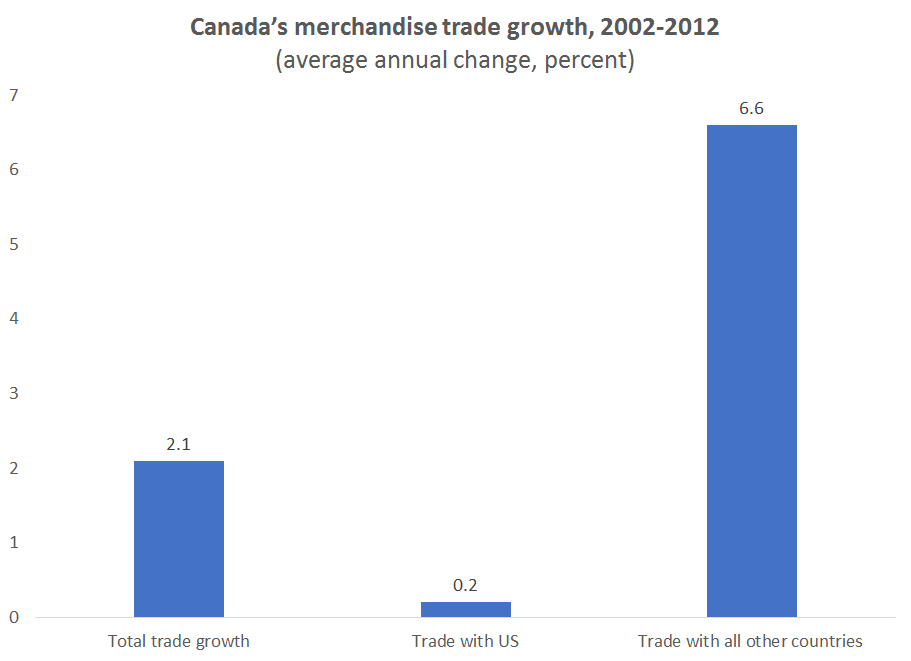

Driver 1: Canadian trade has stagnated with US, but grew with rest of world over the past decade.

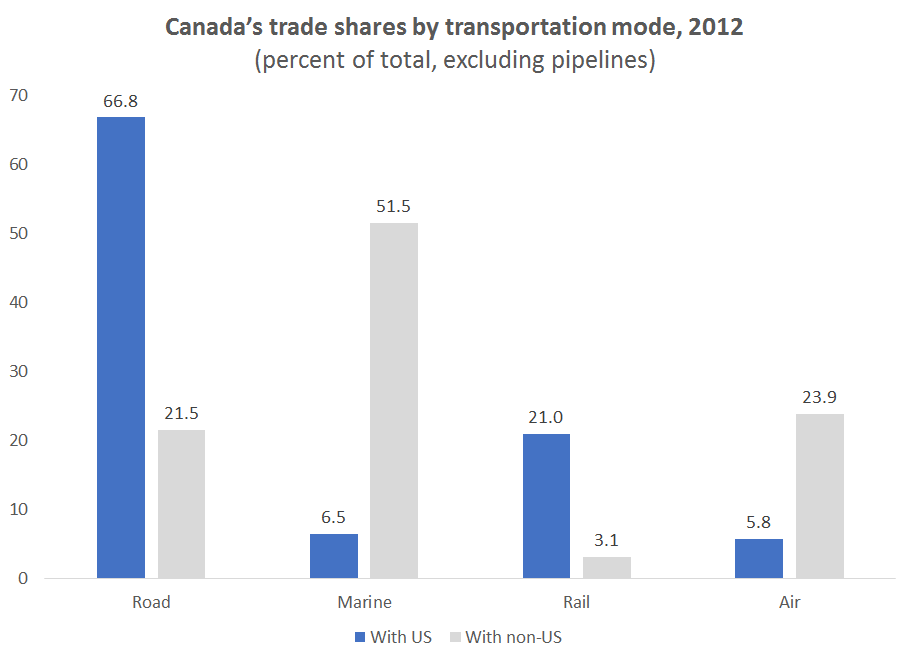

As a result of this differential performance, the share of Canada’s overall merchandise trade conducted with the US shrank from 76% in 2002 to 63% in 2012. These regional shifts matter for transportation because Canadian trade with the US relies heavily on roads (and, to a lesser extent, rail and pipelines), whereas Canadian trade with the rest of the world relies much more — and increasingly — on marine and air modes (figure below). Air is the dominant mode used for trade with Western Europe, while sea is primarily used for trade with Asia.

