In Maximum Canada: Why 35 Million Canadians Are Not Enough, Doug Saunders provides a more sophisticated and nuanced discussion of the advantages of large-scale immigration and a larger population than others, such as the Advisory Council on Economic Growth and the Century Initiative. The essential argument, however, remains the same: Canada is too small a society and economy to attract and retain the most talented, pay for needed investments in infrastructure and public services, and address the aging of our population.

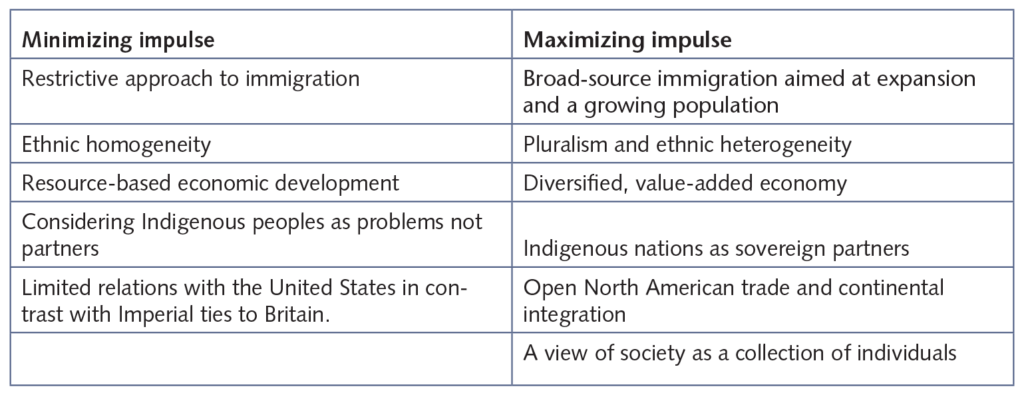

He effectively contrasts what he calls the “minimizing impulse” of a more defensive and inward-looking Canada prior to the 1960s with contemporary Canada, which is more open to the world in terms of population growth and of a diversified economy.

His historical overview reminds readers of the original “culture of accommodation” between Indigenous peoples and early French and British settlers, noting how this relationship broke down during the 19th century as Indigenous lands were “settled.”

He contrasts the rapid population growth of the United States, and the resulting economic development, with relative stagnation in Canada, due to a history of more restrictive immigration (and significant emigration) and to emphasis on trade with Britain over our southern neighbours.

Saunders highlights the Laurier government as the one exception, with its emphasis on large-scale immigration (400,000 in 1913) to foster development and industrialization. Following Laurier, Canada reverted to its minimizing impulse, although Saunders seems to ignore the impact of two world wars and the Depression, when immigration essentially stopped.

He notes the various factors after the Second World War that led to the more open, diverse and dynamic Canada of the 1960s. Some historians will contest his interpretation of Canada’s development, but his ideas provide a useful framework for understanding the extent and nature of changes in that decade.

The following table compares the minimizing and maximizing impulses. It oversimplifies the ethnic homogeneity/heterogeneity dichotomy, given Canada’s original Indigenous, French and British diversity, but it does reflect the country’s immigration priorities, save for during the Laurier period.

But beyond his historical account, how valid are Saunders’ substantive arguments for a large increase in population, through both immigration and births?

It is hard to argue against the proposition that a larger population, concentrated in our urban centres, would mean fewer Canadians having to leave Canada to pursue opportunities abroad. The need to address the problems of an aging population through immigration and higher rates of fertility is supported by demographic analysis. If globalization is truly at risk, a larger domestic market would help insulate Canada from the negative impacts of the loss of international markets. A denser population should also reduce per capita infrastructure costs and per capita environmental impacts.

The contention that a larger population would provide additional resources for defence and security, and a greater ability “to go it alone,” is unconvincing, given other more pressing needs caused by an increased population. It is also unclear that a larger population will mean significantly larger audiences for Canadian culture, given how cultural producers and consumers, at least in English Canada, are struggling with the impact of streaming services and social media.

Some of the assumptions underlying Saunders’ central arguments are questionable.

While worries about increased protectionism are understandable in the current context, it is premature to conclude how widespread the impact may be. After all, Britain is desperate to maintain access to markets while it negotiates Brexit; the Trump administration’s antitrade talk may be more bluster than substance; and the underlying capitalist dynamics of cost reduction, increased productivity, supply chains and growth are unlikely to turn the clock back to more autarchic economies.

A larger Canadian population will always be dwarfed by the US population, and thus the same fundamental factors that attract talented and ambitious Canadians to seek opportunities abroad will likely continue.

A more fundamental blind spot is his unstated assumption that ongoing developments in automation and artificial intelligence will not result in major changes to labour market needs and employment. While the pace and exact nature of change may be uncertain, the direction is clear, as we have already seen in reduced employment in manufacturing. The impact of artificial intelligence on services may form the next wave. Will previous patterns of “creative destruction” be more destructive than creative? Will a larger workforce really be needed to support an increasingly older population?

Saunders is silent on the reaction of Indigenous peoples and Quebecers to a large increase in Canada’s population, one largely fuelled by immigration and thus likely to decrease their relative political weight. This oversight is counterbalanced, however, by a serious analysis of some of the challenges (risks) of large immigration increases. Saunders correctly identifies ongoing employment issues such as more precarious employment and poorer economic outcomes among immigrants, as well as problems new Canadians experience in having their professional credentials recognized. He focuses on single-home ownership as a successful indicator of integration, while arguing at the same time for greater housing density and thus fewer single-family dwellings. He correctly references infrastructure and political issues that cause conflict between the denser urban cores and the suburbs. He provides a balanced discussion of the risks of possible political backlash, noting the need for ongoing attention and investments to minimize these risks.

He is also courageous in stating where the growth will occur, naming the cities of greatest growth and thus of the biggest need for investments: the Greater Toronto and Hamilton areas, the Calgary-Edmonton corridor, the Greater Montreal Area and some university cities such as Kitchener-Waterloo.

Moreover, in examining the risks of maximum growth, he makes clear that significant investments will be needed to address them, arguing that unless Canadians are willing to make these investments — “in education, urban and transportation infrastructure and reforms in housing and zoning, social benefits, tax, small business and family policies” — a “maximum” Canada will fail to deliver the potential benefits it promises. In delineating these concerns, he makes a major contribution, as other advocates have been relatively silent on the risks and on the investments needed to address them successfully.

While I remain skeptical of a “maximum” Canada, Saunders’ book is required reading for anyone interested in Canadian demographics and the challenges and choices facing our country.

Photo: Shutterstock, by hobbit.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.