As a result of this differential performance, the share of Canada’s overall merchandise trade conducted with the US shrank from 76% in 2002 to 63% in 2012. These regional shifts matter for transportation because Canadian trade with the US relies heavily on roads (and, to a lesser extent, rail and pipelines), whereas Canadian trade with the rest of the world relies much more — and increasingly — on marine and air modes (figure below). Air is the dominant mode used for trade with Western Europe, while sea is primarily used for trade with Asia.

Driver 2: Increased use containerized freight in recent decades.

Driver 2: Increased use containerized freight in recent decades.

The value of Canada’s trade moved by sea nearly doubled between 2002 and 2012. This is largely due to increased containerized freight, which has been a major development in marine (and other) transportation modes in recent decades. Containerization allows for standardized sizes and easier intermodal transportation changes, including the ability to transfer containers seamlessly from ships to rail or trucks. This opens up more possible routes between the origin and final destination.

Canada’s biggest increases in marine traffic were on the country’s West Coast at the ports of Vancouver and Prince Rupert (the latter only started handling containers in 2007), which likely relates to increased trade with Asia, particularly China.

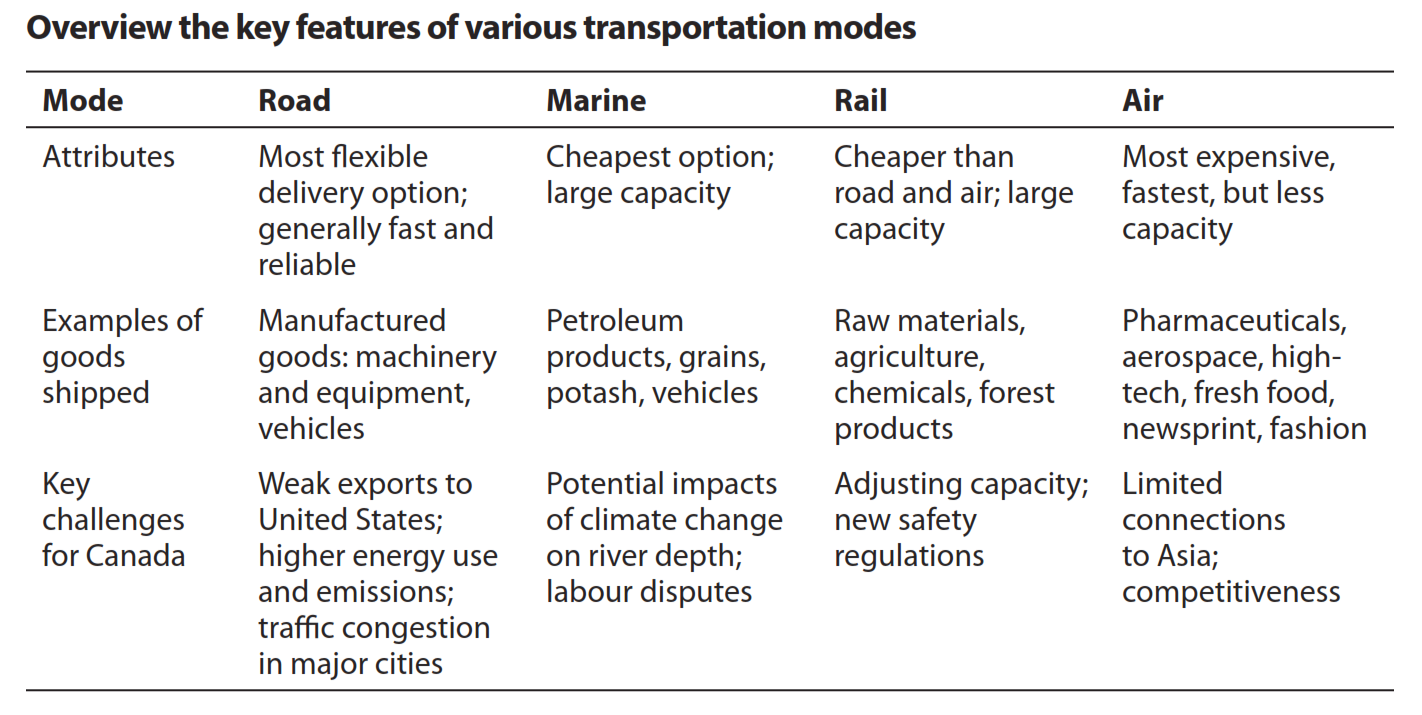

The chapter describes some considerations and trade-offs that firms face when shipping goods in and out of Canada. Roy provides an overview of each transportation mode and some of the emerging issues — this table gives a quick summary:

Policy recommendations

Policy recommendations

This chapter includes the following five policy recommendations:

1. Further Canada’s Gateway and Trade Corridor initiatives

As other countries invest heavily in their trade-related infrastructure, the Canadian government is on the right track with its Gateway and Trade Corridor programs, but these initiatives should be taken further. The Ontario-Quebec Continental Gateway initiative, in particular, has not yet fully delivered on its promises. A coherent plan to develop logistics clusters should be an integral part of the gateway program.

2. Plan continentally

There is a strong case for adopting a continental, North American approach — rather than simply focusing on Canada’s international border on its own — when planning transportation systems and infrastructure, as well as a potential security perimeter. Such an approach could, for instance, include simpler and smoother customs clearances with the US and Mexico.

3. Relieve domestic road congestion

Through its infrastructure programs, the federal government should assist provincial and municipal governments to repair roads and improve the fluidity of road travel. Interestingly, congestion at international border crossings no longer seems to be a major issue, but road congestion in large urban areas has become a major concern for shippers across the country. Goods in Canada can travel long distances by truck before reaching exit points at ports and border crossings. Road congestion adds to the cost of imports and exports and negatively affects the competitiveness of all industries moving products across major urban areas.

One potential policy response is to adopt congestion prices in some major cities (as advocated by Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission). However, Roy cautions that such a move is only one piece of a larger strategy that should be complemented by major investments in public transit. An additional part of the overall strategy that might require less up-front money would be to better harmonize road transportation regulations between provinces.

4. Encourage the use of information technology

Canada lags behind other countries — especially the US — in adopting new information technologies for logistics and supply chain applications. Policymakers, therefore, should examine the use of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and new technologies to facilitate transportation, which could help alleviate the road congestion issue and lower the cost of complying with various customs regulations.

5. Improve data collection

Canada needs to collect more and better data on its trade flows. In particular, Transport Canada should collect more data on the performance of ports, airports (including working with Statistics Canada to collect adequate air cargo data), bridges and other entry points. Canada’s transportation, trade and supply chain performance — and by implication its broader economic performance — cannot be improved if it isn’t measured accurately.

Conclusions

The competitiveness of Canada’s global supply chains and the reliability and efficiency of its transportation infrastructure go hand in hand. Over the past decade, a greater share of Canada’s merchandise trade has been transported by sea and air, and relatively less by roads and rail. This is due, in part, to changing regional patterns of Canada’s trade away from the US to other countries, as well as increased use of containers to ship goods.

Nonetheless, although roads have lost significant trade share over this period, they remain the most commonly used transportation mode for Canadian trade by a wide margin. Here, international border crossings no long seem to be a major concern for Canadian businesses. Instead, the bigger outstanding issues are Canada’s weak trade performance with the US, and domestic road congestion in major cities (such as Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver), which causes delays and additional costs for Canadian traders.

For its part, Canada’s rail system has faced capacity constraints and service issues, as well as safety concerns and regulatory reviews after the tragic accident in Lac-Mégantic in 2013.

Canadian ports and airports have become bigger conduits of international trade over the past decade, and recently concluded trade deals (CETA with the European Union and the TPP with 11 other Pacific Rim countries), if implemented, could reinforce these trends.

Canadian ports are generally well-equipped to handle bulk products, but the competitiveness of container ports is more fragile. Recent challenges include labour disputes, in both Canada and the US, reduced rail capacity in the winter to transport containers further inland to their final destinations, and the longer-term concern over climate change, which could reduce river depth and handling capacity along the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

A perennial challenge for Canada’s air cargo is its limited market size. This limits freighter capacity and makes it hard to compete on costs relative to US alternatives, which increasingly have been used to transport Canada’s aerospace exports (a phenomenon called “international leakage”). Canada’s competitive disadvantage is exacerbated by relatively high taxes and landing fees.

Compared with other countries, Canada generally has a competitive transportation infrastructure and overall good logistics performance, but more could be done to improve several key areas outlined above.

As the new federal government looks to increase infrastructure spending, it should adopt a long-term view and take advantage of the opportunity to enhance Canada’s trade-related infrastructure to support the country’s international trade and longer-term prosperity.

I encourage you to read the full chapter here, which is part of the IRPP’s forthcoming Canadian trade policy volume.